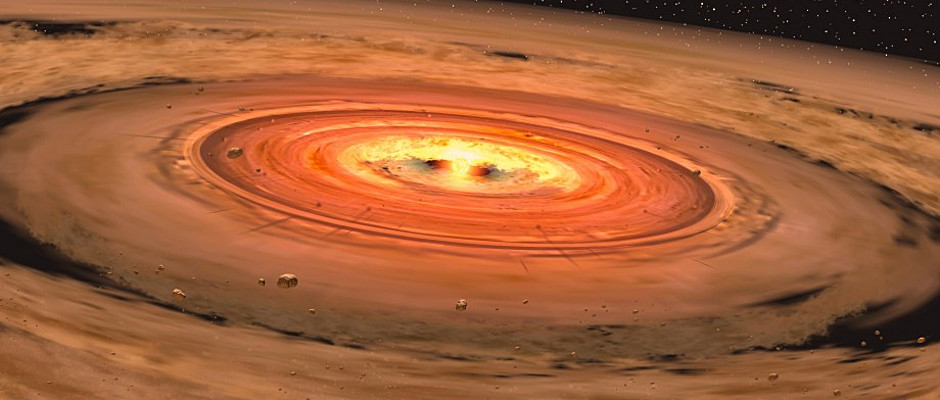

“We think the Earth and all the other planets formed from discs like these so it is fascinating to see a potential new solar system evolving,” said the lead researcher Dr. Simon Murphy, from the ANU Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

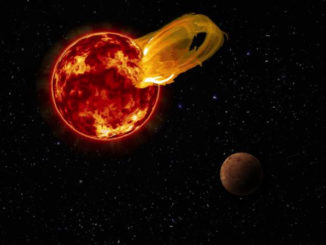

“However, other stars of this age usually don’t have discs any more. The red dwarf discs seem to live longer than those of hotter stars like the Sun. We don’t understand why,” said Dr. Murphy.

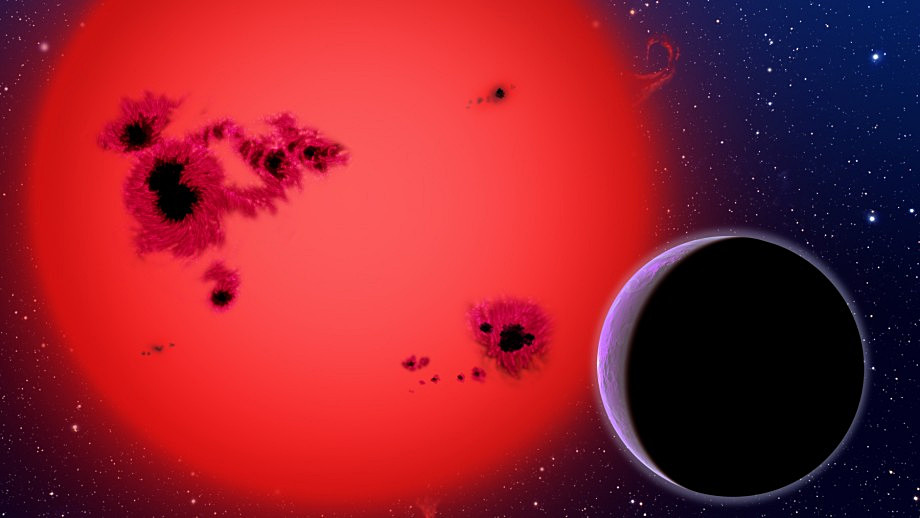

The red dwarfs may also host planets that have already formed from the dusty discs, Dr. Murphy added. “I think a lot of telescopes will be turned toward them in the next few years to look for planets,” he said.

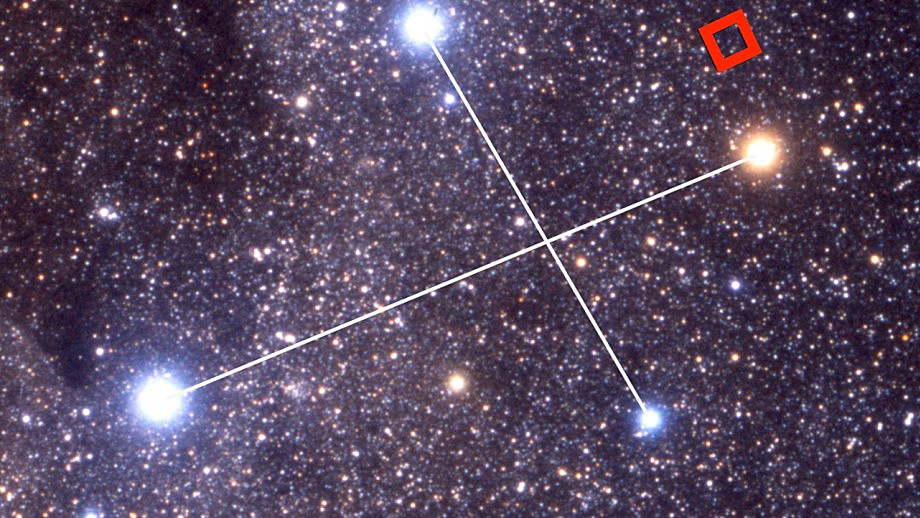

The giveaway that the red dwarfs had discs around them was an unusual glow in the infrared spectrum of the stars.

Although the discs were not observed directly, Dr. Murphy said such close red dwarfs offered a good chance of catching a rare direct glimpse of a disc, or even a planet, by employing specialised telescopes. “Because they are fainter than other stars and there is not as much glare, young red dwarfs are ideal places to directly pick out recently formed planets,” he said.

“Most of these objects lie in the southern sky and thus are best accessed by telescopes in the Southern Hemisphere, including those operated by ANU and Australia more broadly,” added Professor Lawson.

The research is published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.