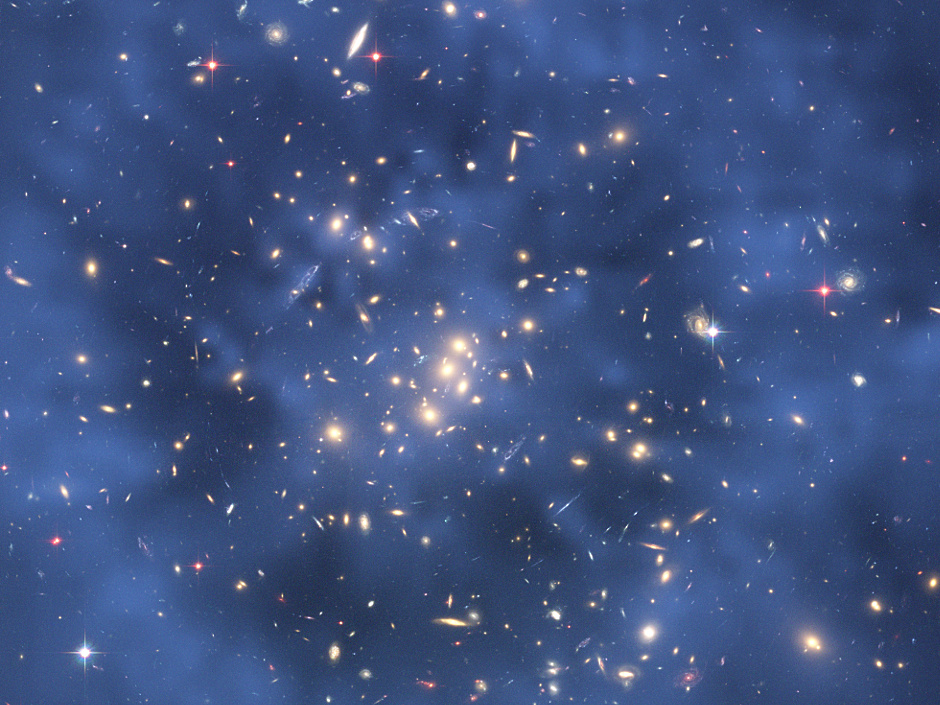

For decades, researchers have tried to detect this invisible dark matter. Several types of devices have been put up on Earth and in space to capture the particles that dark matter is supposed to consist of, and experiments have attempted to create a dark matter particle by colliding ordinary matter particles at very high temperatures.

If such a collision should one day succeed, we would however not be able to directly see the produced dark matter particle. It would immediately pass on and fly away from the detectors — but it will take some energy with it, and this energy loss will be recorded and indicate that a dark particle had been produced.

Despite all these initiatives no dark particle has yet been detected.

“Maybe it’s because we have looked after dark particles in a way that will never be able to reveal them. Maybe dark matter is of a different character and needs to be looked for in a different way,” says Martin Sloth, associate professor at The Centre for Cosmology and Particle Physics Phenomenology (CP3-Origins), University of Southern Denmark.

Together with his postdoc McCullen Sandora from CP3-Origins and postdoc Mathias Garny from CERN, he now presents a new model for what dark matter might be in the journal Physical Review Letters.

For decades, physicists have been working on the theory that dark matter is light and therefore interacts weakly with ordinary matter. This means that the particles are capable of being produced in colliders. This theory’s dark particles are called weakly-interacting massive particles (WIMPs), and they are theorised to have been created in an inconceivably large number shortly after the birth of the universe 13.7 billion years ago.

“But since no experiments have ever seen even a trace of a WIMP, it could be that we should look for a heavier dark particle that interacts only by gravity and thus would be impossible to detect directly,” says Martin Sloth.

Sloth and his colleagues call their version of such a heavy particle a PIDM particle (Planckian Interacting Dark Matter).

In their new model, they calculated how the required number of PIDM particles could have been created in the early universe.

“It was possible, if it was extremely hot. To be more precise the temperatures in the early universe must have been the highest possible in the Big Bang theory,” says Sloth.

Whether this was the case or not can be tested. He explains further: “If the universe indeed was as hot as calculated in our model, several gravitational waves from the very early childhood of the universe would have been created. We might be able to find out in the near future.”

With this Sloth refers to a number of planned experiments around the world that will be able to detect signals from very early gravitational waves.

“If these experiments do not detect such signals, then our model will be falsified. Thus gravitational waves can be used to test our model,” he says.

More than ten different experiments are planned. They aim to measure the polarisation of the cosmic background radiation, either from the ground or with instruments sent up in a balloon or satellite to avoid atmospheric disturbances.