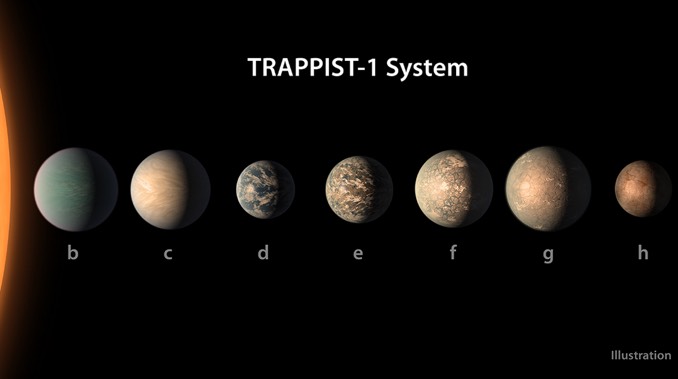

TRAPPIST-1, a small, Jupiter-size M dwarf about 39 light years from Earth, hosts at least seven planets, three of them orbiting in the star’s habitable zone where temperatures could allow water to exist on the surface – a key factor in the development of life as it’s currently understood.

New research indicates all of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds were baked during an extremely hot early phase of their star’s history, boiling away any water that may have existed and leaving dense, Venus-like atmospheres in its wake. But one of the worlds – TRAPPIST-1e – may have survived that fate to become a more Earth-like water world.

While there are still unknowns and assumptions in the research, “this is a whole sequence of planets that can give us insight into the evolution of planets, in particular around a star that’s very different from ours, with different light coming off of it,” said Andrew Lincowski, a University of Washington post-doctoral student and lead author of a paper in the Astrophysical Journal. “It’s just a gold mine.”

Lincowski’s team combined terrestrial climate modeling with photochemistry to simulate the environments of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds.

They concluded TRAPPIST-1b, the closest planet to the star, is likely too hot even for clouds of sulfuric acid to form. Planets c and d are hot enough to resemble Venus while the outer planets f, g and h could either be Venus-like or frozen, depending on how much water was present early on.

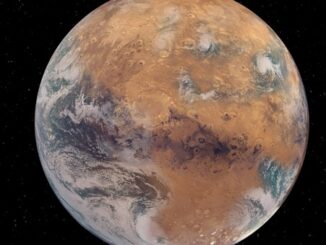

Only TRAPPIST-1e appears to have the potential to be an Earth-like planet today, but it’s not a sure thing. It depends on how much water was initially present.

“If planet TRAPPIST-1e did not lose all of its water during this phase, today it could be a water world, completely covered by a global ocean,” Lincowski said. “In this case, it could have a climate similar to Earth.”

Co-author Jacob Lustig-Yaeger said the research “informs the scientific community of what we might expect to see for the TRAPPIST-1 planets with the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope.”