UMD astronomers Michael A’Hearn and Dennis Bodewits co-authored three of the papers, as members of the team for Rosetta’s Optical, Spectroscopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS). This trio of papers helps us to better understand how comets form in the first place, how their surfaces evolve over time and how to (potentially) predict their lifespans.

“We are trying to see how a comet evolves over time, and also through the course of its orbit. Gaining this detailed time series is what distinguishes Rosetta from other missions, such as Deep Impact,” said A’Hearn, a Distinguished University Professor Emeritus of astronomy at UMD. A’Hearn served as principal investigator on the Deep Impact mission, which sent an impactor module to the surface of comet Tempel I in 2005. This mission was the first to remove material from the interior of a comet’s nucleus — the solid central lump of ice, dust and debris — and compare it to the material at the surface.

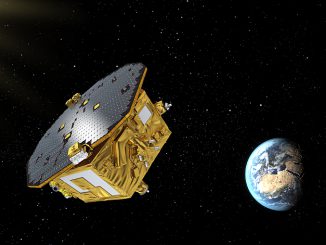

The versatile OSIRIS imager consists of two cameras, each with its own set of specialised filters. The narrow angle camera is designed to image the surface of the comet’s nucleus, while the wide angle camera focuses on the cloud of gas and dust around it.

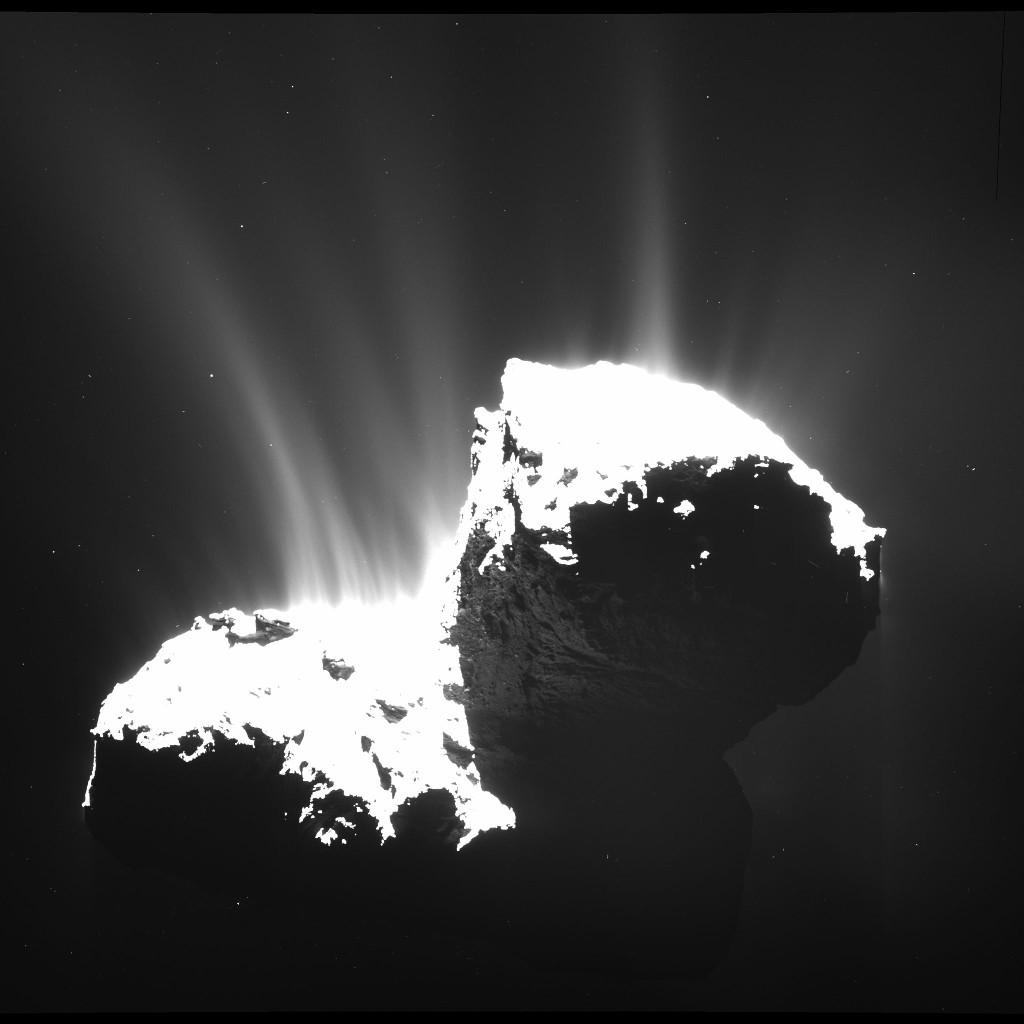

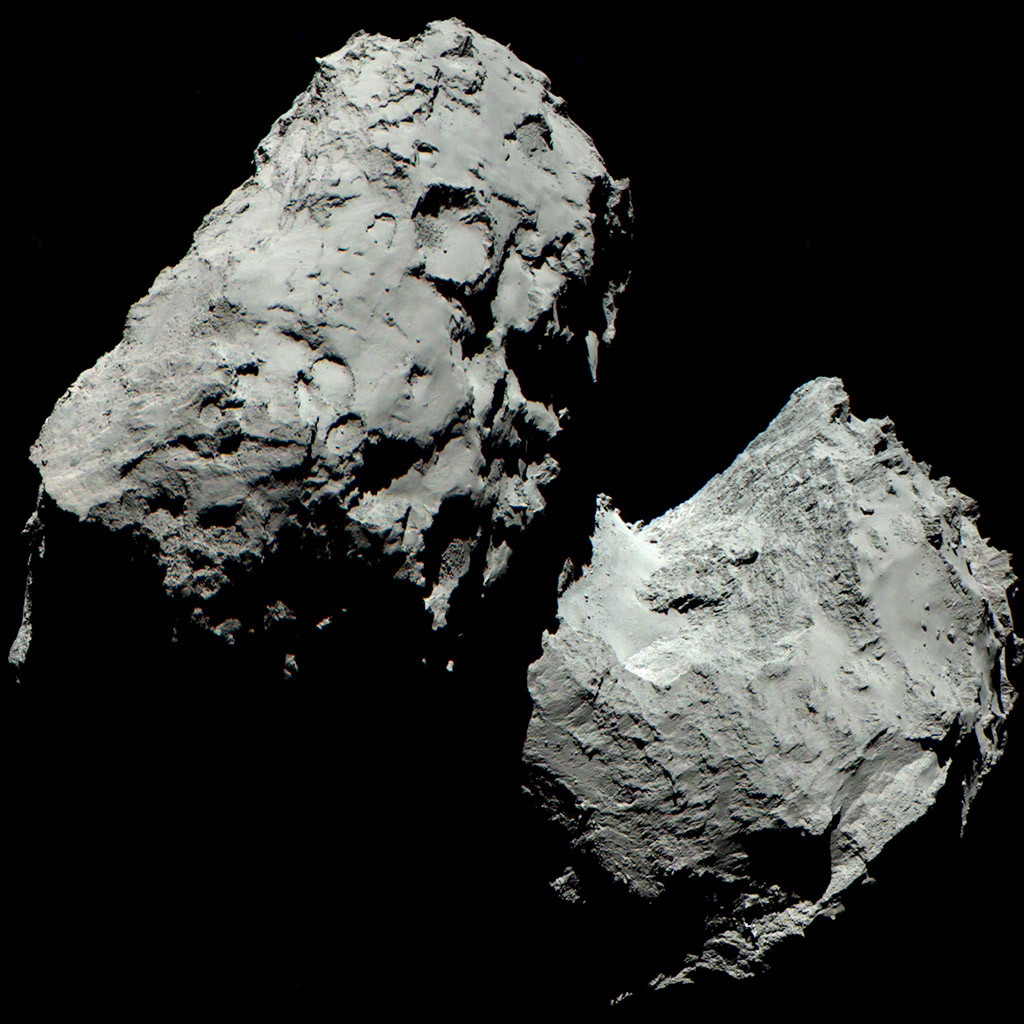

One of the Rosetta papers uses OSIRIS images to analyse the structure of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, known to the mission team simply as C-G. Described as roughly the shape of a rubber duck, it consists of two lobes connected by a thin “neck.” The team found that the majority of outgassing activity from the comet is occurring at the neck, where the OSIRIS cameras have consistently seen jets of gas and debris. The finding raises questions as to whether C-G formed from the combination of two smaller bodies, or began as one large body that shrank around the middle, like an apple that has been eaten around its core.

“Comets are effectively twice as black as coal, with a thick dust layer shrouding the surface,” said Bodewits, an assistant research scientist at UMD. “It’s important to look for sublimating gas. This is where there are cracks in the dust layer, which can help us find water ice and track small changes in the comet’s surface.”

A third paper combines data from OSIRIS and another instrument, the Grain Impact Analyser and Dust Accumulator (GIADA). This study looks at C-G’s coma — the thick cloud of dust and gas that envelops the nucleus. As the comet gets closer to the Sun, the coma grows more massive as the nucleus heats up and loses more material. By measuring the activity in the coma, including changes in the ratio of dust to gas, the team should be able to estimate how quickly C-G is outgassing and losing mass. In so doing, the team hopes to learn more about how comets evolve.

“Because comets have very little gravity, dust and gas flow freely into space. But we were surprised to find a cloud of particles orbiting the comet that are large and heavy enough to defy the Sun’s radiation pressure,” Bodewits said. The team was able to make this discovery thanks to OSIRIS’ very sensitive cameras. “Each pixel is about 30 centimetres. You couldn’t see a coffee cup, but you could see a large lunchbox. The resolution is about 10 times higher than Google Earth.”

A’Hearn and Bodewits are particularly excited for further developments, as C-G and Rosetta hurtle ever closer to the Sun. The comet will be most active when it reaches perihelion, or the single point in C-G’s orbit that is the closest and most intensely affected by solar radiation. It will reach this point on 13th August 2015, after which it will head away from the Sun once again.

“We are already seeing more activity. Jets are sprouting up everywhere,” Bodewits said. “We’ve been surprised to see how active it is. It already has more jets than many other comets do at perihelion.”

A fourth paper is co-authored by Murthy Gudipati, a part-time senior research scientist at the UMD Institute for Physical Science and Technology. This study describes evidence for carbon-based molecules on C-G’s surface, gathered by Rosetta’s Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) instrument.

Based on past comet studies, the team expected to see signatures of slightly more complex molecules such as alcohols, carboxylic acids and nitrogen-containing amines. However, the evidence from VIRTIS suggests that C-G’s surface is instead dominated by simpler hydrocarbons. The discovery could have implications for our understanding of how carbon-based molecules first developed and spread through our solar system.

“Comets have always surprised humanity,” Gudipati said. “C-G seems to be no exception.”