The annual spectacular which is the Perseid meteor shower returns to a predicted peak on the night of 12/13 August (Friday night/Saturday morning) between 2am to 5am BST (01h–04h UT). Unfortunately, this year’s maximum will be seriously affected by the very unwelcome glow from a near-full Moon (at full phase on 12 August at 01:36 UT, the night before the anticipated Perseid maximum). Nevertheless, it should still be possible to witness some of the shower’s frequently bright meteors, with the occasional very bright shooting star called a fireball, that the Perseids can be relied upon to produce. They often leave persistent trains, or trails across the sky.

Each meteor shower is linked with a ‘parent comet’, with periodic comet 109P/Swift–Tuttle being associated with the Perseids. Cometary material is shed at each return it makes to the inner Solar System. This debris is spread out along 109P/Swift–Tuttle’s orbital path and when Earth intersects this stream of particles then a number of them enter our upper atmosphere, vaporising to form the streaks of light we see as meteors.

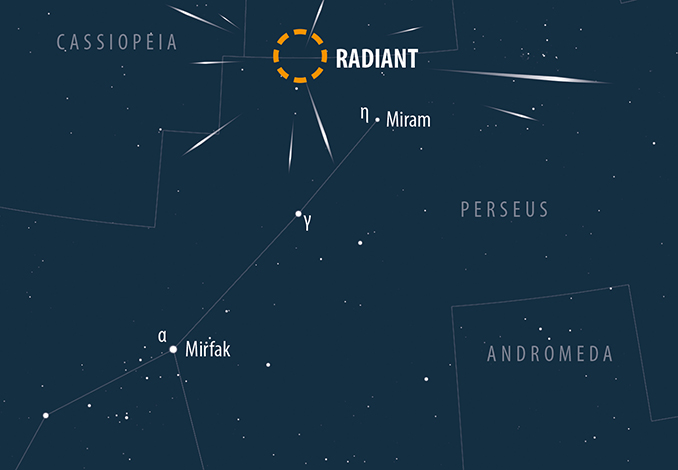

Perseid meteors can be traced back to a point in the called astronomer’s call the radiant. It lies in the far north of Perseus (see the graphic), around 2.5 degrees north-east of magnitude +3.8 Miram (eta Persei), not far east from the spectacular double cluster in northern Perseus. The radiant lies low in the north-eastern sky as darkness falls, climbing to a decent altitude of 50 degrees or so by 2am BST, a timing which corresponds nicely with the predicted Perseid peak.

At its best, the Perseids can produce 50–70 meteors per hour close to its maximum. In towns or cities, observed rates may still be around ten per hour in the early-morning hours when the radiant is high, though moonlight will swamp the fainter meteors wherever you are observing.