The farthest object ever explored is slowly revealing its secrets, as scientists piece together the puzzles of Ultima Thule – the Kuiper Belt object NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft flew past on New Year’s Day, four billion miles from Earth.

Analysing the data New Horizons has been sending home since the flyby of Ultima Thule (officially named 2014 MU69), mission scientists are learning more about the development, geology and composition of this ancient relic of solar system formation. The team discussed those findings (18 March) at the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

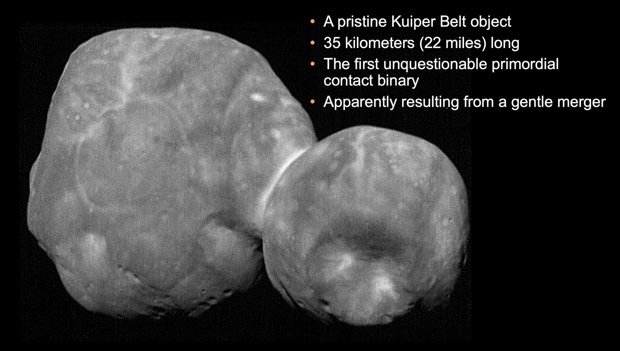

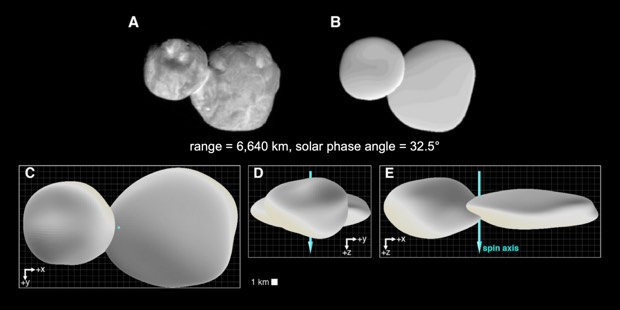

Ultima Thule is the first unquestionably primordial contact binary ever explored. Approach pictures of Ultima Thule hinted at a strange, snowman-like shape for the binary, but further analysis of images, taken near closest approach – New Horizons came to within just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometres) – have uncovered just how unusual the KBO’s shape really is. At 22 miles (35 kilometres) long, Ultima Thule consists of a large, flat lobe (nicknamed “Ultima”) connected to a smaller, rounder lobe (nicknamed “Thule”).

This strange shape is the biggest surprise, so far, of the flyby. “We’ve never seen anything like this anywhere in the solar system,” said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. “It is sending the planetary science community back to the drawing board to understand how planetesimals – the building blocks of the planets – form.”

Because it is so well preserved, Ultima Thule is offering our clearest look back to the era of planetesimal accretion and the earliest stages of planetary formation. Apparently Ultima Thule’s two lobes once orbited each other, like many so-called binary worlds in the Kuiper Belt, until something brought them together in a “gentle” merger.

“This fits with general ideas of the beginning of our solar system,” said William McKinnon, a New Horizons co-investigator from Washington University in St. Louis. “Much of the orbital momentum of the Ultima Thule binary must have been drained away for them to come together like this. But we don’t know yet what processes were most important in making that happen.”

That merger may have left its mark on the surface. The “neck” connecting Ultima and Thule is reworked, and could indicate shearing as the lobes combined, said Kirby Runyon, a New Horizons science team member from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland.

Runyon and fellow team geologists are describing and trying to understand Ultima Thule’s many surface features, from bright spots and patches, to hills and troughs, to craters and pits. The craters, while at first glance look like impact craters, could have other origins. Some may be pit craters, where material drains into underground cracks, or a result of sublimation, where ice went directly from solid to gas and left pits in its place. The largest depression is a 5-mile-wide (8-kilometre-wide) feature the team has nicknamed Maryland crater. It could be an impact crater, or it could have formed in one of the other above-mentioned ways.

“We have our work cut out to understand Ultima Thule’s geology, that is for sure,” Runyon said.

In colour and composition, New Horizons data revealed that Ultima Thule resembles many other objects found in its region of the Kuiper Belt. Consistent with pre-flyby observations from the Hubble Telescope, Ultima Thule is very red – redder even than Pluto, which New Horizons flew past on the inner edge of the Kuiper Belt in 2015 – and about the same colour as many other so-called “cold classical” KBOs.

New Horizons scientists have also seen evidence for methanol, water ice and organic molecules on the surface. “The spectrum of Ultima Thule is similar to some of the most extreme objects we’ve seen in the outer solar system,” said Silvia Protopapa, a New Horizons co-investigator from SwRI. “So New Horizons is giving us an incredible opportunity to study one of these bodies up close.”