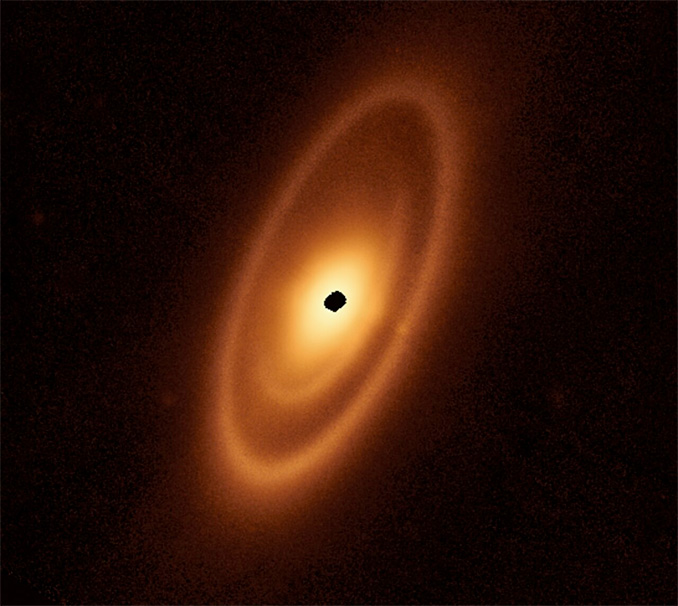

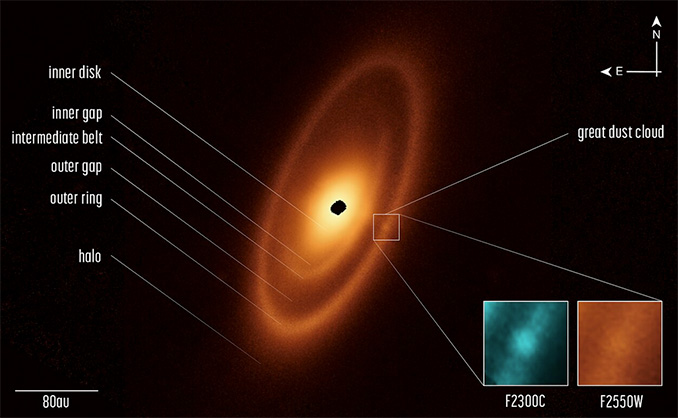

In another dramatic demonstration of the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared prowess, astronomers have found three nested rings of dusty debris around the bright young star Fomalhaut, the apparent result of gravitational interactions of unseen planets within the asteroid belt-like structures.

“The belts around Fomalhaut are kind of a mystery novel: Where are the planets?” said George Rieke, a member of the research team and the U.S. science lead for Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). “I think it’s not a very big leap to say there’s probably a really interesting planetary system around the star.”

The researchers had been expecting to study a single debris ring discovered in 1983 by NASA’s Infrared Astronomy Satellite, a vast belt of cool, dusty material circling Fomalhaut at distances ranging out to 23 billion kilometres (14 billion miles). The belt is roughly twice the size of the Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune.

But Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument found two more inner rings of debris separated by gaps indicative of the gravitational effects of unseen planets sweeping out the area around them. MIRI also detected a concentration of material in the outermost ring that may have been generated by a protoplanetary collision. It’s been dubbed “the great dust cloud.”

“Where Webb really excels is that we’re able to physically resolve the thermal glow from dust in those inner regions,” said Schuyler Wolff, a team member at the University of Arizona. “So you can see inner belts that we could never see before.”

He said the team did not expect “the more complex structure with the second intermediate belt and then the broader asteroid belt. That structure is very exciting because any time an astronomer sees a gap and rings in a disc, they say, ‘there could be an embedded planet shaping the rings!’”

Debris discs like those around Fomalhaut are thought to be generated in the chaotic aftermath of planet formation as bodies impact and collide, creating huge clouds of pulverised rock, ice and other materials. The discs serve as signposts of sorts, indicating the presence of larger, unseen bodies

“I would describe Fomalhaut as the archetype of debris discs found elsewhere in our galaxy, because it has components similar to those we have in our own planetary system,” said András Gáspár of the University of Arizona in Tucson, lead author of a paper describing the observations in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“By looking at the patterns in these rings, we can actually start to make a little sketch of what a planetary system ought to look like — if we could actually take a deep enough picture to see the suspected planets.”