Around 500 astronomers and space scientists will gather at Venue Cymru in Llandudno, Wales, from 5-9 July, for the Royal Astronomical Society National Astronomy Meeting 2015 (NAM2015, Cyfarfod Seryddiaeth Cenedlaethol 2015). The conference is the largest regular professional astronomy event in the UK and will see leading researchers from around the world presenting the latest work in a variety of fields. In his first report from the event this week, science writer and editor Kulvinder Singh Chadha presents his pick of the day’s presentations:

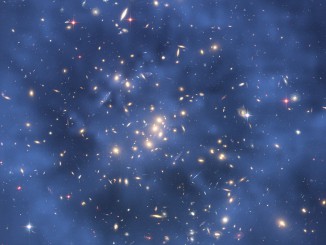

Rings and Loops in the stars: Planck’s stunning new images

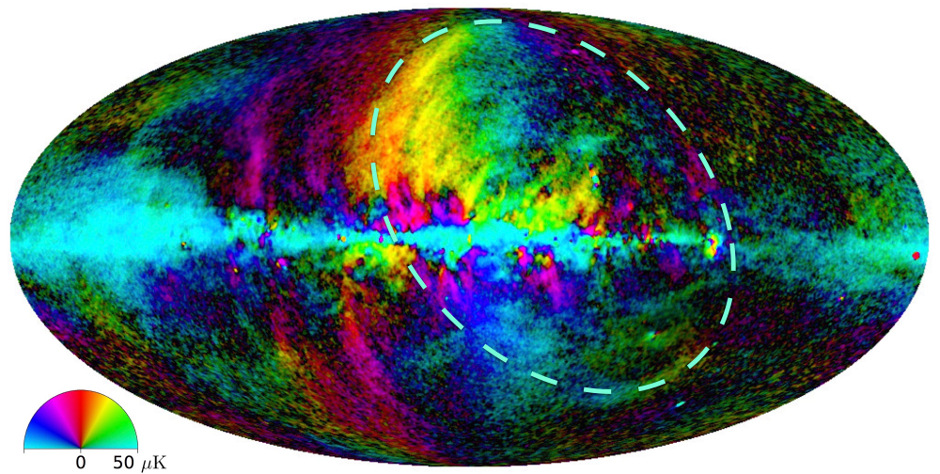

The new maps show vast regions of the sky producing anomalous microwave radiation (AME). this process was only discovered in 1997 and could account for a large amount of galactic microwave emission around 1-centimetre in wavelength. A 200 light-year-wide dust ring around the Lambda Orionis Nebula (the ‘head’ of the familiar Orion constellation) is one area where it is exceptionally bright. This is the first time the ring’s been seen in this way.

A wide-field map also shows synchrotron loops and spurs (where charged particles spiral around magnetic fields at close to light speed), including the huge Loop 1, discovered over 50 years ago. Even now, its distance is still very uncertain. It could be anywhere between 400 to 25,000 light-years away. Therefore, although it covers around a third of the sky, it’s impossible to say how big it actually is.

School solar satellite success

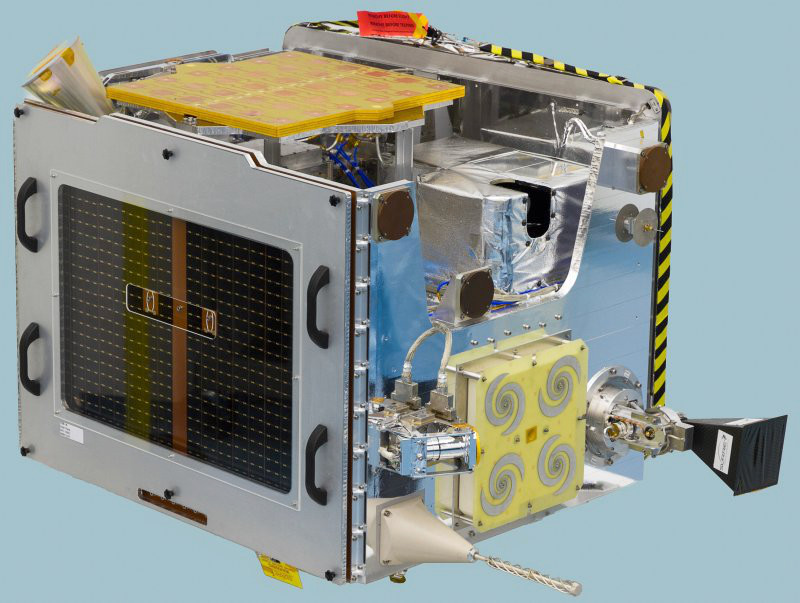

“When orbiting the sunlit side of Earth, the signal detected by LUCID is dominated by the solar wind, allowing it to map the number and energy of protons and electrons against geographical area and time. But when it’s shielded from the Sun on the night-time leg of its orbit, we can identify cosmic ray events,” says Hewitt, who has just finished his GCSEs. He has worked with a team of other students to prepare LUCID for anticipated major data runs. The sheer computing power required for the process has meant that Hewitt has become the youngest student certified to use GridPP, the UK’s segment of a worldwide-grid of computers processing data from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). This grid numbers thousands of computers.

LUCID tracks the direction of incoming cosmic ray and solar wind particles in three dimensions and determines the type of particles (whether protons, electrons, etc), the energy they deposit and the resulting radiation dose. Monitoring these energetic particles is important for understanding space weather and protecting astronauts from high levels of radiation. The mission has captured half a million events during its commissioning phase and a further 250,000 will be captured during the summer to build up a map of Low Earth Orbit radiation environment.

The satellite was launched on 8 July 2014 on the Innovate UK-funded TechDemoSat-1, which carries payloads from a number of UK academic and governmental institutions, having been first conceived by students in 2008. It is one of a number of research projects developed at the Langton Star Centre. “LUCID has been developed from pixel detectors used at the LHC, which were originally designed for medical imaging,” says Hewitt. “This type of detector has never been used before in open space and our first data was extremely noisy but we have optimised detector settings for day and night captures.”