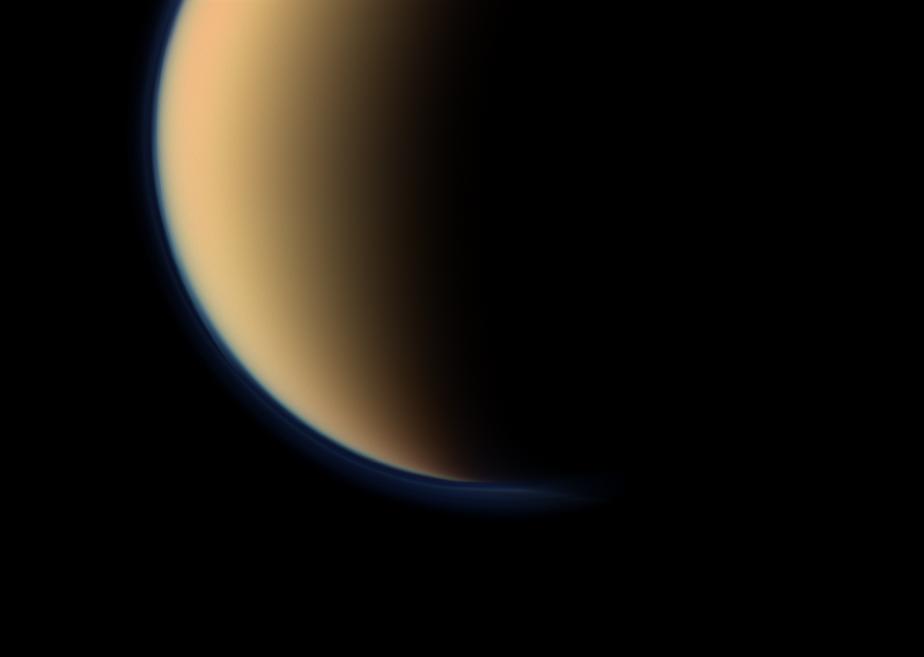

This near-infrared, colour mosaic from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows the sun glinting off of Titan’s north polar seas. While Cassini has captured, separately, views of the polar seas and the sun glinting off of them in the past, this is the first time both have been seen together in the same view.

The sunglint, also called a specular reflection, is the bright area near the 11 o’clock position at upper left. This mirror-like reflection, known as the specular point, is in the south of Titan’s largest sea, Kraken Mare, just north of an island archipelago separating two separate parts of the sea.

This particular sunglint was so bright as to saturate the detector of Cassini’s Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) instrument, which captures the view. It is also the sunglint seen with the highest observation elevation so far — the sun was a full 40 degrees above the horizon as seen from Kraken Mare at this time — much higher than the 22 degrees seen earlier. Because it was so bright, this glint was visible through the haze at much lower wavelengths than before, down to 1.3 microns.

The southern portion of Kraken Mare (the area surrounding the specular feature toward upper left) displays a “bathtub ring” — a bright margin of evaporate deposits — which indicates that the sea was larger at some point in the past and has become smaller due to evaporation. The deposits are material left behind after the methane & ethane liquid evaporates, somewhat akin to the saline crust on a salt flat.

The highest resolution data from this flyby — the area seen immediately to the right of the sunglint — cover the labyrinth of channels that connect Kraken Mare to another large sea, Ligeia Mare. Ligeia Mare itself is partially covered in its northern reaches by a bright, arrow-shaped complex of clouds. The clouds are made of liquid methane droplets, and could be actively refilling the lakes with rainfall.

The view was acquired during Cassini’s August 21, 2014, flyby of Titan, also referred to as “T104” by the Cassini team.

The view contains real colour information, although it is not the natural colour the human eye would see. Here, red in the image corresponds to 5.0 microns, green to 2.0 microns, and blue to 1.3 microns. These wavelengths correspond to atmospheric windows through which Titan’s surface is visible. The unaided human eye would see nothing but haze.