Io, the innermost of the four moons of Jupiter discovered by Galileo in January 1610, is only slightly bigger than our own Moon but is the most geologically active body in our Solar System. Hundreds of volcanic areas dot its surface, which is mostly covered with sulfur and sulfur dioxide.

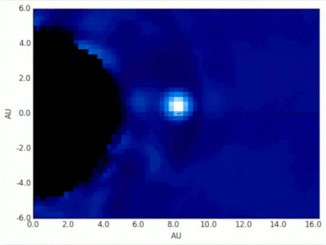

With its two 8.4-metre mirrors set on the same mount 6 metres apart, the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT), by combining the light through interferometry, provide images at the same level of detail a 22.8-metre telescope would reach. Thanks to the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer (LBTI), an international team of researchers was able to look at Loki Patera, revealing details as never before seen from Earth; their study is published today in the Astronomical Journal.

“We combine the light from two very large mirrors coherently so that they become a single, extremely, large mirror,” says Al Conrad, the lead author of the study and a scientist at the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory (LBTO). “In this way, for the first time we can measure the brightness coming from different regions within the lake.”

For Phil Hinz, who leads the LBTI project at the University of Arizona Steward Observatory, this result is the outcome of a nearly fifteen-year development. “We built LBTI to form extremely sharp images. It is gratifying to see the system work so well.” Hinz notes that this is only one of the unique aspects of LBTI. “We built the system both to form sharp images and to detect dust and planets around nearby stars at extremely high dynamic range. Recent results from LBTI on Eta Corvi and HR 8799 are great examples of its potential.”

LMIRcam, the camera recording the images at the very heart of LBTI in the 3 to 5 micrometres near-infrared band, was the thesis work of Jarron Leisenring as graduate student at the University of Virginia. For Leisenring, now an instrument scientist for NIRCam (the Near InfraRed Camera for the James Webb Space Telescope) at Steward Observatory, “these observations mark a major milestone for me and the instrument team. LMIRcam has already been very productive these past few years; now, interferometric combination provides the last step in harnessing LBTI’s full potential and enabling a whole host of new scientific opportunities.”

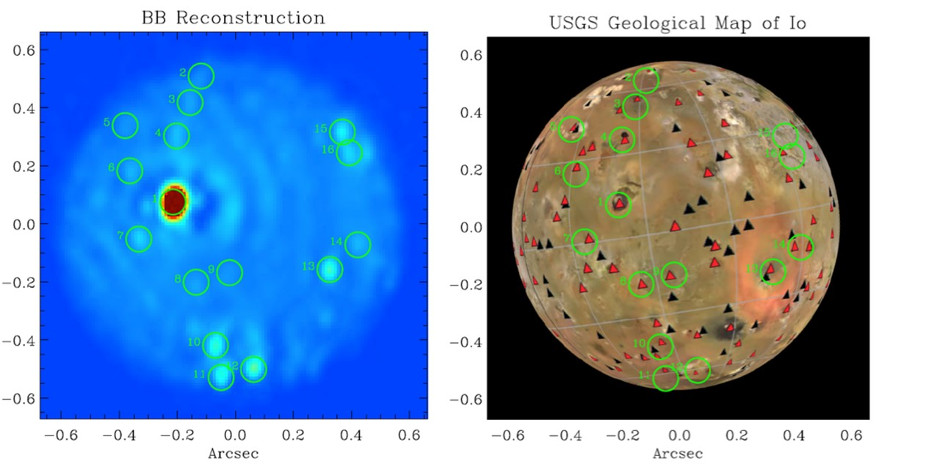

Many raw images delivered by LMIRcam are combined to form a single high-resolution image. “LBTI raw images are crossed by interference fringes. Therefore, these raw images do not look very sharp,” explains Gerd Weigelt, a Professor at the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie (Bonn, Germany). “However, modern image reconstruction (deconvolution) methods allow us to overcome the interference fringes and achieve a spectacular image resolution.”

“Data processing based on deconvolution methods,” adds Mario Bertero, a professor in Information Science at the University of Genoa (Italy), “are basic for detecting details not directly distinguishable in the interferometric images. However they can generate artifacts and, for this reason, it is important to process the images with different methods for discriminating between relevant details and artifacts.”

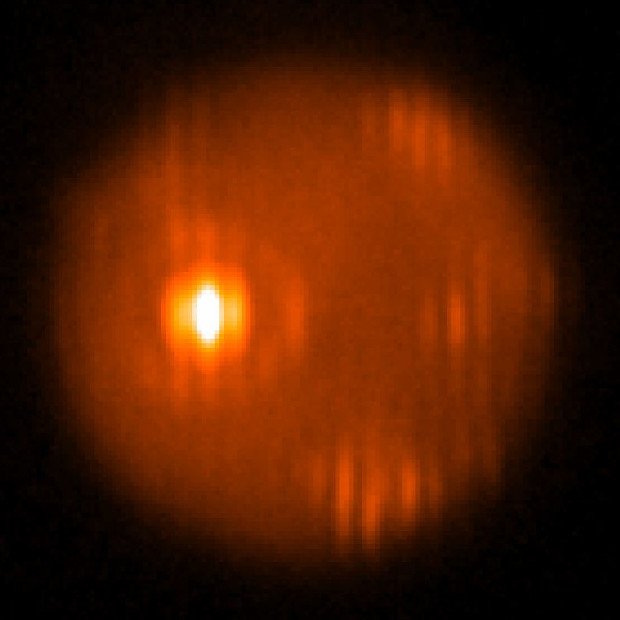

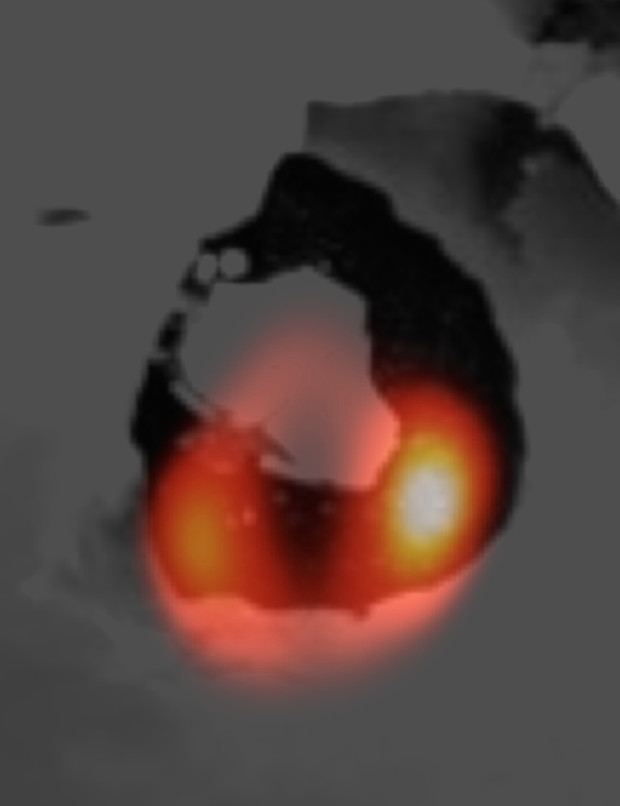

“While we have seen bright emissions — always one unresolved spot — “pop up” at different locations in Loki Patera over the years,” explains Imke de Pater, a professor at the University of California in Berkeley, “these exquisite images from the LBTI show for the first time in ground-based images that emissions arise simultaneously from different sites in Loki Patera. This strongly suggests that the horseshoe-shaped feature is most likely an active overturning lava lake, as hypothesised in the past.”

“Two of the volcanic features are at newly active locations,” explains Katherine de Kleer, a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley. “They are located in a region called the Colchis Regio, where an enormous eruption took place just a few months earlier, and may represent the aftermath of that eruption. The high resolution of the LBTI allows us to resolve the residual activity in this region into specific active sites, which could be lava flows or nearby eruptions.”

“Studying the very dynamic volcanic activity on Io, which is constantly reshaping the moon’s surface, provides clues to the interior structure and plumbing of this moon,” remarked team member Chick Woodward of the University of Minnesota, “helping to pave the way for future NASA missions such as the Io Volcano Observer. Io’s highly elliptical orbit close to Jupiter is constantly tidally stressing the moon, like the squeezing of a ripe orange, where the juice can escape through cracks in the peel.”

For Christian Veillet, director of the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory (LBTO), “this study marks a very important milestone for the observatory. The unique feature of the binocular design of the telescope, originally proposed more than 25 years ago, is its ability to provide images with the level of detail (resolution) only a single-aperture telescope at least 22.8 metres in diameter could reach. The spectacular observations of Io published today are a tribute to the many who believed in the LBT concept and worked very hard over more than two decades to reach this milestone.”

Veillet adds: “While there is still much work ahead to make the LBT/LBTI combination a fully operational instrument, we can safely state that the Large Binocular Telescope is truly a forerunner of the next generation of extremely large telescopes slated to see first light in a decade (or more) from now.”