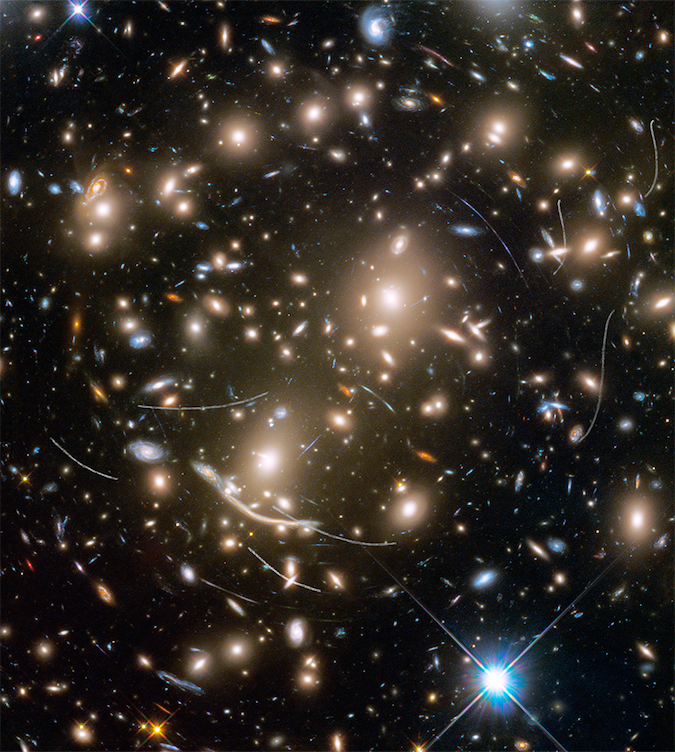

Like rude relatives who jump in front your vacation snapshots of landscapes, some of our solar system’s asteroids have photobombed deep images of the universe taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. These asteroids reside, on average, only about 160 million miles from Earth-right around the corner in astronomical terms. Yet they’ve horned their way into this picture of thousands of galaxies scattered across space and time at inconceivably farther distances.

This Hubble photo of a random patch of sky is part of a survey called Frontier Fields. The colorful image contains thousands of galaxies, including massive yellowish ellipticals and majestic blue spirals. Much smaller, fragmentary blue galaxies are sprinkled throughout the field. The reddest objects are most likely the farthest galaxies, whose light has been stretched into the red part of the spectrum by the expansion of space.

Intruding across the picture are asteroid trails that appear as curved or S-shaped streaks. Rather than leaving one long trail, the asteroids appear in multiple Hubble exposures that have been combined into one image. Of the 20 total asteroid sightings for this field, seven are unique objects. Of these seven asteroids, only two were earlier identified. The others were too faint to be seen previously.

The trails look curved due to an observational effect called parallax. As Hubble orbits around Earth, an asteroid will appear to move along an arc with respect to the vastly more distant background stars and galaxies.

This parallax effect is somewhat similar to the effect you see from a moving car, in which trees by the side of the road appear to be passing by much more rapidly than background objects at much larger distances. The motion of Earth around the Sun, and the motion of the asteroids along their orbits, are other contributing factors to the apparent skewing of asteroid paths.

All the asteroids were found manually, the majority by “blinking” consecutive exposures to capture apparent asteroid motion. Astronomers found a unique asteroid for every 10 to 20 hours of exposure time.

The Frontier Fields program is a collaboration among NASA’s Great Observatories and other telescopes to study six massive galaxy clusters and their effects. Using a different camera, pointing in a slightly different direction, Hubble photographed six so-called “parallel fields” at the same time it photographed the massive galaxy clusters. This maximized Hubble’s observational efficiency in doing deep space exposures. These parallel fields are similar in depth to the famous Hubble Deep Field, and include galaxies about four-billion times fainter than can be seen by the human eye.

This picture is of the parallel field for the galaxy cluster Abell 370. It was assembled from images taken in visible and infrared light. The field’s position on the sky is near the ecliptic, the plane of our solar system. This is the zone in which most asteroids reside, which is why Hubble astronomers saw so many crossings. Hubble deep-sky observations taken along a line-of-sight near the plane of our solar system commonly record asteroid trails.