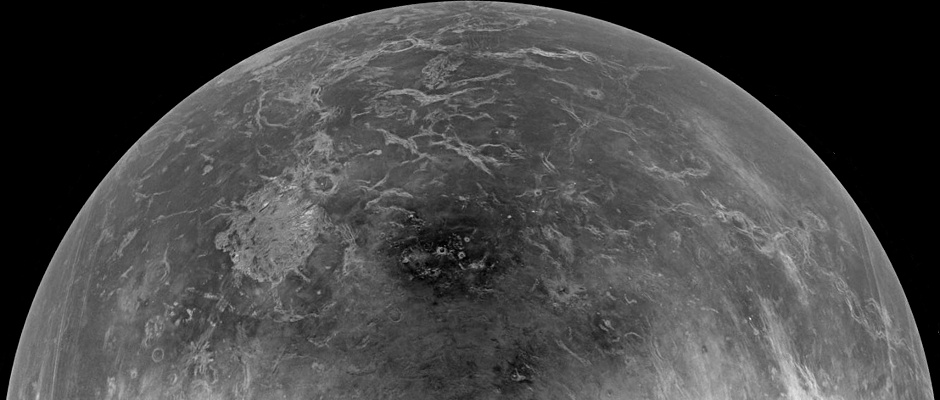

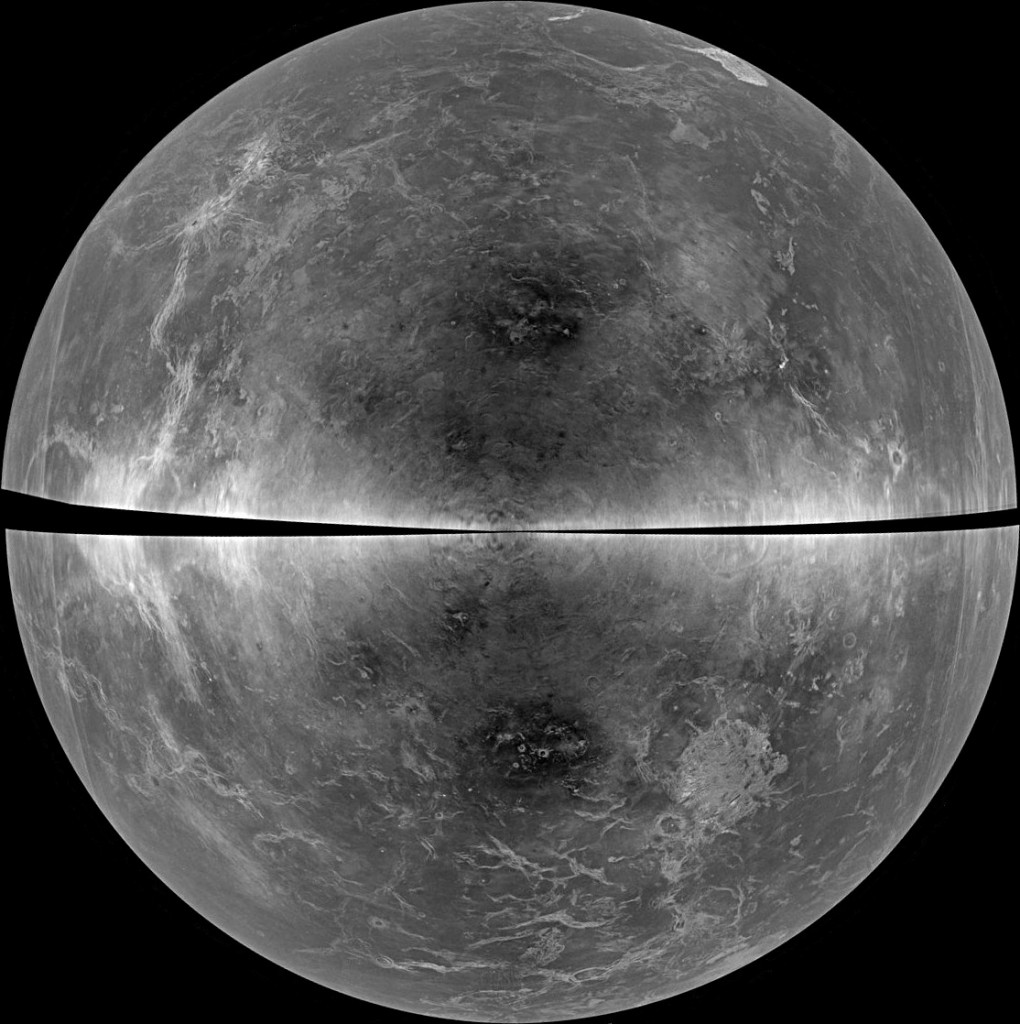

Recently, by combining the highly sensitive receiving capabilities of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Green Bank Telescope (GBT) and the powerful radar transmitter at the NSF’s Arecibo Observatory, astronomers were able to make remarkably detailed images of the surface of this planet without ever leaving Earth.

The radar signals from Arecibo passed through both our planet’s atmosphere and the atmosphere of Venus, where they hit the surface and bounced back to be received by the GBT in a process known as bistatic radar.

This capability is essential to study not only the surface as it appears now, but also to monitor it for changes. By comparing images taken at different periods in time, scientists hope to eventually detect signs of active volcanism or other dynamic geologic processes that could reveal clues to Venus’s geologic history and subsurface conditions.

“It is painstaking to compare radar images to search for evidence of change, but the work is ongoing. In the meantime, combining images from this and an earlier observing period is yielding a wealth of insight about other processes that alter the surface of Venus,” said Bruce Campbell, Senior Scientist with the Center for Earth and Planetary Studies at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. A paper discussing the comparison between these two observations was accepted for publication in the journal Icarus.

The 100-metre Green Bank Telescope is the world’s largest fully steerable radio telescope. Its location in the National Radio Quiet Zone and the West Virginia Radio Astronomy Zone protects the incredibly sensitive telescope from unwanted radio interference, enabling it to perform unique observations.