The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, used data from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) XMM-Newton space observatory to reveal for the first time strong winds gusting at very high speeds from two mysterious sources of X-ray radiation. The discovery, published in the journal Nature, confirms that these sources conceal a compact object pulling in matter at extraordinarily high rates.

When observing the Universe at X-ray wavelengths, the celestial sky is dominated by two types of astronomical objects: supermassive black holes, sitting at the centres of large galaxies and ferociously devouring the material around them, and binary systems, consisting of a stellar remnant — a white dwarf, neutron star or black hole — feeding on gas from a companion star.

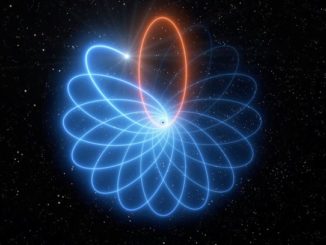

In both cases, the gas forms a swirling disc around the compact and very dense central object. Friction in the disc causes the gas to heat up and emit light at different wavelengths, with a peak in X-rays.

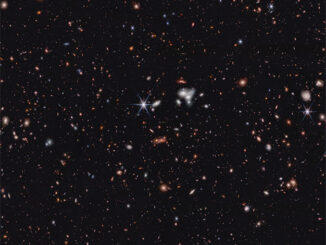

But an intermediate class of objects was discovered in the 1980s and is still not well understood. Ten to a hundred times brighter than ordinary X-ray binaries, these sources are nevertheless too faint to be linked to supermassive black holes, and in any case, are usually found far from the centre of their host galaxy.

“We think these so-called ‘ultra-luminous X-ray sources’ are special binary systems, sucking up gas at a much higher rate than an ordinary X-ray binary,” said Dr Ciro Pinto from Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, the paper’s lead author. “Some of these sources host highly magnetised neutron stars, while others might conceal the long-sought-after intermediate-mass black holes, which have masses around one thousand times the mass of the Sun. But in the majority of cases, the reason for their extreme behaviour is still unclear.”

In all three sources, the scientists were able to identify X-ray emission from gas in the outer portions of the disc surrounding the central compact object, slowly flowing towards it.

But two of the three sources — known as NGC 1313 X-1 and NGC 5408 X-1 — also show clear signs of X-rays being absorbed by gas that is streaming away from the central source at 70,000 kilometres per second — almost a quarter of the speed of light.

“This is the first time we’ve seen winds streaming away from ultra-luminous X-ray sources,” said Pinto. “And the very high speed of these outflows is telling us something about the nature of the compact objects in these sources, which are frantically devouring matter.”

While the hot gas is pulled inwards by the central object’s gravity, it also shines brightly, and the pressure exerted by the radiation pushes it outwards. This is a balancing act: the greater the mass, the faster it draws the surrounding gas; but this also causes the gas to heat up faster, emitting more light and increasing the pressure that blows the gas away.

Eddington’s calculation refers to an ideal case in which both the matter being accreted onto the central object and the radiation being emitted by it do so equally in all directions.

But the sources studied by Pinto and his collaborators are potentially being fed through a disc which has been puffed up due to internal pressures arising from the incredible rates of material passing through it. These thick discs can naturally exceed the Eddington limit and can even trap the radiation in a cone, making these sources appear brighter when we look straight at them. As the thick disc moves material further from the black hole’s gravitational grasp it also gives rise to very high-speed winds like the ones observed by the Cambridge researchers.

“By observing X-ray sources that are radiating beyond the Eddington limit, it is possible to study their accretion process in great detail, investigating by how much the limit can be exceeded and what exactly triggers the outflow of such powerful winds,” said Norbert Schartel, ESA XMM-Newton Project Scientist.

The nature of the compact objects hosted at the core of the two sources observed in this study is, however, still uncertain.

Based on the X-ray brightness, the scientists suspect that these mighty winds are driven from accretion flows onto either neutron stars or black holes, the latter with masses of several to a few dozen times that of the Sun.

To investigate further, the team is still scrutinising the data archive of XMM-Newton, searching for more sources of this type, and are also planning future observations, in X-rays as well as at optical and radio wavelengths.

“With a broader sample of sources and multi-wavelength observations, we hope to finally uncover the physical nature of these powerful, peculiar objects,” said Pinto.