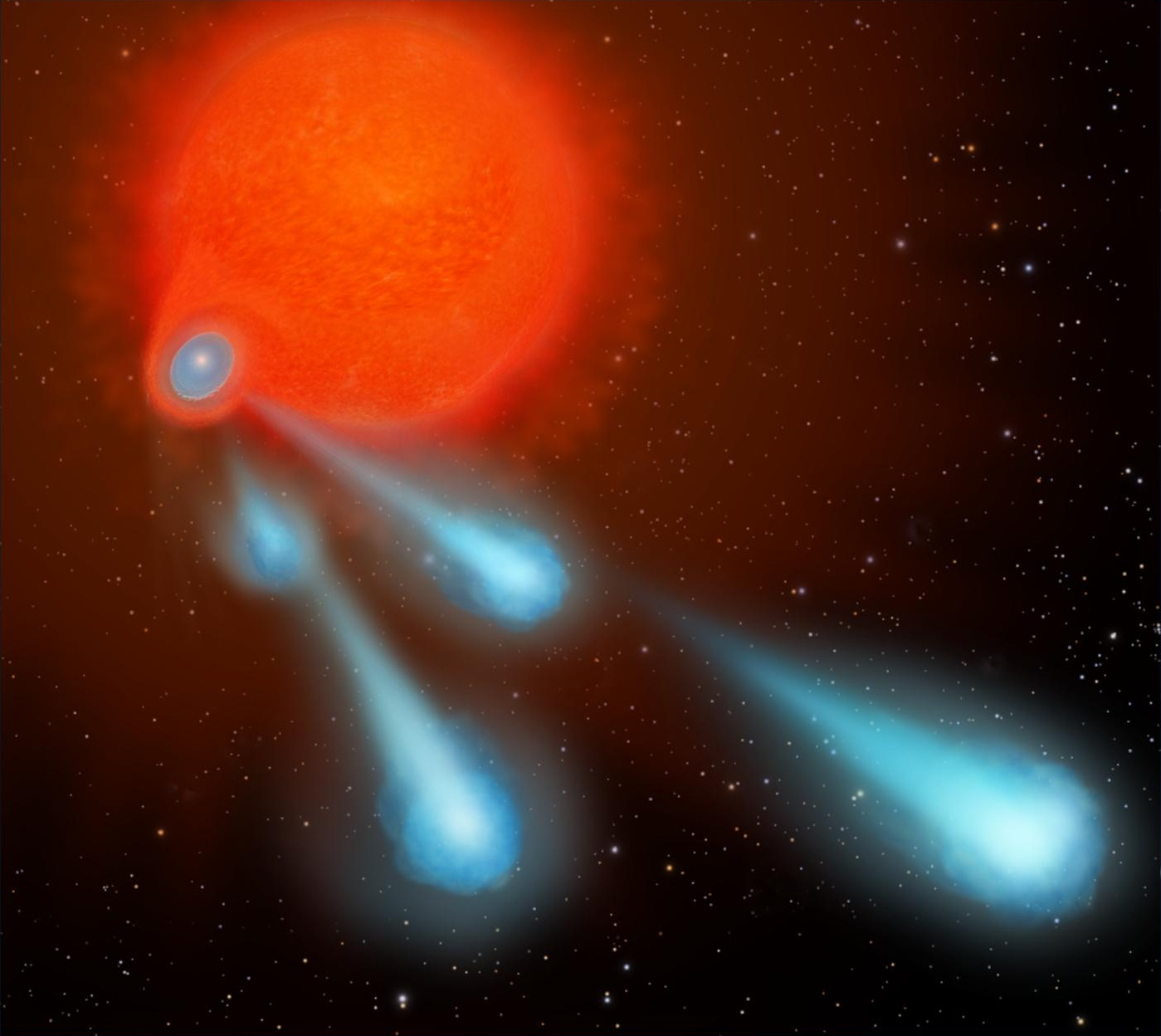

The fireballs present a puzzle to astronomers because the ejected material could not have been shot out by the host star, called V Hydrae. The star is a bloated red giant, residing 1,200 light-years away, which has probably shed at least half of its mass into space during its death throes. Red giants are dying stars in the late stages of life that are exhausting their nuclear fuel that makes them shine. They have expanded in size and are shedding their outer layers into space.

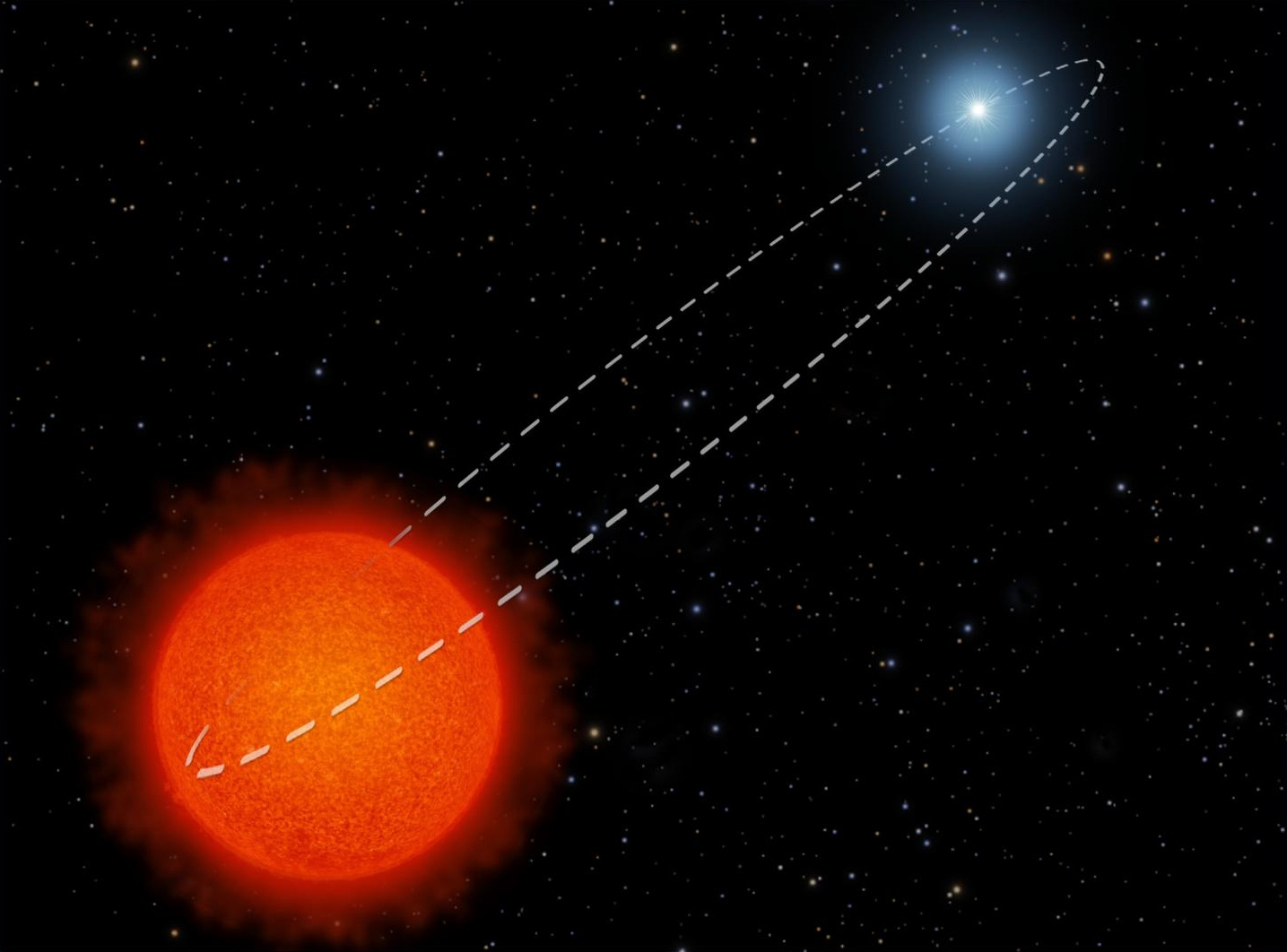

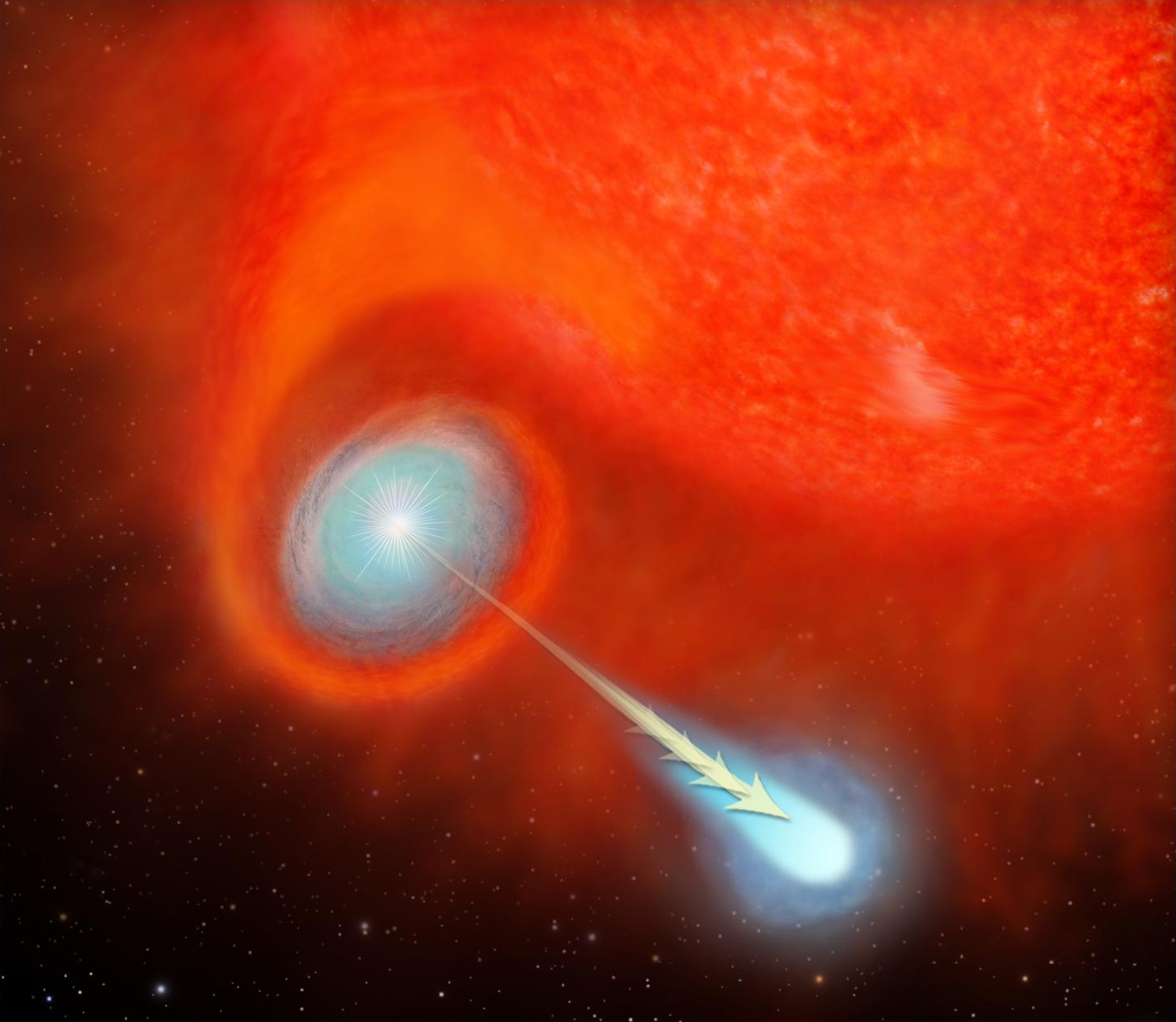

The current best explanation suggests the plasma balls were launched by an unseen companion star. According to this theory, the companion would have to be in an elliptical orbit that carries it close to the red giant’s puffed-up atmosphere every 8.5 years. As the companion enters the bloated star’s outer atmosphere, it gobbles up material. This material then settles into a disc around the companion, and serves as the launching pad for blobs of plasma, which travel at roughly a half-million miles per hour.

This star system could be the archetype to explain a dazzling variety of glowing shapes uncovered by Hubble that are seen around dying stars, called planetary nebulae, researchers say. A planetary nebula is an expanding shell of glowing gas expelled by a star late in its life.

Hubble observations over the past two decades have revealed an enormous complexity and diversity of structure in planetary nebulae. The telescope’s high resolution captured knots of material in the glowing gas clouds surrounding the dying stars. Astronomers speculated that these knots were actually jets ejected by discs of material around companion stars that were not visible in the Hubble images. Most stars in our Milky Way galaxy are members of binary systems. But the details of how these jets were produced remained a mystery.

“We want to identify the process that causes these amazing transformations from a puffed-up red giant to a beautiful, glowing planetary nebula,” Sahai said. “These dramatic changes occur over roughly 200 to 1,000 years, which is the blink of an eye in cosmic time.”

Sahai’s team used Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (STIS) to conduct observations of V Hydrae and its surrounding region over an 11-year period, first from 2002 to 2004, and then from 2011 to 2013. Spectroscopy decodes light from an object, revealing information on its velocity, temperature, location, and motion.

The blobs expand and cool as they move farther away, and are then not detectable in visible light. But observations taken at longer sub-millimetre wavelengths in 2004, by the Submillimetre Array in Hawaii, revealed fuzzy, knotty structures that may be blobs launched 400 years ago, the researchers said.

Based on the observations, Sahai and his colleagues Mark Morris of the University of California, Los Angeles, and Samantha Scibelli of the State University of New York at Stony Brook developed a model of a companion star with an accretion disc to explain the ejection process.

“This model provides the most plausible explanation because we know that the engines that produce jets are accretion discs,” Sahai explained. “Red giants don’t have accretion discs, but many most likely have companion stars, which presumably have lower masses because they are evolving more slowly. The model we propose can help explain the presence of bipolar planetary nebulae, the presence of knotty jet-like structures in many of these objects, and even multipolar planetary nebulae. We think this model has very wide applicability.”

Astronomers have noted that V Hydrae is obscured every 17 years, as if something is blocking its light. Sahai and his colleagues suggest that due to the back-and-forth wobble of the jet direction, the blobs alternate between passing behind and in front of V Hydrae. When a blob passes in front of V Hydrae, it shields the red giant from view.

“This accretion disc engine is very stable because it has been able to launch these structures for hundreds of years without falling apart,” Sahai said. “In many of these systems, the gravitational attraction can cause the companion to actually spiral into the core of the red giant star. Eventually, though, the orbit of V Hydrae’s companion will continue to decay because it is losing energy in this frictional interaction. However, we do not know the ultimate fate of this companion.”

The team hopes to use Hubble to conduct further observations of the V Hydrae system, including the most recent blob ejected in 2011. The astronomers also plan to use the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile to study blobs launched over the past few hundred years that are now too cool to be detected with Hubble.

The team’s results recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal.