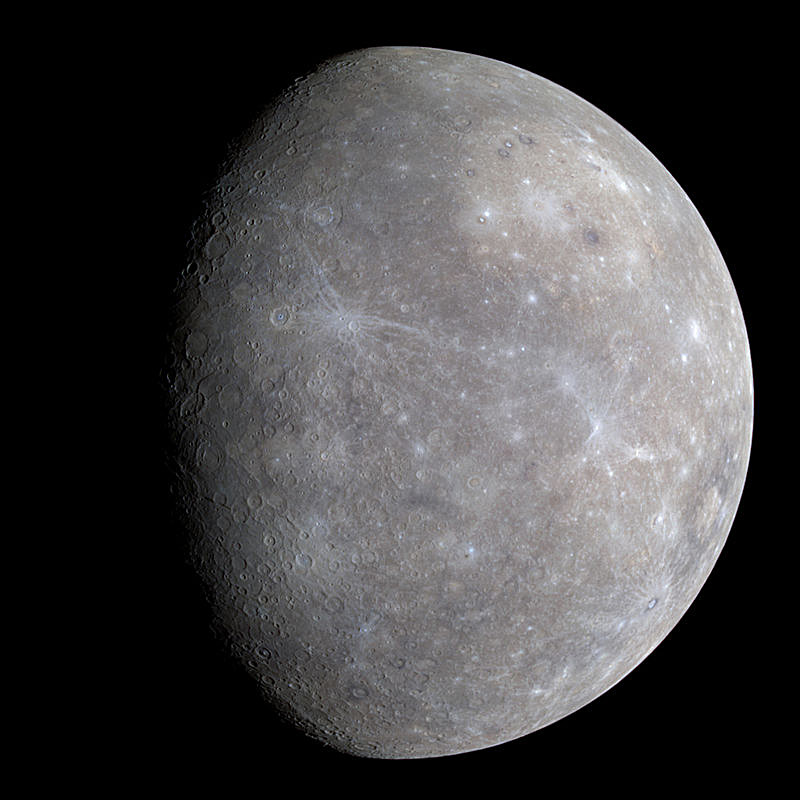

Mercury’s orbit is also quite eccentric, so the farthest that we can ever see the innermost planet from the Sun varies between 18 and 28 degrees — scarcely more than the span of an outstretched hand held at arm’s length. Consequently, we can only see Mercury with the naked eye either in the west at dusk or in the east at dawn, but rarely in a truly dark sky.

(If one lived near the equator, then under very favourable circumstances it might be possible to see Mercury at eastern elongation setting in the west after the end of evening astronomical twilight, or at western elongation rising in the east just before the onset of astronomical twilight.)

The trick to finding Mercury lies in observing from a location that offers you a flat and unobscured eastern horizon at a time when the sky is sufficiently dark to see it in the twilight, but not so early that it’s too close to the horizon and lost in the murk. It so happens that for most of the UK these criteria are fulfilled one hour before sunrise at this time of year. Our interactive online Almanac is a convenient place to find this information (instructions for its use may be found here)

In the Almanac, select the nearest town or city to your location and ensure that “Daylight Savings Time” is ticked for the UK. At the top right of the display, use the pull-down menu to select “Bright planets last/first visible” to display your local circumstances of the best time in the morning to make the attempt. Alternatively, just subtract one hour from the calculated local sunrise time for the date in question.

Once you have determined an hour before sunrise for your location on any given date, a good rule of thumb for the UK at this time of year is that this time is reached two minutes later each successive morning. If you can find a location with an unobstructed view due east an hour before sunrise, Mercury lies 6 degrees above the horizon from approximately 25 September until about 5 October as seen from the centre of the British Isles.

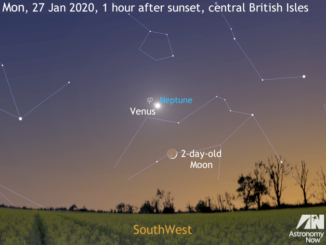

It also happens that the waning crescent Moon is a very convenient celestial guide to Mercury during the few remaining September mornings, as depicted in the animated graphic at the top of the page. The very old lunar crescent, just 43 hours before new Moon, lies 2 degrees (well within a binocular field of view) to the right of magnitude -0.5 Mercury at dawn on Thursday, 29 September in the UK.

Mercury lies in southern Leo for much of the period in question, steadily growing brighter during the period of visibilty as more of its disc is illuminated, but its angular size is decreasing. The planet reaches magnitude zero on 26 September, crosses the constellation border into Virgo early on 3 October, before attaining magnitude -1.0 by the morning of 6 October.

Inside the magazine

For a comprehensive guide to observing all that is happening in the sky of the month ahead, tailored to Western Europe, North America and Australasia, obtain a copy of the October 2016 edition of Astronomy Now.

Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.