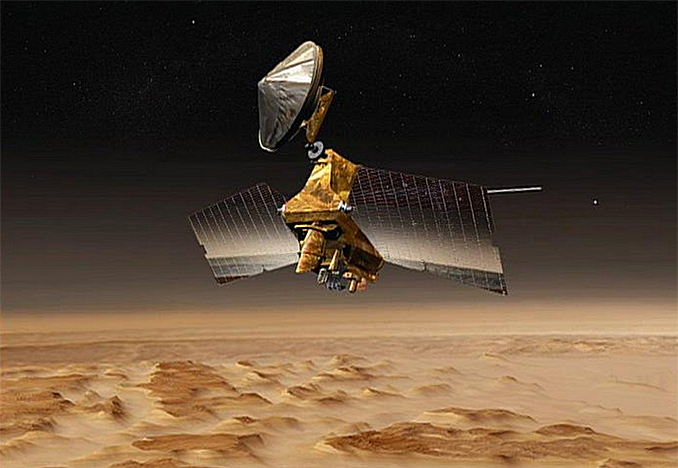

NASA is revising operating procedures to give the aging Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter a new lease on life.

Launched in 2005, the MRO remains fully operational, studying the red planet with a powerful camera and a suite of sophisticated sensors, and engineers want to make sure the satellite will remain healthy into the 2020s to continue basic exploration and to serve as a data relay station for future landers like NASA’s InSight and Mars 2020 rover.

“We know we’re a critical element for the Mars Program to support other missions for the long haul, so we’re finding ways to extend the spacecraft’s life,” Dan Johnston, the MRO project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a release. “In flight operations, our emphasis is on minimising risk to the spacecraft while carrying out an ambitious scientific and programmatic plan.”

One way to extend MROs life is to to extend the life of its two batteries, which power the spacecraft when it is in Mars’ shadow. Its current two-hour orbit includes about 40 minutes in darkness. Engineers are charging the batteries to higher levels than before to help extend their life and implementing procedures to reduce the overall power demand. Engineers also plan to tweak the MRO’s orbit after the upcoming rover landings to decrease the time spent in Mars’ shadow.

MRO’s attitude, or orientation, changes almost continuously as the satellite circles Mars, all the while keeping its instruments pointed in the desired direction. Two “inertial measurement units,” or IMUs, are on board that use built-in gyroscopes and accelerometers to help the flight computer keep track of the orbiter’s precise attitude. But the primary unit began showing signs of wear and tear after about 58,000 hours of operation, prompting the flight control team to switch to the spare unit.

The spare is still operating normally after more than 52,000 hours, but engineers want to minimise use of the mechanical devices, relying instead on the MRO’s star tracker system when possible. The star tracker uses a camera to pinpoint bright stars several times per second and pattern-recognition software allows the flight computer to figure out the spacecraft’s exact orientation with respect to those targets.

“In all-stellar mode, we can do normal science and normal relay,” Johnston said. “The inertial measurement unit powers back on only when it’s needed, such as … during critical events around a Mars landing” or to help the spacecraft recover after a fault. A key test of the “all stellar” mode was recently carried out and if all goes well, the technique will be implemented in for operational use in March.

Michael Meyer, lead scientist of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program at NASA Headquarters in Washington, said the agency is “counting on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter remaining in service for many more years.”

“It’s not just the communications relay that MRO provides, as important as that is,” he said. “It’s also the science-instrument observations. Those help us understand potential landing sites before they are visited, and interpret how the findings on the surface relate to the planet as a whole.”