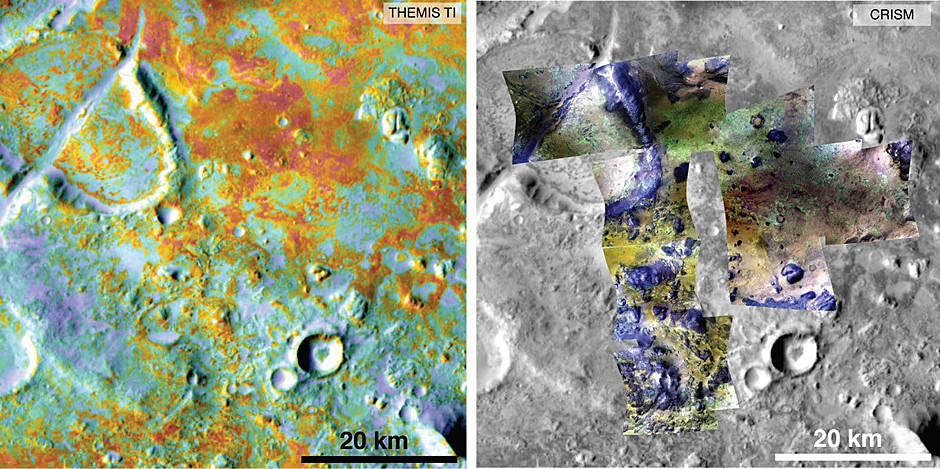

Carbon dioxide makes up most of the Martian atmosphere. That gas can be pulled out of the air and sequestered or pulled into the ground by chemical reactions with rocks to form carbonate minerals. Years before the series of successful Mars missions, many scientists expected to find large Martian deposits of carbonates holding much of the carbon from the planet’s original atmosphere. Instead, these missions have found low concentrations of carbonate distributed widely, and only a few concentrated deposits. By far the largest known carbonate-rich deposit on Mars covers an area at least the size of Delaware, and maybe as large as Arizona, in a region called Nili Fossae.

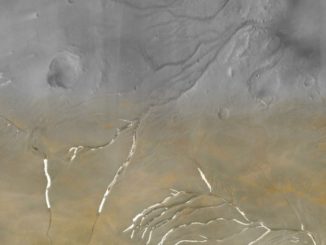

Christopher Edwards, a former Caltech researcher now with the U.S. Geological Survey in Flagstaff, Arizona, and Ehlmann reported the findings and analysis in a paper posted online by the journal Geology. Their estimate of how much carbon is locked into the Nili Fossae carbonate deposit uses observations from numerous Mars missions, including the Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES) on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor orbiter, the mineral-mapping Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) and two telescopic cameras on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) on NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter.

The modern Martian atmosphere is too tenuous for liquid water to persist on the surface. A denser atmosphere on ancient Mars could have kept water from immediately evaporating. It could also have allowed parts of the planet to be warm enough to keep liquid water from freezing. But if the atmosphere was once thicker, what happened to it? One possible explanation is that Mars did have a much denser atmosphere during its flowing-rivers period, and then lost most of it to outer space from the top of the atmosphere, rather than by sequestration in minerals.

“Maybe the atmosphere wasn’t so thick by the time of valley network formation,” Edwards said. “Instead of Mars that was wet and warm, maybe it was cold and wet with an atmosphere that had already thinned. How warm would it need to have been for the valleys to form? Not very. In most locations, you could have had snow and ice instead of rain. You just have to nudge above the freezing point to get water to thaw and flow occasionally, and that doesn’t require very much atmosphere.”

NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover mission has found evidence of ancient top-of-atmosphere loss, based on the modern Mars atmosphere’s ratio of heavier carbon to lighter carbon. Uncertainty remains about how much of that loss occurred before the period of valley formation; much may have happened earlier. NASA’s MAVEN orbiter, examining the outer atmosphere of Mars since late 2014, may help reduce that uncertainty.