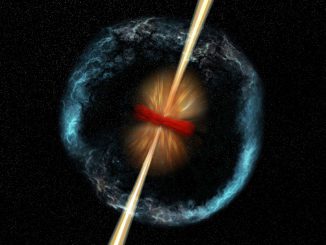

By poring over 650 hours of archival data from the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Green Bank Telescope (GBT), a team of astronomers uncovered the most detailed record ever of an FRB. Their research indicates that the burst originated inside a highly magnetised region of space, possibly linking it to a recent supernova or the interior of an active star-forming nebula.

“We now know that the energy from this FRB passed through a dense, magnetised region shortly after it formed. This significantly narrows down the source’s environment and type of event that triggered the burst,” said Kiyoshi Masui, an astronomer with the University of British Columbia and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research.

Lasting only a fraction of a second yet packing a phenomenal amount of energy, FRBs are brief radio flashes of unknown origin that appear to come from random directions on the sky. Though only a handful have been documented previously, astronomers believe that the observable universe is rocked by thousands of these events each day.

Mining data to find elusive nugget

The astronomers found the newly identified FRB, dubbed FRB 110523, by using highly specialised software developed by Masui and his colleague Jonathan Sievers from the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa.

The recorded data — a total of 40 terabytes — created a substantial analysis challenge, which was made even more difficult because the otherwise short, sharp signal of an FRB becomes “smeared out” in frequency by its journey through space.

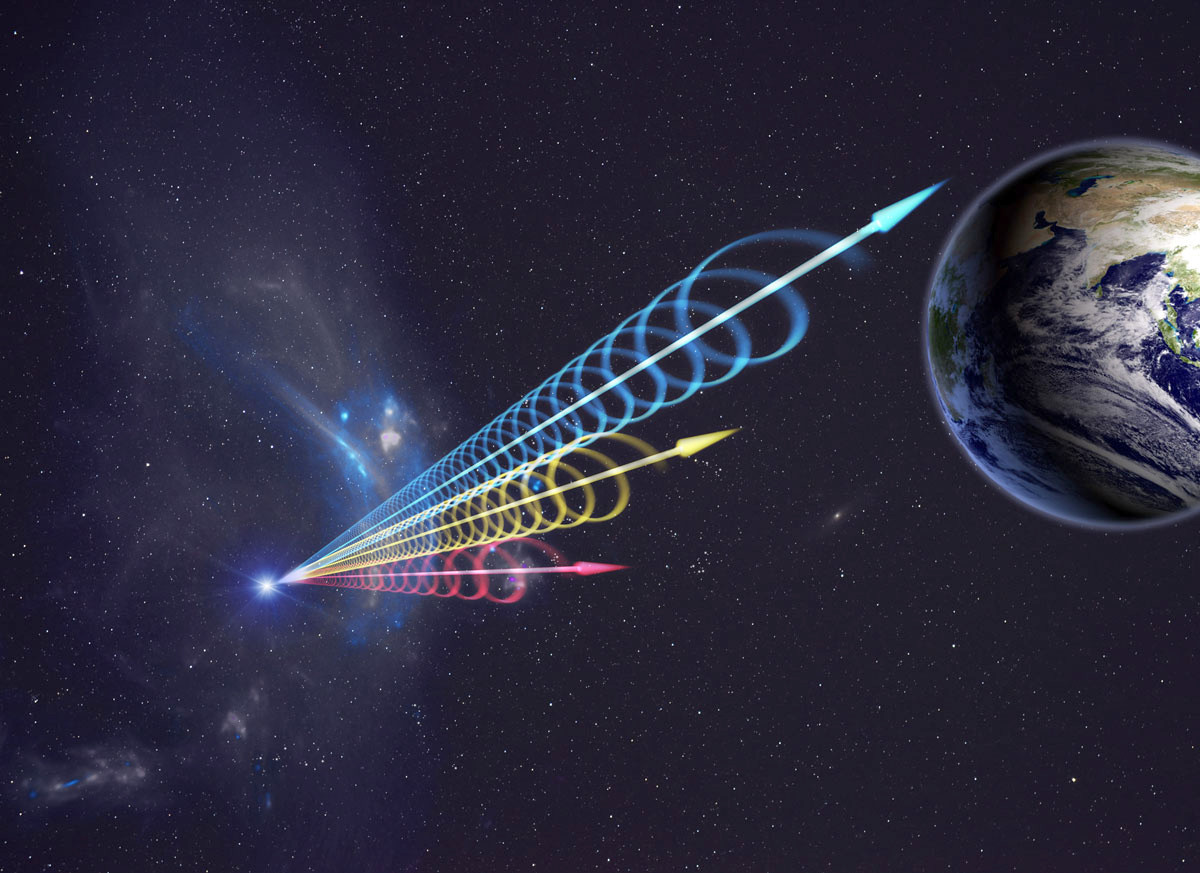

This smearing of the radio signal, known as dispersion delay, is often used to estimate distance in radio astronomy: the greater the dispersion, the further the object from Earth. In this case, the dispersion measure suggests the FRB originated as far as 6 billion light-years away.

Dispersion, however, masks the presence of an FRB within archival radio data.

The new software decreased the time required to analyse the data by counteracting the effects of dispersion, which restored the burst to its original appearance.

The team — primarily researchers with cosmology backgrounds — used this software to conduct an initial pass of the GBT data to flag any candidate signal. This yielded more than 6,000 possible FRBs, which were individually inspected by team member Hsiu-Hsien Lin from Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. His analysis winnowed the field until only one candidate remained.

Details hidden in polarisation

This one signal, however, was exceptional and contained more details about its polarisation than any previously identified. Prior to this detection, only circular polarisation was associated with an FRB. The new GBT study includes a detection of both circular and linear polarisation.

“Hidden within an incredibly massive dataset, we found a very peculiar signal, one that matched all the known characteristics of a fast radio burst, but with a tantalising extra polarisation element that we simply have never seen before,” said Jeffrey Peterson, a faculty member in Carnegie Mellon’s McWilliams Center for Cosmology.

Polarisation is a property of electromagnetic radiation, including light and radio waves, and indicates the orientation of the wave. Polarising sunglasses use this property to block out a portion of the Sun’s rays, and 3-D movies use it to achieve the illusion of depth.

The researchers used this additional information to determine that the radio light from the FRB exhibited Faraday rotation, a corkscrew-like twisting radio waves acquire by passing through a powerful magnetic field.

“This tells us something about the magnetic field that the burst travelled through on its way to us, giving a hint about the burst’s environment,” explained Masui. “It also gives the theorists a bit more to work with when they come up with explanations for these bursts.”

In addition, measurements of the dispersion delay can be used to place a lower limit on the size of the source region. In this case, the measurement rules out models for FRBs involving stars in our galaxy and, for the first time, shows that the FRB must have originated in another galaxy.

Further analysis of the signal reveals that it also passed through two distinct regions of ionised gas, called screens, on its way to Earth. By using the interplay between the two screens, the astronomers were able to determine their relative locations. The strongest screen is very near the burst’s source — within a hundred thousand light-years — placing it inside the source’s galaxy. Only two things could leave such an imprint on the signal, the researchers note: a nebula surrounding the source or the environment near the centre of a galaxy.

“Taken together, these remarkable data reveal more about an FRB than we have ever seen before and give us important constraints on these mysterious events,” concludes Masui. “We also have an exciting new tool to search through otherwise overwhelming archival data to uncover more examples and get closer to truly understanding their nature.”

The results are published in the journal Nature.