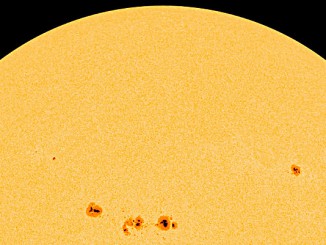

When stars like the Sun begin running out of nuclear fuel, they can become red giants, swelling in size and consuming any nearby planets. That’s the fate that awaits Mercury, Venus and possibly Earth in about 5 billion years as a bloated Sun, nearing the end of its life, expands beyond their orbits.

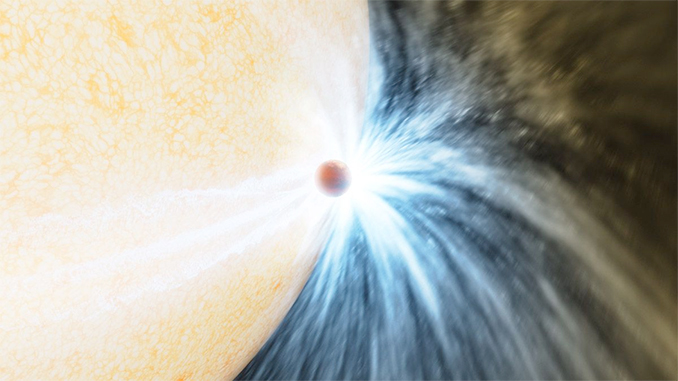

That’s the theory, anyway. But now, for the first time, astronomers have actually caught a star in the act of devouring a Jupiter-size planet in a solar system 15,000 light years away, brightening for about a week as it gorged.

“The confirmation that sun-like stars engulf inner planets provides us with a missing link in our understanding of the fates of solar systems, including our own,” said Kishalay De, a postdoctoral scholar at MIT and lead author of a study published in the journal Nature on 4 May – Star Wars Day.

The star was first spotted by the Zwicky Transient Facility, or ZTF, at Palomar Observatory near San Diego, California. De initially thought the star, known as ZTF SLRN-2020, might be a nova, but follow-up observations by the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii seemed to rule that out. The outburst was surrounded by a cooler material than expected.

“The Keck data indicated that the star was not lighting up hot gas as is expected for novae,” De said. “I couldn’t make any sense of it.”

Additional observations by the Hale Telescope at Palomar and then a review of data collected by NASA’s NEOWISE space telescope showed the star brightened in the infrared about nine months before the ZTF caught the rise in optical light.

“The infrared observations were one of the main clues that we were looking at a star engulfing a planet,” said Viraj Karambelkar, a graduate student at Caltech and co-author of the study.

The Near-Infrared Echellette Spectrograph at Keck confirmed a layer of cool gas and dust. The dust, the researchers concluded, was generated as a planet spiralled into the star’s bloated atmosphere.

“The planet plunged into the core of the star and got swallowed whole,” De said. “As it was doing this, energy was transferred to the star. The star blew off its outer layers to get rid of the energy. It expanded and brightened, and the brightening is what ZTF registered.”

The observations were “just spectacular,” said co-author Mansi Kasliwal, professor of astronomy at Caltech and a co-investigator on the ZTF project.

“We are still amazed that we caught a star in the act of ingesting its planet, something our own Sun will do to its inner planets,” he said. “Though that’s a long time from now, in five billion years, so we don’t have to worry just yet.”