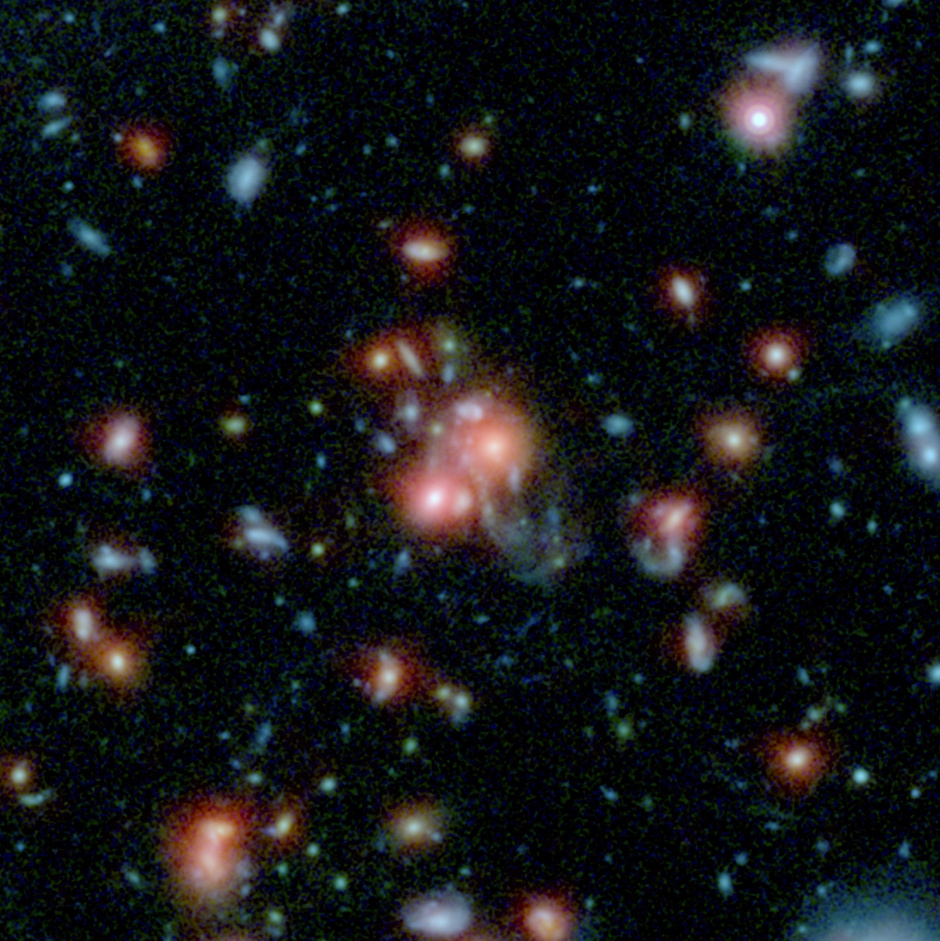

“Clusters of galaxies are rare regions of the universe consisting of hundreds of galaxies containing trillions of stars, as well as hot gas and mysterious dark matter,” said the lead author, Tracy Webb of McGill University, Canada. “The galaxies at the centres of clusters, called brightest cluster galaxies, are the most massive galaxies in the universe. How they become so huge is not well understood.”

What is so unusual about SpARCS 1049+56 is that it is forming stars at a prodigious rate, more than 800 solar masses per year — 800 times faster than in our own Milky Way.

This surprising new discovery was the result of collaborative synergy from ground-based observations from Keck Observatory and CFHT as well as space-based observations from NASA’s Hubble, Spitzer and Herschel Space Telescopes.

The Keck Observatory data was gathered by the powerful MOSFIRE infrared spectrograph and was crucial to determining SpARCS 1049+56’s distance from Earth as 9.8 billion light-years, that it contains at least 27 galaxies and that it has a total mass equal to about 400 trillion Suns.

The cluster was first identified from the University of California, Riverside-led, Spitzer Adaptation of the Red-sequence Cluster Survey, or SpARCS, which has discovered about 200 new distant galaxy clusters using deep ground-based optical observations combined with Spitzer Space Telescope infrared observations.

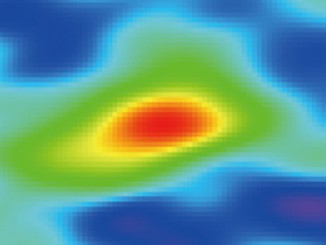

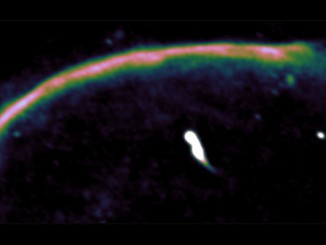

Because Spitzer and Herschel Space Telescopes detect infrared light — enabling observers to see hidden, dusty regions of star formation — they were able to reveal the full extent of the massive amount of star formation going on in SpARCS 1049+56. However, the resolution of the infrared observations was insufficient to pinpoint where all this star formation was coming from. Therefore, high-resolution follow-up optical observations were performed by the Hubble Space Telescope to reveal “beads on a string” at the centre of SpARCS 1049+56 which occur when, similar to a necklace, clumps of new star formation appear strung out like beads on filaments of hydrogen gas.

“Beads on a string” is a telltale sign of something known as a wet merger, which occurs when at least one galaxy in a collision between galaxies is gas rich, and this gas is converted quickly into new stars. The large amount of star formation and the “beads on a string” feature in the core of SpARCS 1049+56 are likely the result of the brightest cluster galaxy in the process of gobbling up a gas-rich spiral galaxy.

What is particularly interesting is that brightest cluster galaxies closer to the Milky Way are thought to grow by so-called dry mergers, collisions between gas-poor galaxies that do not result in the formation of new stars. The new discovery is one of the only known cases of a wet merger at the core of a galaxy cluster, and the most distant example ever found.

The team now aims to explore how common this type of growth mechanism is in galaxy clusters. Are there other messy eaters out there similar to SpARCS 1049+56, which are also munching on gas-rich galaxies? SpARCS 1049+56 may be a rarity or it may be the first of many cases at early times in our universe when messy eating was the norm.

The Keck Observatory findings were obtained as the result of a collaboration amongst UC faculty members Gillian Wilson (UCR), Michael Cooper (UCI) and Saul Perlmutter (UCB), postdoctoral researcher Brian Hayden (UCB), and graduate students Andrew DeGroot (UCR) and Ryan Foltz (UCR).

“It is very exciting to have discovered such an interesting object,” Wilson said. “Understanding its nature proved to be a real scientific challenge which required the combined efforts of an international team of astronomers and many of the world’s best telescopes to solve.”