The GRAVITY instrument combines the light from multiple telescopes to form a virtual telescope up to 200 metres across, using a technique called interferometry. This enables the astronomers to detect much finer detail in astronomical objects than is possible with a single telescope.

Since the summer of 2015, an international team of astronomers and engineers led by Frank Eisenhauer (MPE), Garching, Germany, has been installing the instrument in specially adapted tunnels under the Very Large Telescope at ESO’s Paranal Observatory in northern Chile. This is the first stage of commissioning GRAVITY within the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI). A crucial milestone has now been reached: for the first time, the instrument successfully combined starlight from the four VLT Auxiliary Telescopes.

“During its first light, and for the first time in the history of long baseline interferometry in optical astronomy, GRAVITY could make exposures of several minutes, more than a hundred times longer than previously possible,” commented Frank Eisenhauer. “GRAVITY will open optical interferometry to observations of much fainter objects, and push the sensitivity and accuracy of high angular resolution astronomy to new limits, far beyond what is currently possible.”

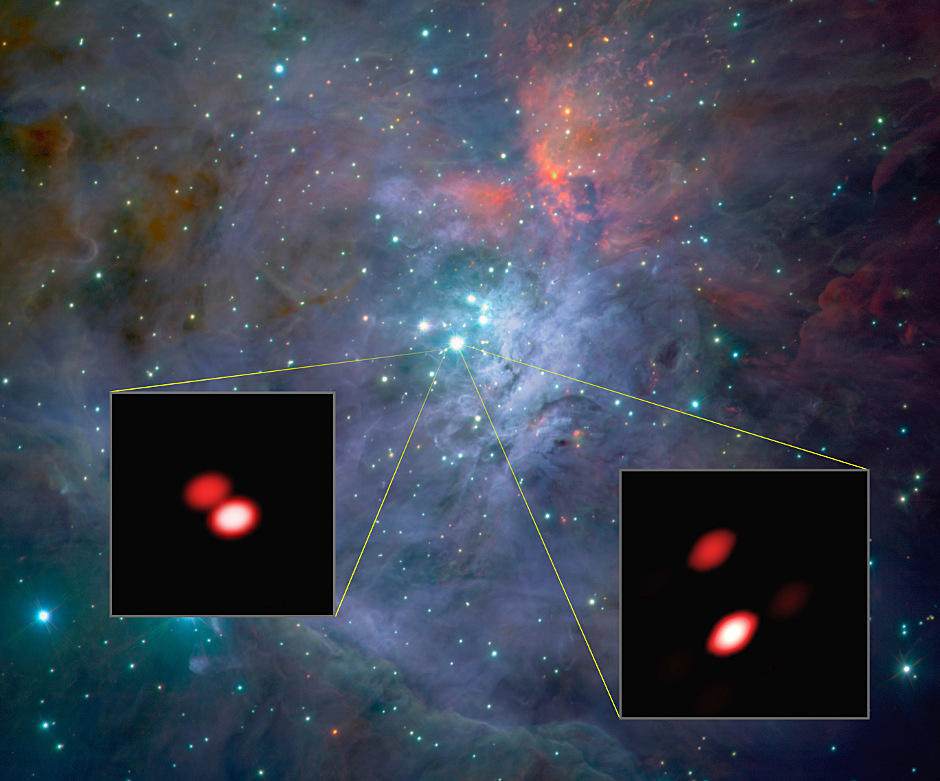

As part of the first observations the team looked closely at the bright, young stars known as the Trapezium Cluster, located in the heart of the Orion star-forming region. Already, from these first commissioning data, GRAVITY made a small discovery: one of the components of the cluster was found to be a double star.

The key to this success was to stabilise the virtual telescope for long enough, using the light of a reference star, so that a deep exposure on a second, much fainter object becomes feasible. Furthermore, the astronomers also succeeded in stabilising the light from four telescopes simultaneously — a feat not achieved before.

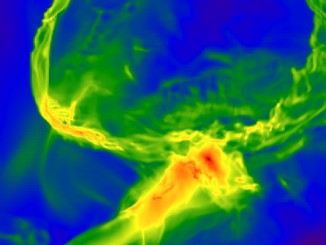

GRAVITY can measure the positions of astronomical objects on the finest scales and can also perform interferometric imaging and spectroscopy. If there were buildings on the Moon, GRAVITY would be able to spot them. Such extremely high resolution imaging has many applications, but the main focus in the future will be studying the environments around black holes.

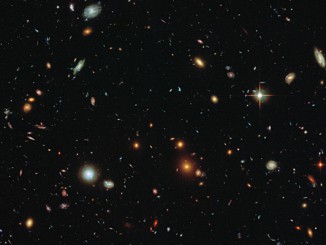

In particular, GRAVITY will probe what happens in the extremely strong gravitational field close to the event horizon of the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way — which explains the choice of the name of the instrument. This is a region where behaviour is dominated by Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. In addition, it will uncover the details of mass accretion and jets — processes that occur both around newborn stars (young stellar objects) and in the regions around the supermassive black holes at the centres of other galaxies. It will also excel at probing the motions of binary stars, exoplanets and young stellar discs, and in imaging the surfaces of stars.

So far, GRAVITY has been tested with the four 1.8-metre Auxiliary Telescopes. The first observations using GRAVITY with the four 8-metre VLT Unit Telescopes are planned for later in 2016.

The GRAVITY consortium is led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, in Garching, Germany. The other partner institutes are:

— LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, PSL Research University, CNRS, Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ. Paris 06, Univ. Paris Diderot, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Meudon, France

— Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany

— 1. Physikalisches Institut, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany

— IPAG, Université Grenoble Alpes/CNRS, Grenoble, France

— Centro Multidisciplinar de Astrofísica, CENTRA (SIM), Lisbon and Oporto, Portugal

— ESO, Garching, Germany