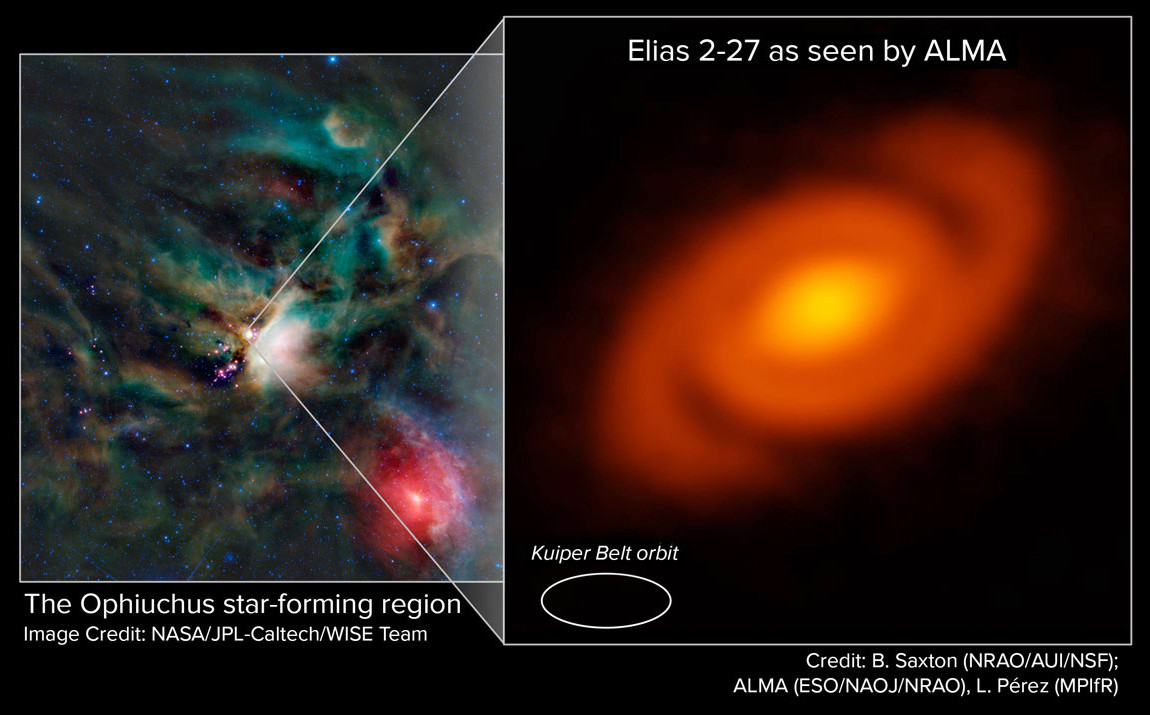

“These observations are the first direct evidence for density waves in a protoplanetary disc,” said Laura Pérez, an astronomer and Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellow with the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, and lead author on a paper published in the journal Science.

Previously, astronomers noted compelling spiral features on the surfaces of protoplanetary discs, but it was unknown if these same spiral patterns also emerged deep within the disc where planet formation takes place. ALMA, for the first time, was able to peer deep into the mid-plane of a disc and discover the clear signature of spiral density waves.

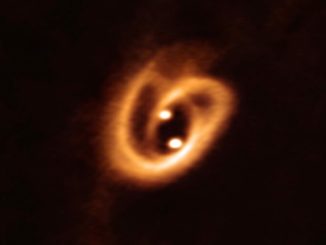

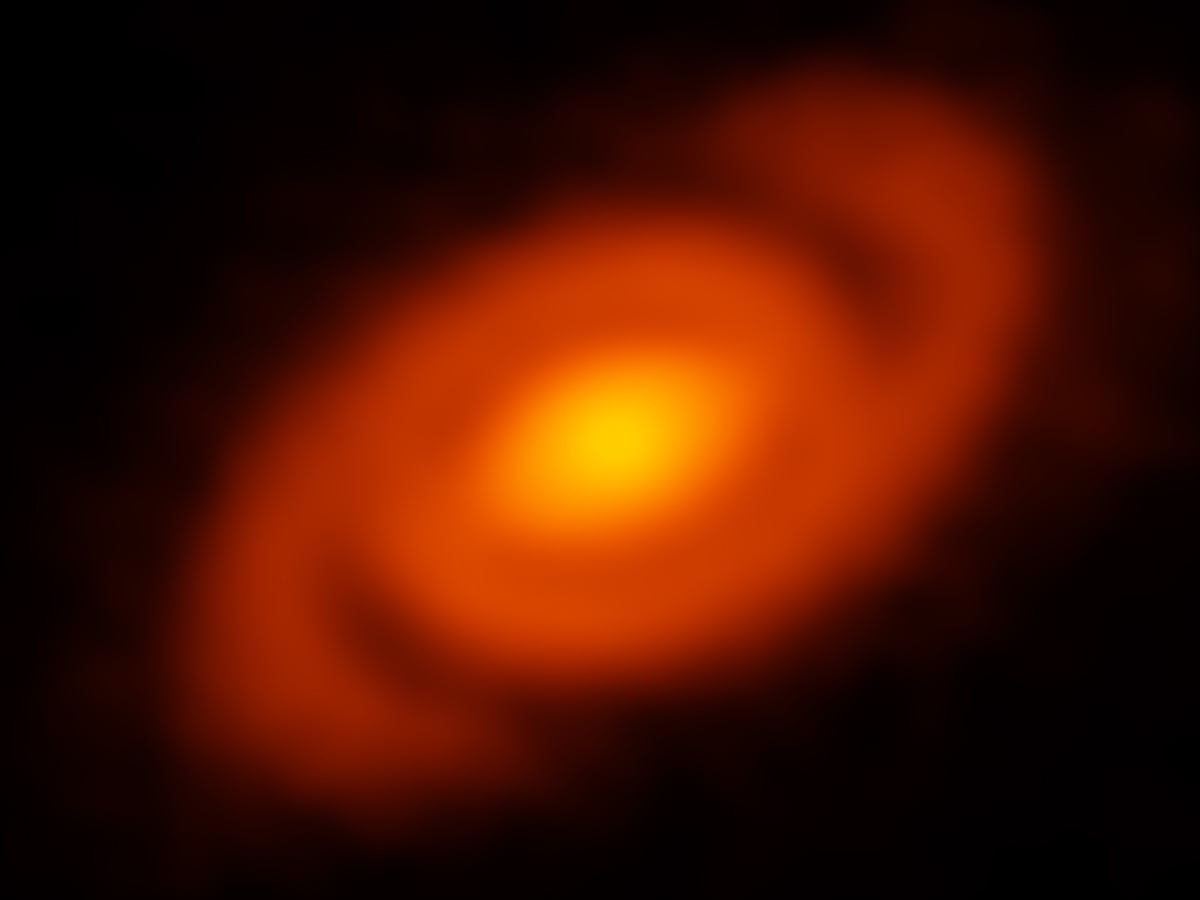

Nearest to the star, ALMA found a familiar flattened disc of dust, which extends past what would be the orbit of Neptune in our own solar system. Beyond that point, ALMA detected a narrow band with significantly less dust, which may be indicative of a planet in formation. Springing from the outer edge of this gap are two sweeping spiral arms that extend more than 10 billion kilometres away from their host star.

Elias 2-27 is located approximately 450 light-years from Earth in the Ophiuchus star-forming complex. Even though it contains only about half the mass of our Sun, this star has an unusually massive protoplanetary disc. The star is estimated to be at least one million years old and still encased in its parent molecular cloud, obscuring it from optical telescopes.

“There are still questions of how these features form. Perhaps they are the result of a newly forged planet interacting with the protoplanetary disc or simply gravitational instabilities driven by the shear mass of the disc,” said Andrea Isella, an astronomer at Rice University in Houston, Texas, and co-author of the paper.

“Fortunately, the power of ALMA will be used in the future to answer this puzzle,” concludes Pérez. “ALMA will further dissect this and other similar discs in an upcoming large program, helping astronomers understand the seemingly chaotic forces that eventually give rise to stable planetary systems like our own.”