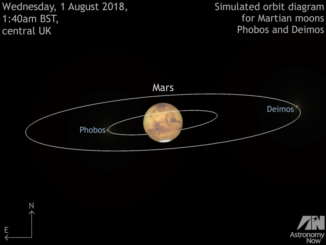

In one of these studies, a team of Belgian, French, and Japanese researchers offers, for the first time, a complete and coherent scenario for the formation of Phobos and Deimos, which would have been created following a collision between Mars and a primordial body one-third its size, 100 to 800 million years after the beginning of the planet’s formation. According to researchers, the debris from this collision formed a very wide disc around Mars, made up of a dense inner part composed of molten matter, and a very thin outer part primarily of gas. In the inner part of this disc formed a moon one thousand times the size of Phobos, which has since disappeared. The gravitational interactions created in the outer disc by this massive object apparently acted as a catalyst for the gathering of debris to form other smaller, more distant moons. After a few thousand years, Mars was surrounded by a group of approximately ten small moons and one enormous moon. A few million years later, once the debris disc had dissipated, the tidal effects of Mars brought most of these satellites back down onto the planet, including the very large moon. Only the two most distant small moons, Phobos and Deimos, remained.

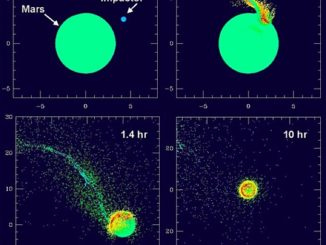

Due to the diversity of physical phenomena involved, no digital simulation is able to model the entire process. Pascal Rosenblatt and Sébastien Charnoz’s team thus had to combine three successive cutting-edge simulations in order to provide an account of the physics behind the giant collision, the dynamics of the debris resulting from the impact and its accretion to form satellites, and the long-term evolution of these satellites.

Yet the very small size of grains on the surface of Phobos and Deimos cannot, according to the researchers, be solely explained as the consequence of erosion from bombardment by interplanetary dust. This means that the satellites were from the beginning made up of very fine grains, which can only form by gas condensation in the outer area of the debris disc (and not from the magma present in the inner part). Both studies are in agreement on this point. Moreover, the formation of Martian moons from these very fine grains could also be responsible for a high internal porosity, which would explain their surprisingly low density.

The theory of the giant collision, which is corroborated by these two independent studies, could explain why the northern hemisphere of Mars has a lower altitude than the southern hemisphere: the Borealis basin is most probably the remains of a giant collision, such as the one that in time gave birth to Phobos and Deimos. It also helps explain why Mars has two satellites instead of a single one like our Moon, which was also created by a giant collision. This research suggests that the satellite systems that were created depended on the planet’s rotational velocity, because at the time Earth was rotating very quickly (in less than four hours), whereas Mars turned six times more slowly.

New observations will soon make it possible to know more about the age and composition of Martian moons. Japan’s space agency (JAXA) has decided to launch a mission in 2022, named Mars Moons Exploration (MMX), which will bring back samples from Phobos to Earth in 2027. Their analysis could confirm or invalidate this scenario. The European Space Agency (ESA) has planned a similar mission in 2024 in association with the Russian space agency (Roscosmos).