The Quadrantids have the potential to put on an impressive display rivalling that of the August Perseids or the December Geminids, with figures of 60 to 120 meteors per hour often quoted. Quadrantids are slow to medium speed entering the Earth’s atmosphere with velocities of around 43 kilometres (27 miles) per second, with brighter examples often appearing yellow and blue. About ten percent of these will leave persistent glowing trails, too. So why is it such an underobserved shower? The problem lies in the fact that most of the peak activity occurs within a six-hour window centred on a short, sharp maximum.

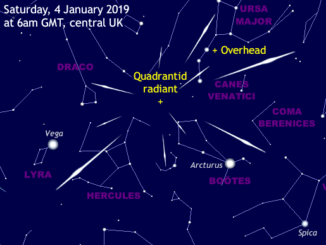

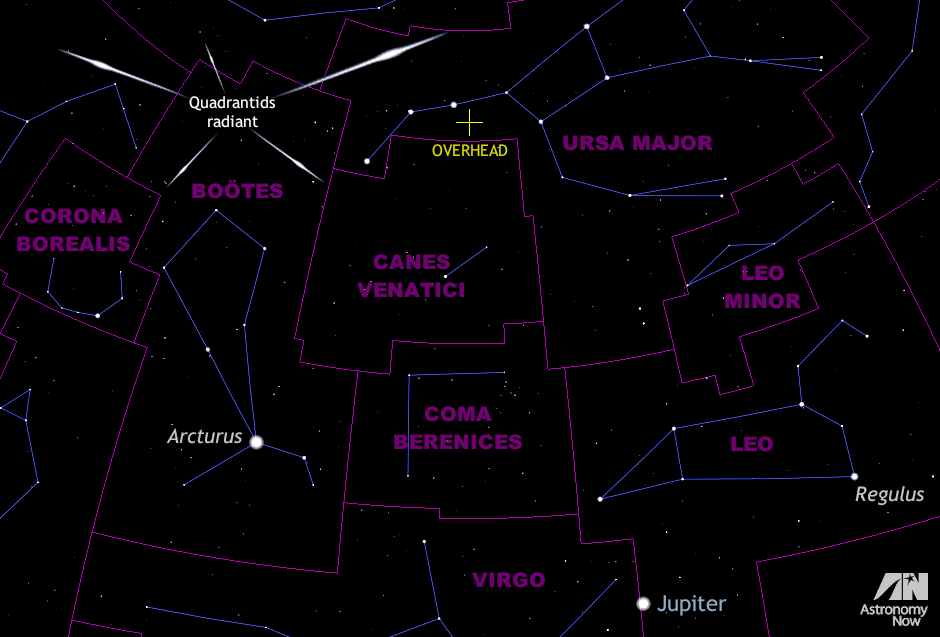

The International Meteor Organisation (IMO) predicts that the shower will peak at 8am GMT on Monday, 4 January. With sunrise occurring at 8:28am GMT for the centre of the British Isles on this date, the sky will therefore be in bright twilight for much of the UK. If this main prediction holds true, then North America might get the best show. However, a second prediction from meteor dynamicist Jérémie Vaubaillon suggests that the Quadrantid peak will arrive some hours earlier, which will certainly favour Western Europe. For UK observers, the best time to mount your vigil might be between 3am and 6am GMT on 4 January.

A 24-day-old waning crescent Moon just four degrees to the lower left of planet Mars in Virgo rises at 2:20am GMT on 4 January as seen from the centre of the British Isles, but it shouldn’t detract too much from the brighter meteors that one might see.

The faintest meteors are the most plentiful, so to maximise your chances you should find a safe location that is as far removed from streetlights and other sources of light pollution as you can and allow your eyes to become fully dark adapted. Ensure that you are dressed in multiple layers of clothing with warm boots or shoes, gloves and — particularly important — a hat, since a large proportion of heat is otherwise lost through the head.

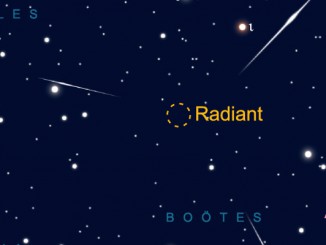

A thermos flask of your favourite hot beverage and a lounger chair is a good idea as you’ll be still for long periods during your watch. Observing in company is always more fun too! Don’t concentrate on the radiant but at a point about 40 degrees (or twice the span of an outstretched hand at arm’s length) to one side of it and about half way from the horizon to overhead.

The source of the Quadrantids is most likely a small solar system body known as (196256) 2003 EH1 that was discovered in March 2003. It completes a circuit of the Sun every 5.52 years in a highly inclined, eccentric orbit and last came to perihelion in March 2014. Most likely an extinct comet, 2003 EH1 could be related to the break-up of Comet C/1490 Y1 that was observed by Chinese, Japanese and Korean astronomers 525 years ago.

Inside the magazine

Find out more about what’s up in the night sky in the January 2016 edition of Astronomy Now. Never miss an issue by subscribing to the UK’s biggest astronomy magazine. Also available for iPad/iPhone and Android devices.