Some 3.5 billion years ago, ponds fed by streams in the walls of Gale Crater likely went through cycles as the waterways flowed, dried up and then flowed again over millions of years during the planet’s transition from a warmer, wetter world to the frozen desert seen today.

In a paper published by Nature Geoscience, researchers with the Mars Curiosity rover interpret rocks laced with mineral sals as signs of shallow, briny ponds that went through episodic filling and drying. That may be the result of climate fluctuations occurring as the martian environment made that transition.

Finding out when and why it occurred are major objectives when it comes to deciphering the history of Mars.

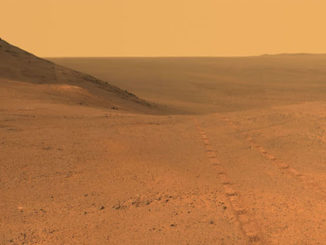

Curiosity landed on the floor of Gale Crater in 2012 and is slowly making its way up the lower slopes of Mount Sharp, a towering mound of sedimentary rock and soil at the heart of the 150-kilometre-wide (100-mile-wide) impact crater.

Data collected from orbit indicate rock in the lower regions of the mountain formed in a climate that may have been habitable in the remote past. Rocks in the higher regions appear to represent a much drier climate. Curiosity may help pinpoint when that transition occurred as it continues its trek up the slopes.

“We went to Gale Crater because it preserves this unique record of a changing Mars,” said lead author William Rapin of Caltech. “Understanding when and how the planet’s climate started evolving is a piece of another puzzle: When and how long was Mars capable of supporting microbial life at the surface?”

Rapin and his colleagues discuss salts found in a 150-metre-tall (500-foot-tall) formation known as Sutton Island that was studied by Curiosity in 2017. The salts suggest water that once pooled in the area was concentrated into brine, possibly crystallising just beneath evaporating ponds of briny water.

Similar saline lakes and ponds can be found on Earth in South America’s high-altitude Altiplano plain, fed by rivers and streams flowing from nearby mountains in the Andes.

“During drier periods, the Altiplano lakes become shallower, and some can dry out completely,” Rapin said. “The fact that they’re vegetation-free even makes them look a little like Mars.”

Curiosity is currently heading toward a region known as the “sulphate-bearing unit” that likely formed in a much drier environment, starkly different from lower regions where the rover found sediments indicating the past presence of fresh-water lakes.

“As we climb Mount Sharp, we see an overall trend from a wet landscape to a drier one,” said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “But that trend didn’t necessarily occur in a linear fashion. More likely, it was messy, including drier periods, like what we’re seeing at Sutton Island, followed by wetter periods, like what we’re seeing in the ‘clay-bearing unit’ that Curiosity is exploring today.”