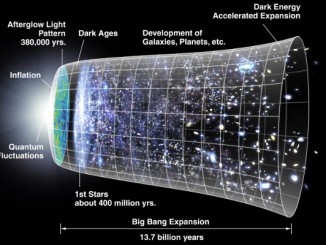

The light chemical element lithium is one of the few elements that is predicted to have been created by the Big Bang, 13.8 billion years ago. But understanding the amounts of lithium observed in stars around us today in the Universe has given astronomers headaches. Older stars have less lithium than expected, and some younger ones up to ten times more.

Since the 1970s, astronomers have speculated that much of the extra lithium found in young stars may have come from novae — stellar explosions that expel material into the space between the stars, where it contributes to the material that builds the next stellar generation. But careful study of several novae has yielded no clear result up to now.

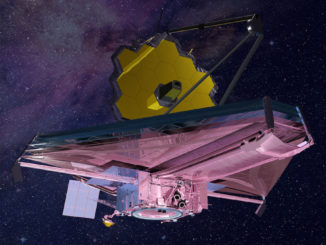

A team led by Luca Izzo (Sapienza University of Rome, and ICRANet, Pescara, Italy) has now used the FEROS instrument on the MPG/ESO 2.2-metre telescope at the La Silla Observatory, as well the PUCHEROS spectrograph on the ESO 0.5-metre telescope at the Observatory of the Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile in Santa Martina near Santiago, to study the nova Nova Centauri 2013 (V1369 Centauri). This star exploded in the southern skies close to the bright star Beta Centauri in December 2013 and was the brightest nova so far this century — easily visible to the naked eye.

Co-author Massimo Della Valle (INAF–Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Naples, and ICRANet, Pescara, Italy) explains the significance of this finding: “It is a very important step forward. If we imagine the history of the chemical evolution of the Milky Way as a big jigsaw, then lithium from novae was one of the most important and puzzling missing pieces. In addition, any model of the Big Bang can be questioned until the lithium conundrum is understood.”

The mass of ejected lithium in Nova Centauri 2013 is estimated to be tiny (less than a billionth of the mass of the Sun), but, as there have been many billions of novae in the history of the Milky Way, this is enough to explain the observed and unexpectedly large amounts of lithium in our galaxy.

Authors Luca Pasquini (ESO, Garching, Germany) and Massimo Della Valle have been looking for evidence of lithium in novae for more than a quarter of a century. This is the satisfying conclusion to a long search for them. And for the younger lead scientist there is a different kind of thrill:

“It is very exciting,” says Luca Izzo, “to find something that was predicted before I was born and then first observed on my birthday in 2013!”