There are two basic types of black holes known to scientists according to observations: supermassive black holes and stellar-mass black holes. It is generally believed that stellar-mass black holes are formed in the end of the evolution of massive stars, when stellar energy sources are exhausted, and the star collapses due to its own gravity. Theoretical calculations impose restrictions on their mass to the extent of 5—50 solar masses.

It’s less clear how supermassive black holes come to existence. Masses of these black holes sitting in the centres of most galaxies range between millions and billions of solar masses. Quasars, the active galactic nuclei, are supermassive black holes observed by astronomers at high redshift. It means that these giants existed in the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

Ivan Zolotukhin, who works at the Research Institute of Astrophysics and Planetology (Toulouse), said: “Astronomers look for black holes of intermediate mass, because no black hole that weighs a billion times more than the Sun could have been formed without them in just 700 million years.”

A small number means about hundred pieces per a galaxy similar to our Milky Way. They should fly somewhere high above the galaxy plane because, while merging, black holes acquire a huge impulse that sometimes can throw them out of the galaxy. About 10 years ago, the researchers were looking for such kind of holes (thousands of solar masses) among the heavy stellar-mass holes and the light supermassive ones, but nothing lighter than 500,000 solar masses has been found.

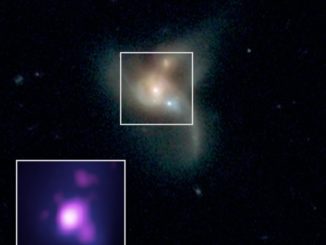

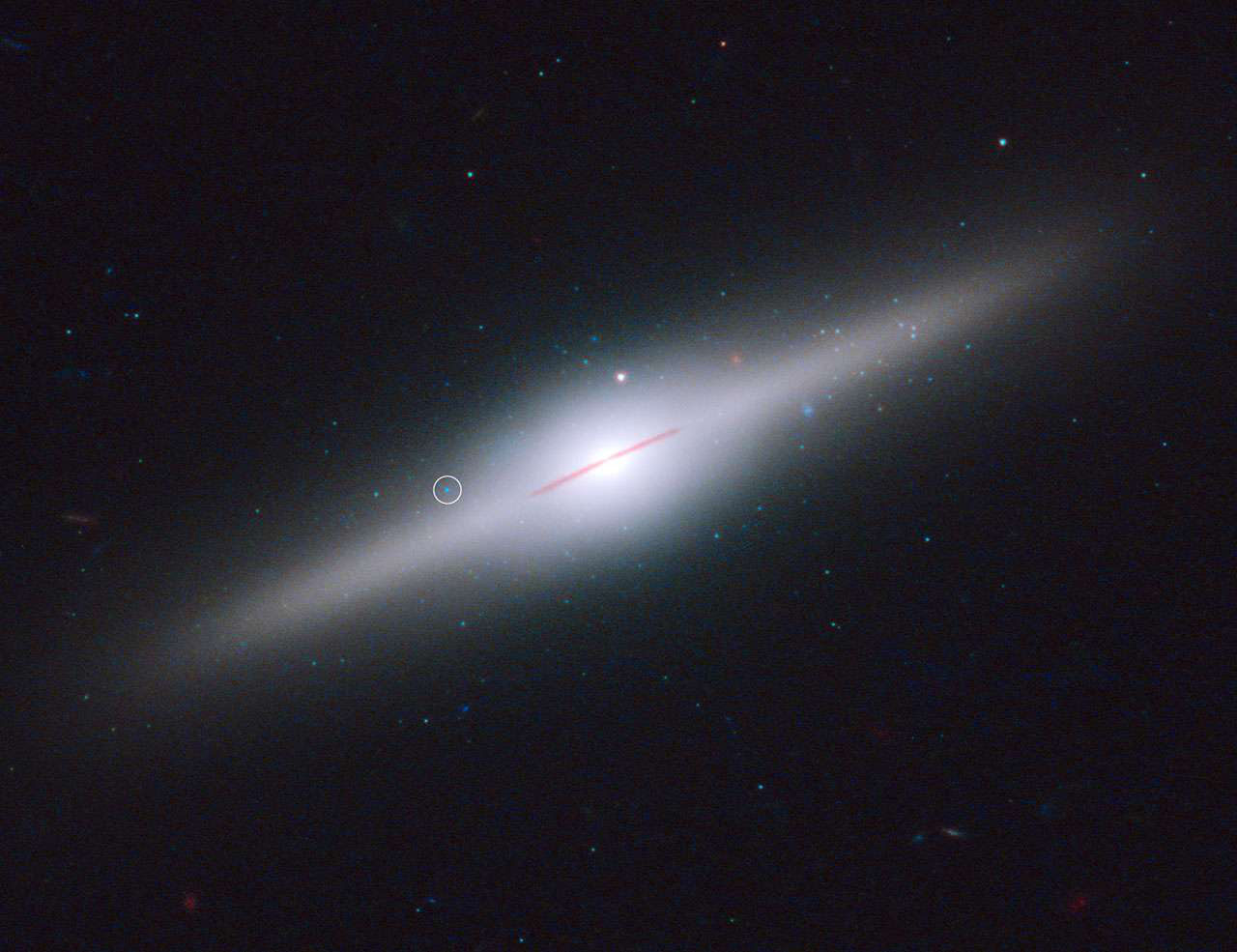

The paper was published in 2009 by astronomers from Toulouse, who in the course of a search for neutron stars in our galaxy accidentally found a bright X-ray source close to the galaxy, located at a distance of 100 megaparsecs (Mpc) from Earth. Luminosity evaluation showed that the mass of the object is about 10,000 solar masses. It is most likely that it shines due to the overflowing of matter into a black hole from a single star. A unique object called HLX-1 (hyper-luminous X-ray source 1) is now the only reliable candidate as the intermediate-mass black hole. Many astronomers were sure that this object is unique, and there won’t be any similar to this. At the same time they didn’t take into consideration that this object was found by chance, and in a catalog of sources covering only 1 percent of the sky.

“I supposed that such objects should appear much more often, and we have proposed a method of large scale search,” said Zolotukhin. The idea is to compare the objects from the wide-scale redshift survey of galaxies (e.g., Sloan Digital Sky Survey, SDSS) with the objects from a catalog of X-ray sources. “I suggested looking around galaxies for millions of X-ray objects with luminosity exceeding a certain value,” the author explained.

Having applied the developed algorithm to both catalogs, the astronomers were able to find 98 objects, among which at least 16 must be associated with their galaxies. “These are the best candidates for intermediate-mass black holes. We have shown for the first time that a new type of hypothetical intermediate mass black holes (with masses from 100 to 100,000 solar masses) not only exist, but also exist in a population. In other words, these objects are not unique, there are lots of them,” clarified the author of the paper just published in the Astrophysical Journal.

The methods of the Virtual Observatory were applied in the research, and all the conclusions were obtained exclusively with the use of publicly available data and, therefore, can be confirmed from any computer with Internet access.

Moreover, the authors used a new site to access the data of the XMM-Newton observatory. “The uniqueness of this web application is that for the first time in international fundamental science such a complicated project is made specifically for scientists by volunteers — highly skilled programmers, who, while working at the best IT companies in Russia, devoted their free time to this web page. They are Alexey Sergeev, Askar Timirgazin, and Maxim Chernyshov,” told Ivan Zolotukhin, “Many of my colleagues and I are still impressed by their work. The astronomers around the world can now enjoy the unique features of the site, and many discoveries can now be done directly online!” According to Zolotukhin, the current publication presents a series of studies based on this website. “It is important that thanks to simple and clear design scientists from other fields can now enjoy specific X-ray data,” said the scientist.

This study essentially opens up the possibility for the search of intermediate-mass black holes. Since the researchers suggested more than a dozen of such candidates, it is expected that in the years to come they will be reliably confirmed with optical spectroscopic observations. In the near future it is expected to search for them by the six-metre telescope of the Special Astrophysical Observatory (Russia) as well. “If there is at least one confirmation — it will be published in Nature, and astronomers immediately will rush to explore these 98 objects,” said the author of the work.

The candidates were found only in 2 percent of the sky, so astronomers hope to launch a Russian-German space telescope “Spektr-RG” in 2017. The researchers hope to discover hundreds of objects like HLX-1 through a deep X-ray view of the sky obtained by the means of this telescope.