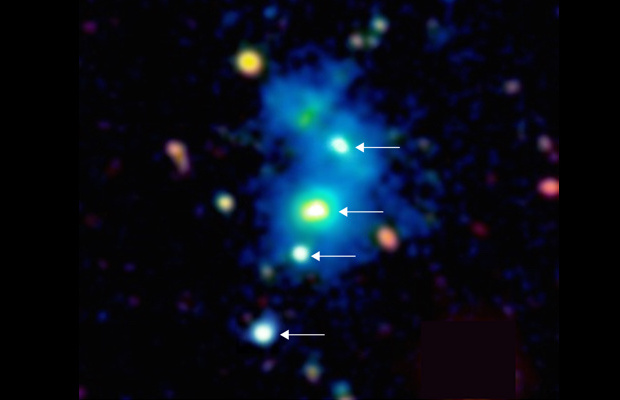

Quasars constitute a brief phase of galaxy evolution, powered by the infall of matter onto a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy. During this phase, they are the most luminous objects in the universe, shining hundreds of times brighter than their host galaxies, which themselves contain hundreds of billions of stars. But these hyper-luminous episodes last only a tiny fraction of a galaxy’s lifetime, which is why astronomers need to be very lucky to catch any given galaxy in the act. As a result, quasars are exceedingly rare on the sky, and are typically separated by hundreds of millions of light years from one another. The researchers estimate that the odds of discovering a quadruple quasar by chance is one in ten million. How on Earth did they get so lucky?

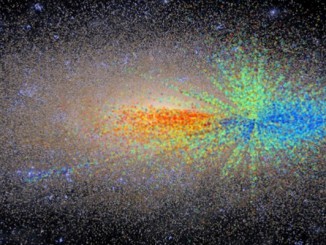

The four quasars are surrounded by a rare giant nebula of cool dense hydrogen gas — which the astronomers dubbed the “Jackpot Nebula”, given their surprise at discovering it around the already unprecedented quadruple quasar. The nebula emits light because it is irradiated by the intense glare of the quasars. In addition, both the quartet and the surrounding nebula reside in a rare corner of the universe with a surprisingly large amount of matter. “There are several hundred times more galaxies in this region than you would expect to see at these distances” explains J. Xavier Prochaska, professor at the University of California Santa Cruz and the principal investigator of the Keck observations.

Given the exceptionally large number of galaxies, this system resembles the massive agglomerations of galaxies, known as galaxy clusters, that astronomers observe in the present-day universe. But because the light from this cosmic metropolis has been travelling for 10 billion years before reaching Earth, the images show the region as it was 10 billion years ago, less than 4 billion years after the big bang. It is thus an example of a progenitor or ancestor of a present-day galaxy cluster, or proto-cluster for short.

Piecing all of these anomalies together, the researchers tried to understand what appears to be their incredible stroke of luck. Hennawi explains “if you discover something which, according to current scientific wisdom, should be extremely improbable, you can come to one of two conclusions: either you just got very lucky, or you need to modify your theory.”

The researchers speculate that some physical process might make quasar activity much more likely in specific environments. One possibility is that quasar episodes are triggered when galaxies collide or merge, because these violent interactions efficiently funnel gas onto the central black hole. Such encounters are much more likely to occur in a dense proto-cluster filled with galaxies, just as one is more likely to encounter traffic when driving through a big city.

“The giant emission nebula is an important piece of the puzzle,” says Fabrizio Arrigoni-Battaia, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy who was involved in the discovery, “since it signifies a tremendous amount of dense cool gas.” Supermassive black holes can only shine as quasars if there is gas for them to swallow, and an environment that is gas rich could provide favorable conditions for fuelling quasars.

On the other hand, given the current understanding of how massive structures in the universe form, the presence of the giant nebula in the proto-cluster is totally unexpected. According to Sebastiano Cantalupo of ETH Zurich, a co-author of the study: “Our current models of cosmic structure formation based on supercomputer simulations predict that massive objects in the early universe should be filled with rarefied gas that is about ten million degrees, whereas this giant nebula requires gas thousands of times denser and colder.”

“Extremely rare events have the power to overturn long-standing theories,” says Hennawi. As such, the discovery of the first quadruple quasar may force cosmologists to rethink their models of quasar evolution and the formation of the most massive structures in the universe.