Jupiter’s southerly declination ensures that antipodean observers fare better where, even at the end of July, the planet transits high in the northern sky around the end of evening nautical twilight. If you need some help identifying the planet, the 8-day-old waxing gibbous Moon lies close by at dusk on 20 July (21 July in the Southern Hemisphere). As seen from the UK, the Moon lies 4⅓ degrees to the upper right of Jupiter at 10:30pm BST on Friday, 20 July 2018.

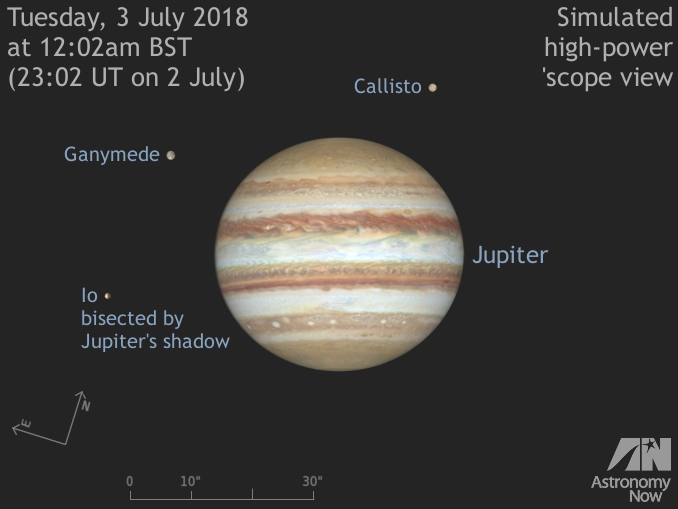

Jupiter’s angular size shrinks from 41.4 to 37.9 arcseconds over the course of July as the planet’s distance grows, but a telescope magnifying just 50× is still sufficient to enlarge it to the same size as an average full Moon appears to the unaided eye. In order to see most of the following events, you’ll need powers of 100× or more and preferably a telescope of 10-cm (4-inch) aperture or larger.

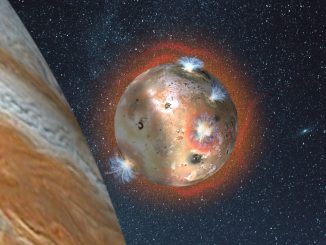

The orbital motion of Jupiter’s bright Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto cause them to alternately pass in front of (transit) Jupiter, be hidden (occulted) by their parent planet or its shadow (eclipsed). However, the slight inclination of their orbits to our line of sight means that outermost moon Callisto currently passes north or south of Jupiter’s disc (see the graphic at the top of this page).

The transit of a Galilean moon across the face of Jupiter can be challenging to view, but their shadows are much easier to see in modest (4-inch, or 10-cm aperture) telescopes of good quality. At magnifications of 100x or more, Galilean shadow transits look like inky black dots slowly drifting across the face of their parent planet.

The table below lists all readily observable transits of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot (when the giant anticyclonic storm feature crosses an imaginary line joining Jupiter’s north and south poles), Galilean moon and shadow transits, occultations and eclipses visible from the British Isles throughout the month of July. Note that the Great Red Spot is well shown for up to an hour either side of the predicted transit time.