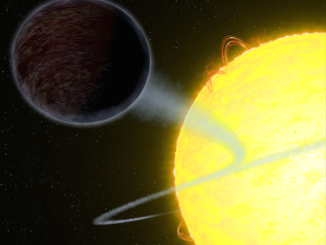

First discovered in 2008, beta (β) Pictoris b is a gas giant planet ten to twelve times the mass of Jupiter, with an orbit roughly the diameter of Saturn’s. It is part of a dynamic and complex system that includes comets, orbiting gas clouds, and an enormous debris disc that in our solar system would extend from Neptune’s orbit to nearly two thousand times the Sun/Earth distance. Because the planet and debris disc interact gravitationally, the system provides astronomers with an ideal laboratory to test theories on the formation of planetary systems beyond ours.

Maxwell Millar-Blanchaer, a PhD-candidate in the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of Toronto, is lead author of a paper published on 16 September in the Astrophysical Journal. The paper describes observations of the β Pictoris system made with the Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) instrument on the Gemini South telescope in Chile.

The images in the series represent the most accurate measurements of the planet’s position ever made,” says Millar-Blanchaer. “In addition, with GPI, we’re able to see both the disc and the planet at the exact same time. With our combined knowledge of the disc and the planet we’re really able to get a sense of the planetary system’s architecture and how everything interacts.”

The paper includes refinements to measurements of the exoplanet’s orbit and the ring of material circling the star which shed light on the dynamic relationship between the two. It also includes the most accurate measurement of the mass of β Pictoris to date and shows it is very unlikely that β Pictoris b will pass directly between us and its parent star.

“It’s remarkable that Gemini is not only able to directly image exoplanets but is also capable of effectively making movies of them orbiting their parent star,” said Chris Davis, astronomy division program director at the National Science Foundation, which is one of five international partners that funds the Gemini twin telescopes’ operation and maintenance. “Beta Pictoris is a special target. The disc of gas and dust from which planets are currently forming was one of the first to be observed and is a fabulous laboratory for the study of young solar systems.”

Astronomers have discovered nearly two thousand exoplanets in the past two decades but most have been detected with instruments — like the Kepler space telescope — that use the transit method of detection: astronomers detect a faint drop in a star’s brightness as an exoplanet transits or passes between us and the star, but do not see the exoplanet itself. With GPI, astronomers image the actual planet — a remarkable feat given that an orbiting world typically appears a million times fainter than its parent star. This is possible because GPI’s adaptive optics sharpen the image of the target star by cancelling out the distortion caused by the Earth’s atmosphere; it then blocks the bright image of the star with a device called a coronagraph, revealing the exoplanet.

Laurent Pueyo is with the Space Telescope Science Institute and a co-author on the paper. “It’s fortunate that we caught β Pictoris b just as it was heading back — as seen from our vantage point — toward β Pictoris,” says Pueyo. “This means we can make more observations before it gets too close to its parent star and that will allow us to measure its orbit even more precisely.”

GPI is a groundbreaking instrument that was developed by an international team led by Stanford University’s Prof. Bruce Macintosh (a University of Toronto alumnus) and the University of California Berkeley’s Prof. James Graham (former director of the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of Toronto).

In August 2015, the team announced its first exoplanet discovery: a young Jupiter-like exoplanet designated 51 Eridani b. It is the first exoplanet to be discovered as part of the GPI Exoplanet Survey (GPIES) which will target 600 stars over the next three years.