The team used HARPS, along with other instruments, to look for the signatures of giant planets on short-period orbits, hoping to see the tell-tale “wobble” of a star caused by the presence of a massive object in a close orbit, a kind of planet known as a hot Jupiters. This hot Jupiter signature has now been found for a total of three stars in the cluster alongside earlier evidence for several other planets.

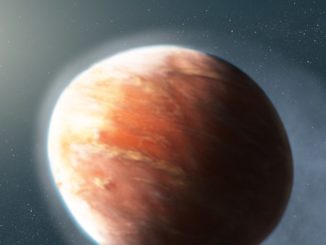

A hot Jupiter is a giant exoplanet with a mass of more than about a third of Jupiter’s mass. They are “hot” because they are orbiting close to their parent stars, as indicated by an orbital period (their “year”) that is less than ten days in duration. That is very different from the Jupiter we are familiar with in our own Solar System, which has a year lasting around 12 Earth-years and is much colder than the Earth.

“We want to use an open star cluster as laboratory to explore the properties of exoplanets and theories of planet formation”, explains Roberto Saglia. “Here we have not only many stars possibly hosting planets, but also a dense environment, in which they must have formed.”

The study found that hot Jupiters are more common around stars in Messier 67 than is the case for stars outside of clusters. “This is really a striking result,” marvels Anna Brucalassi, who carried out the analysis. “The new results mean that there are hot Jupiters around some 5 percent of the Messier 67 stars studied — far more than in comparable studies of stars not in clusters, where the rate is more like 1 percent.”

Astronomers think it highly unlikely that these exotic giants actually formed where we now find them, as conditions so close to the parent star would not initially have been suitable for the formation of Jupiter-like planets. Rather, it is thought that they formed further out, as Jupiter probably did, and then moved closer to the parent star. What were once distant, cold, giant planets are now a good deal hotter. The question then is: what caused them to migrate inwards towards the star?

There are a number of possible answers to that question, but the authors conclude that this is most likely the result of close encounters with neighbouring stars, or even with the planets in neighbouring solar systems, and that the immediate environment around a solar system can have a significant impact on how it evolves.

In a cluster like Messier 67, where stars are much closer together than the average, such encounters would be much more common, which would explain the larger numbers of hot Jupiters found there.

Co-author and co-lead Luca Pasquini from ESO looks back on the remarkable recent history of studying planets in clusters: “No hot Jupiters at all had been detected in open clusters until a few years ago. In three years the paradigm has shifted from a total absence of such planets — to an excess!”