Dr. Keith Bannister, CSIRO astronomer and first author of a paper released in Science, said the structures appear to be ‘lumps’ in the thin gas that lies between the stars in our galaxy.

“They could radically change ideas about this interstellar gas, which is the galaxy’s star recycling depot, housing material from old stars that will be refashioned into new ones,” Dr. Bannister said.

Dr. Bannister and his colleagues described breakthrough observations of one of these ‘lumps’ that have allowed them to make the first estimate of its shape.

The observations were made possible by an innovative new technique the scientists employed using CSIRO’s Compact Array telescope in eastern Australia.

Astronomers got the first hints of the mysterious objects 30 years ago when they saw radio waves from a bright, distant galaxy called a quasar varying wildly in strength.

They figured out this behaviour was the work of our galaxy’s invisible ‘atmosphere,’ a thin gas of electrically charged particles which fills the space between the stars.

“Lumps in this gas work like lenses, focusing and defocusing the radio waves, making them appear to strengthen and weaken over a period of days, weeks or months,” Dr. Bannister said.

These episodes were so hard to find that researchers had given up looking for them. But Dr. Bannister and his colleagues realised they could do it with CSIRO’s Compact Array.

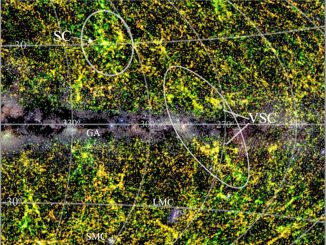

Pointing the telescope at a quasar called PKS 1939-315 in the constellation of Sagittarius, they saw a lensing event that went on for a year.

Until now they knew nothing about their shape, however, the team has shown this lens could not be a solid lump or shaped like a bent sheet.

“We could be looking at a flat sheet, edge on,” CSIRO team member Dr. Cormac Reynolds said.

“Or we might be looking down the barrel of a hollow cylinder like a noodle, or at a spherical shell like a hazelnut.”

Getting more observations will “definitely sort out the geometry,” he said.

While the lensing event went on, Dr. Bannister’s team observed it with other radio and optical telescopes.

The optical light from the quasar didn’t vary while the radio lensing was taking place. This is important, Dr. Bannister said, because it means earlier optical surveys that looked for dark lumps in space couldn’t have found the one his team has detected.

So what can these lenses be? One suggestion is cold clouds of gas that stay pulled together by the force of their own gravity. That model, worked through in detail, implies the clouds must make up a substantial fraction of the mass of our galaxy.

Nobody knows how the invisible lenses could form.

“But these structures are real, and our observations are a big step forward in determining their size and shape,” Dr. Bannister said.