As explained in an earlier observing story, around half of the stars in the vicinity of our Sun that appear singular to the naked eye are actually members of double or multiple systems when viewed through a telescope. Two gravitationally-bound stars, each orbiting their common centre of gravity, is termed a binary pair, whereas an optical double or triple is due to the chance alignment of a nearby star with one or more unrelated stars at differing distances.

This time we’re going to visit some interesting doubles in the prominent springtime constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman. (Click here for a printable PDF star chart clearly showing all the objects that follow.) Your launching point for any study of this star group is its brightest star, Arcturus, which may be found highest in the southern sky of the British Isles and Western Europe around 1am local time at the beginning of May, or by 11pm at the end of the month.

For some of the close doubles that follow, you will need a night when the seeing is good to see them clearly resolved. Also, do bear in mind that some of the colours are subtle and subjective. Colour perception varies from person to person and it also varies with age.

α = 14h 45.0m, δ = +27° 04’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +2.9 & +4.9

Separation: 2.9 arcseconds

Commonly known as Izar, epsilon (ε) Boötis is a fine double star with contrasting colours that lies 10.4 degrees northeast of Arcturus. Izar was recognised as a double by German-Russian astronomer F. G. W. Struve, who even went so far as to call it ‘Pulcherrima’, meaning ‘the most beautiful’. Best seen with at least a 7.6-cm (3-inch) aperture telescope at around 175× owing to the 2.9 arcsecond separation, the magnitude +2.9 primary is golden yellow, while the magnitude +4.9 companion is greenish. The orbital period of Epsilon Boötis is well over 1,000 years and its distance from Earth is about 200 light-years.

α = 14h 51.4m, δ = +19° 06’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +4.7 & +7.0

Separation: 5.3 arcseconds

Our next binary star, Xi (ξ) Boötis, lies some 8 degrees to the south of Izar. Of all the naked-eye stars in Boötes, Xi Boötis is the closest at just just under 22 light-years. Its yellowish G-type primary is slightly variable from +4.52 to +4.67 over a ten-day period, while the K-type companion appears reddish. The pair orbit their common centre of gravity every 152 years with a current separation of 5.3 arcseconds. Telescopes of 10- to 15-cm (4- to 6-inch) aperture resolve this binary nicely at magnifications of 100× or more.

α = 14h 40.7m, δ = +16° 25’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +4.9 & +5.8

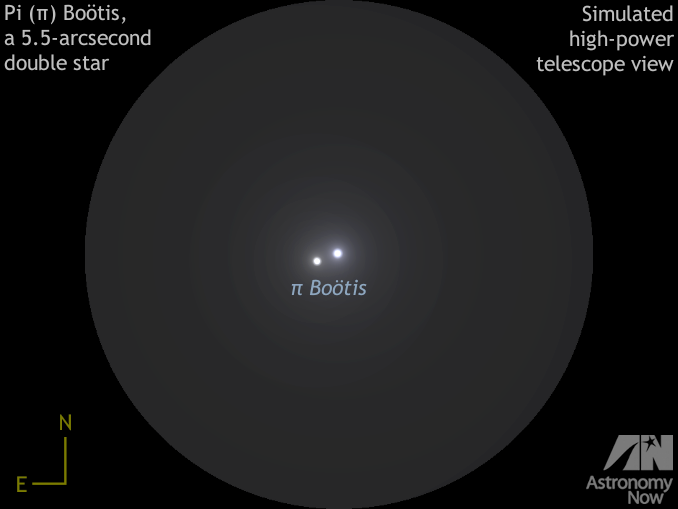

Separation: 5.5 arcseconds

Move your telescope 3⅔ degrees to the southeast of ξ Boötis and you’ll arrive at pi (π) Boötis. This is a fine pair of white stars (though some see the primary as pale bluish) separated by 5½ arcseconds, so a telescope magnification of 100× or more is required. The system lies about 320 light-years from us.

α = 14h 16.5m, δ = +20° 07’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +6.5 & +8.2

Separation: 4.4 arcseconds

Our next port of call, Σ1825, is a sixth magnitude double that lies just one degree north of Arcturus. A binary system with an orbital period of 957 years, an eighth magnitude orange companion lies 4.4 arcseconds from a sixth magnitude yellow primary star. The pair are 106 light-years from Earth.

We now take a trek to northern Boötes about one and a half spans of an outstretched hand at arm’s length above Arcturus, an area near the tail of the Great Bear that is almost overhead as seen from the British Isles when best placed for observation.

α = 14h 13.5m, δ = +51° 47’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +4.6 & +6.6

Separation: 13.7 arcseconds

Our first target is Kappa (κ) Boötis, a double star with the intriguing proper name of Asellus Tertius, Latin for the ‘third donkey’. The other two donkeys are represented by Iota (ι) Boötis, aka Asellus Secundus, and Theta (θ) Boötis, or Asellus Primus. Kappa Boötis is a fine double for small telescopes as a magnification of just 75× reveals a magnitude +4.6 white primary with a magnitude +6.6 bluish companion 13.7 arcseconds away. Their distance from Earth is about 155 light-years.

Iota (ι) Boötis aka ‘Asellus Secundus‘

α = 14h 16.2m, δ = +51° 22’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +4.9 & +7.5

Separation: 39 arcseconds

Little more than the width of the full Moon to the southeast of Kappa Boötis is where you’ll find Iota (ι) Boötis, hence Kappa and Iota will fit in the same field of view of typical eyepieces delivering a magnification of 70× or less. At this sort of power you can see that Iota Boötis is a nice wide double star with a yellowish primary and a bluish companion separated by 39 arcseconds, which is about the same as the angular width of Jupiter.

α = 14h 49.7m, δ = +48° 43’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +6.2 & +6.9

Separation: 2.6 arcseconds

Move your telescope five degrees to the southeast of Theta (θ) Boötis and you’ll arrive at the fifth magnitude double star 39 Boötis. You’ll need a night of good seeing and at least a 10-cm (4-inch) telescope at magnifications of around 150× to comfortably split it into a yellow pair just 2.6 arcseconds apart. The orbital period of 39 Boötis is yet to be determined, but the stars lie 224 light-years from us.

α = 15h 24.5m, δ = +37° 23’ (J2000.0)

Magnitudes: +4.3, +7.0 & +7.6

Separation: 109 & 2.2 arcseconds

Last, but by no means least, a treat for you in the form of a triple star. Mu1 (μ1) Boötis has the wonderful proper name of Alkalurops, which is Greek for ‘club’. At low magnifications, the magnitude +4.6 yellow primary lies an easy 1.8 arcminutes from a seventh magnitude companion (μ2) to the south. Look closely at the latter with a 10-cm (4-inch) telescope or larger at a power of 150× or more and you’ll see it split into a yellowish orange pair just 2.2 arcseconds apart. This wonderful triple system lies about 115 light-years from Earth.

For accurate depictions of some of the star systems described above as seen through typical telescopes, I invite you to look at the wonderful sketches of talented astro-artist Jeremy Perez.