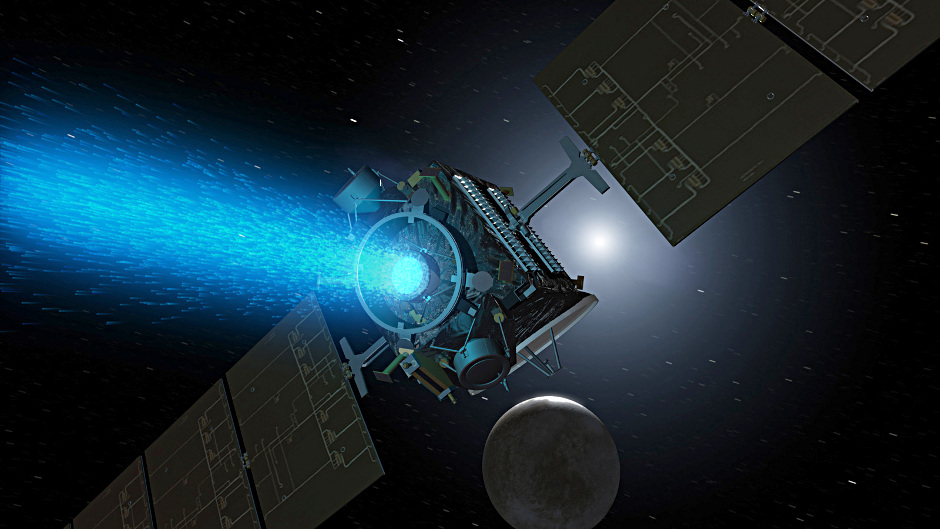

Dawn has been following its planned trajectory (http://dawnblog.jpl.nasa.gov) on the dark side of Ceres — the side facing away from the Sun — since early March. After it entered orbit, the spacecraft’s momentum carried it to a higher altitude, reaching a maximum of 46,800 miles (75,400 kilometres) on March 18th. Dawn is currently about 26,000 miles (42,000 kilometres) above Ceres, descending toward the first planned science orbit, which will be 8,400 miles (13,500 kilometres) above the surface.

The next optical navigation images of Ceres will be taken on April 10th and April 14th, and are expected to be available online after initial analysis by the science team. In the first of these, the dwarf planet will appear as a thin crescent, much like the images taken on March 1st, but with about 1.5 times higher resolution. The April 14th images will reveal a slightly larger crescent in even greater detail. Once Dawn settles into the first science orbit on April 23th, the spacecraft will begin the intensive prime science campaign.

By early May, images will improve our view of the entire surface, including the mysterious bright spots that have captured the imaginations of scientists and space enthusiasts alike. What these reflections of sunlight represent is still unknown, but closer views should help determine their nature. The regions containing the bright spots will likely not be in view for the April 10th images; it is not yet certain whether they will be in view for the April 14th set.

On May 9th, Dawn will complete its first Ceres science phase and begin to spiral down to a lower orbit to observe Ceres from a closer vantage point.

Dawn previously explored the giant asteroid Vesta for 14 months, from 2011 to 2012, capturing detailed images and data about that body.