Using Keck Observatory’s powerful infrared spectrograph called MOSFIRE, the team dated the galaxy by detecting its Lyman-alpha emission line — a signature of hot hydrogen gas heated by strong ultraviolet emission from newly born stars. Although this is a frequently detected signature in galaxies close to Earth, the detection of Lyman-alpha emission at such a great distance is unexpected as it is easily absorbed by the numerous hydrogen atoms thought to pervade the space between galaxies at the dawn of the universe. The result gives new insight into ‘cosmic reionisation,’ the process by which dark clouds of hydrogen were split into their constituent protons and electrons by the first generation of galaxies.

“We frequently see the Lyman-alpha emission line of hydrogen in nearby objects as it is one of most reliable tracers of star-formation,” said California Institute of Technology (Caltech) astronomer, Adi Zitrin, lead author of the discovery paper. “However, as we penetrate deeper into the universe, and hence back to earlier times, the space between galaxies contains an increasing number of dark clouds of hydrogen which absorb this signal.”

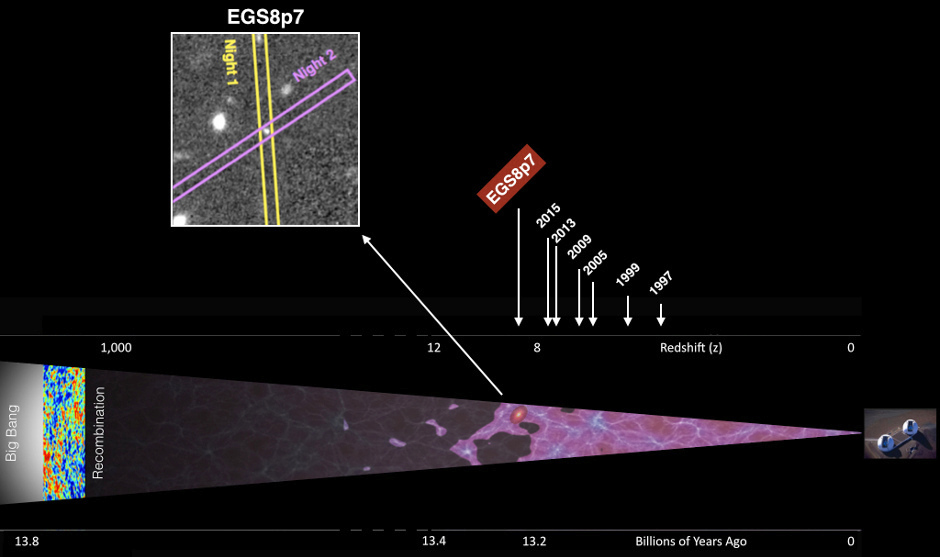

Recent work has found the fraction of galaxies showing this prominent line declines markedly after when the universe was about a billion years old, which is equivalent to a redshift of about 6. Redshift is a measure of how much the universe has expanded since the light left a distant source and can only be determined for faint objects with a spectrograph on a powerful large telescope such as the Keck Observatory’s twin 10-metre telescopes, the largest on Earth.

“The surprising aspect about the present discovery is that we have detected this Lyman-alpha line in an apparently faint galaxy at a redshift of 8.68, corresponding to a time when the universe should be full of absorbing hydrogen clouds,” said co-author and Caltech astronomer Richard Ellis. “Quite apart from breaking the earlier record redshift of 7.73, also obtained at the Keck Observatory, this detection is telling us something new about how the universe evolved in its first few hundred million years.”

Computer simulations of cosmic reionisation suggest the universe was fully opaque to Lyman-alpha radiation in the first 400 million years of cosmic history and then gradually, as the first galaxies were born, the intense ultraviolet radiation from their young stars, burned off this obscuring hydrogen in bubbles of increasing radius which, eventually, overlapped so the entire space between galaxies became ‘ionised,’ that is composed of free electrons and protons. At this point the Lyman-alpha radiation was free to travel through space unimpeded.

It may be that the galaxy we have observed, EGSY8p7, which is unusually (intrinsically) luminous, has special properties that enabled it to create a large bubble of ionised hydrogen much earlier than is possible for more typical galaxies at these times,” said Sirio Belli, a Caltech graduate student who helped undertake the key observations. “EGSY8p7 was found to be both luminous and at high redshift, and its colours measured by the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescope indicate it may be powered by a population of unusually hot stars.”

Because the discovery of such an early source with powerful Lyman-alpha is somewhat unexpected, it provides new insight into the manner by which galaxies contributed to the process of reionisation. Conceivably the process is patchy with some regions of space evolving faster than others, for example due to variations in the density of matter from place to place. Alternatively, EGSY8p7 may be the first example of an early generation which unusually strong ionising radiation.

“In some respects, the period of cosmic reionisation is the final missing piece in our overall understanding of the evolution of the universe,” says Zitrin. “In addition to pushing back the frontier to a time when the universe was only 600 million years old, what is exciting about the present discovery is that the study of sources such as EGSY8p7 will offer new insight into how this process occurred.”

The Caltech team reporting on this discovery consists of Zitrin, Ellis, and Belli who lead an international collaboration involving astronomers at Yale and the University of Arizona, and fellow European researchers from Leiden University in the Netherlands and the University of Durham and the University College London in England.