The black hole is still there, of course, but over the past ten years, it appears to have swallowed all the gas in its vicinity. With the gas fallen into the black hole, astronomers from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) were unable to detect the spectroscopic signature of the quasar, which now appears as an otherwise normal galaxy.

“This is the first time we’ve seen a quasar shut off this dramatically, this quickly,” says Jessie Runnoe of Pennsylvania State University, the study’s lead author, who is presenting this finding at the 227th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Kissimmee, Florida.

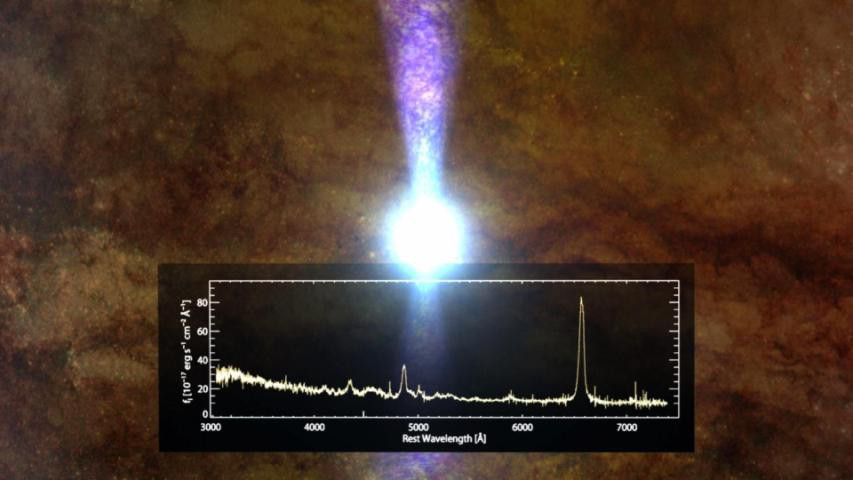

The key to the discovery was the SDSS’s long history of studying the sky. The survey first measured a spectrum of SDSS J1011+5442 way back in January 2003. Such a spectrum allows astronomers to understand the properties of the gas being swallowed by the black hole. In particular, looking at the strength of the prominent “hydrogen-alpha” line shows how much gas is currently falling into the central black hole. The SDSS measured another spectrum for SDSS J1011+5442 in early 2015, allowing astronomers to compare the rate of infalling gas between the two measurements twelve years apart.

“The difference was stunning and unprecedented,” said John Ruan of the University of Washington, lead author of a related paper as well as a member of Runnoe’s team. Ruan is also speaking at the AAS meeting. “The hydrogen-alpha emission dropped by a factor of 50 in less than twelve years, and the quasar now looks like a normal galaxy.” The change was so great that throughout the SDSS collaboration and astronomy community, the quasar became known as a “changing-look quasar.”

Over those twelve years, other telescopes have also been looking at this changing-look quasar, and Runnoe’s study made use of these additional observations as well. The additional data allowed the team to narrow down the period of change, finding that the quasar decreased by a factor of 50 in just a few years.

This animation shows an artist’s conception of the changing-look quasar as it evolved from 2003 to 2015. The beginning of the animation shows gas falling into the central black hole, along with the first SDSS spectrum. The black hole then uses up all the surrounding gas, and it is shown with the spectrum recently obtained by the TDSS component survey. The camera then pulls back to reveal the entire galaxy as the quasar shuts off, after which is looks like just another normal galaxy. The animation then fades into an artist’s conception of Hanny’s Voorwerp, a prior SDSS discovery that shows the record of a similar quasar shutting off.

So how do astronomers explain this unusual apparently disappearing black hole? Quasars result from giant black holes at the centres of distant galaxies. These black holes are enormous — in the case of the changing-look quasar, 50 million times the mass of the Sun — that infalling gas heats up to unimaginable millions of degrees. The hot gas glows so brightly that it is visible to us, all the way across the universe.

“If we saw this quasar swallowing gas in 2003 and don’t see it any more, that can mean one of three things,” says Ruan. One possibility is that a thick layer of dust is passing through the host galaxy, obscuring our view of the black hole region at its centre, but there is no way that any dust cloud could have moved fast enough to cause a 50-fold drop in brightness in just two years. Another possibility is that the bright quasar in 2003 was just a temporary flare caused by the black hole ripping apart a nearby star. While this possibility has been invoked in similar cases before, it cannot to explain the fact that the changing-look quasar had been shining for many years before it turned off.

The team’s conclusion is that the quasar has used up all the glowing-hot gas in its immediate vicinity, leading to a rapid drop in brightness. “Essentially, it has run out of food, at least for the moment,” says Runnoe. “We were fortunate to catch it before and after.”

The changing look quasar is the first major discovery of the Time-Domain Spectroscopic Survey (TDSS), one of the components of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s fourth phase. TDSS will continue for the next several years, promising many more surprising discoveries in the future.

“We are used to thinking of the sky as unchanging,” says Scott Anderson, the Principal Investigator of TDSS. “The SDSS gives us a great opportunity to see that change as it happens. In fact, we found this quasar because we went back to study thousands of quasars seen before. This discovery was only possible because the SDSS is so deep and has continued so long.”