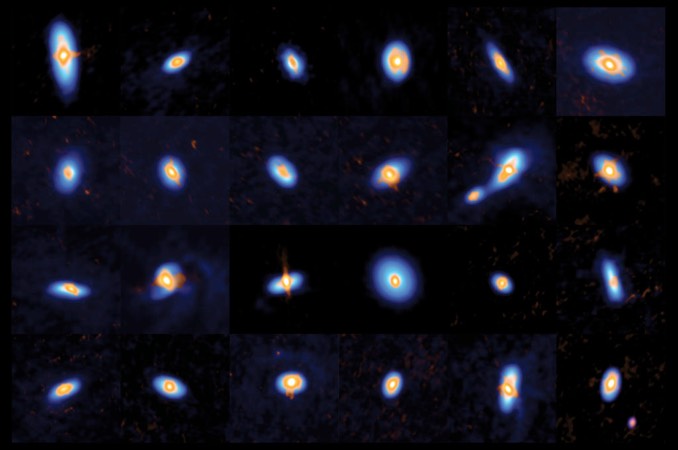

Most of the stars in the universe are accompanied by planets. These planets are born in rings of dust and gas, called protoplanetary disks. Even very young stars are surrounded by these disks. Astronomers want to know exactly when these disks start to form, and what they look like. But young stars are very faint, and there are dense clouds of dust and gas surrounding them in stellar nurseries. Only highly sensitive radio telescope arrays can spot the tiny disks around these infant stars amidst the densely packed material in these clouds.

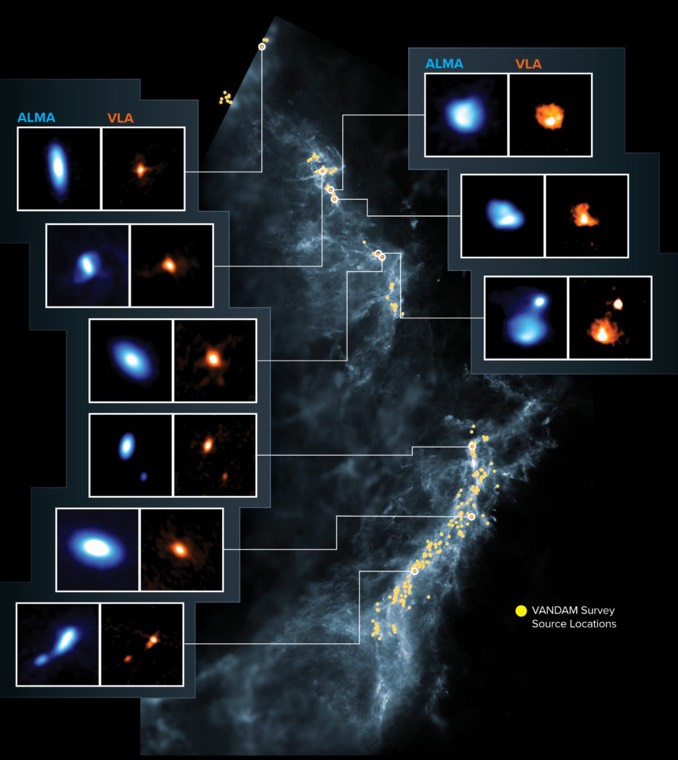

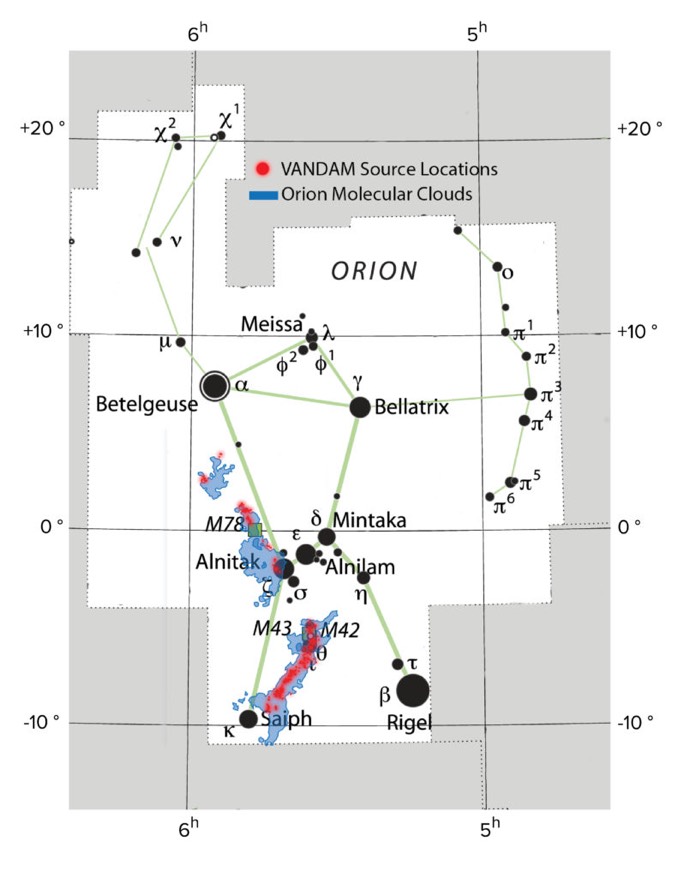

For this new research, astronomers pointed both the National Science Foundation’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) and the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) to a region in space where many stars are born: the Orion Molecular Clouds. This survey, called VLA/ALMA Nascent Disk and Multiplicity (VANDAM), is the largest survey of young stars and their disks to date.

Very young stars, also called protostars, form in clouds of gas and dust in space. The first step in the formation of a star is when these dense clouds collapse due to gravity. As the cloud collapses, it begins to spin – forming a flattened disk around the protostar. Material from the disk continues to feed the star and make it grow. Eventually, the left-over material in the disk is expected to form planets.

Many aspects about these first stages of star formation, and how the disk forms, are still unclear. But this new survey provides some missing clues as the VLA and ALMA peered through the dense clouds and observed hundreds of protostars and their disks in various stages of their formation.

“This survey revealed the average mass and size of these very young protoplanetary disks,” said John Tobin of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) in Charlottesville, Virginia, and leader of the survey team. “We can now compare them to older disks that have been studied intensively with ALMA as well.”

What Tobin and his team found is that very young disks can be similar in size, but are on average much more massive than older disks. “When a star grows, it eats away more and more material from the disk. This means that younger disks have a lot more raw material from which planets could form. Possibly bigger planets already start to form around very young stars.”

The Orion Molecular Clouds, shown in blue, with the locations of protostars observed in the VANDAM survey shown in red. Image: IAU; Sky & Telescope magazine; NRAO/AUI/NSF, S. Dagnello; Herschel/ESA; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), J. Tobin

Among hundreds of survey images, four protostars looked different than the rest and caught the scientists’ attention.

“These newborn stars looked very irregular and blobby,” said team member Nicole Karnath of the University of Toledo, Ohio (now at SOFIA Science Center). “We think that they are in one of the earliest stages of star formation and some may not even have formed into protostars yet.”

To be defined as a typical (class 0) protostar, stars should not only have a flattened rotating disk surrounding them, but also an outflow – spewing away material in opposite directions – that clears the dense cloud surrounding the stars and makes them optically visible. This outflow is important because it prevents stars from spinning out of control while they grow. But when exactly these outflows start to happen, is an open question in astronomy.

The exquisite resolution and sensitivity provided by both ALMA and the VLA were crucial to understand both the outer and inner regions of protostars and their disks in this survey. While ALMA can examine the dense dusty material around protostars in great detail, the images from the VLA made at longer wavelengths were essential to understand the inner structures of the youngest protostars at scales smaller than our solar system.