Striking 3-D detail highlights a towering mountain, the brightest spots and other features on dwarf planet Ceres in a new video from NASA’s Dawn mission.

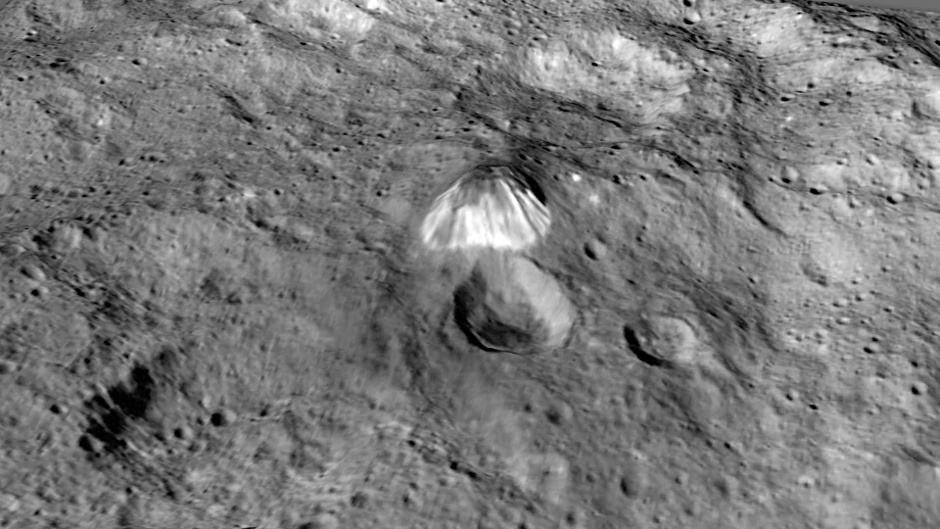

A prominent mountain with bright streaks on its steep slopes is especially fascinating to scientists. The peak’s shape has been likened to a cone or a pyramid. It appears to be about 4 miles (6 kilometres) high, with respect to the surface around it, according to the latest estimates. This means the mountain has about the same elevation as Mount McKinley in Denali National Park, Alaska, the highest point in North America.

“This mountain is among the tallest features we’ve seen on Ceres to date,” said Dawn science team member Paul Schenk, a geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. “It’s unusual that it’s not associated with a crater. Why is it sitting in the middle of nowhere? We don’t know yet, but we may find out with closer observations.”

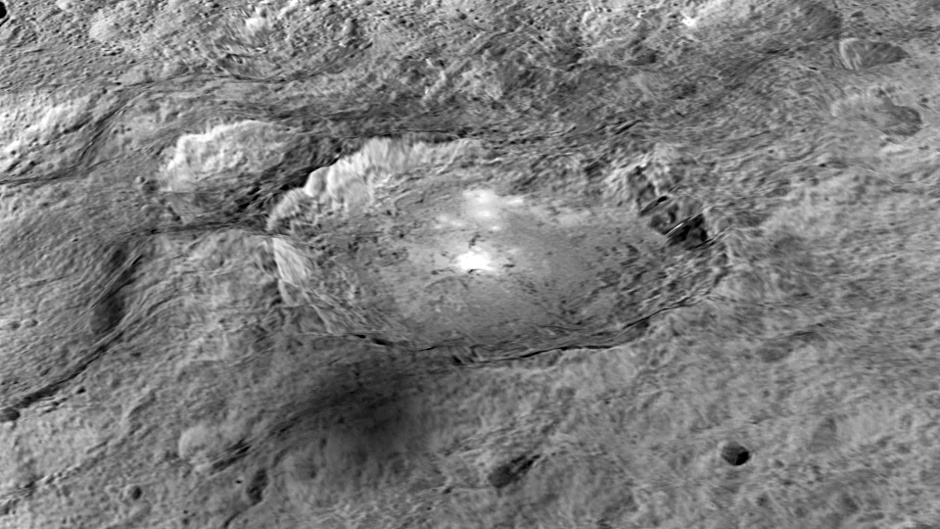

In examining the way Occator’s bright spots reflect light at different wavelengths, the Dawn science team has not found evidence that is consistent with ice. The spots’ albedo — a measure of the amount of light reflected — is also lower than predictions for concentrations of ice at the surface.

An animation of Ceres’ overall geography, also available in 3-D, shows these features in context. Occator lies in the northern hemisphere, whereas the tall mountain is farther to the southeast (11 degrees south, 316 degrees east).

“There are many other features that we are interested in studying further,” said Dawn science team member David O’Brien, with the Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona. “These include a pair of large impact basins called Urvara and Yalode in the southern hemisphere, which have numerous cracks extending away from them, and the large impact basin Kerwan, whose centre is just south of the equator.”

Ceres is the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Thanks to data acquired by Dawn since the spacecraft arrived in orbit at Ceres, scientists have revised their original estimate of Ceres’ average diameter to 584 miles (940 kilometres). The previous estimate was 590 miles (950 kilometres).

Dawn will resume its observations of Ceres in mid-August from an altitude of 900 miles (less than 1,500 kilometres), or three times closer to Ceres than its previous orbit.

On 6 March 2015, Dawn made history as the first mission to reach a dwarf planet, and the first to orbit two distinct extraterrestrial targets. It conducted extensive observations of Vesta in 2011-2012.