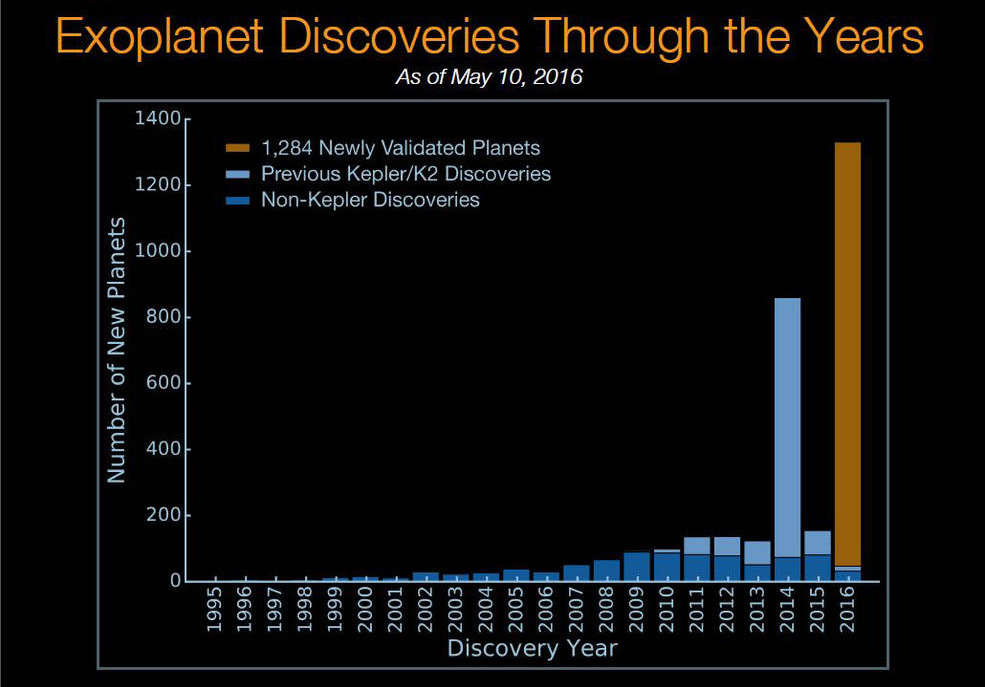

“This announcement more than doubles the number of confirmed planets from Kepler,” said Ellen Stofan, chief scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “This gives us hope that somewhere out there, around a star much like ours, we can eventually discover another Earth.”

Analysis was performed on the Kepler space telescope’s July 2015 planet candidate catalogue, which identified 4,302 potential planets. For 1,284 of the candidates, the probability of being a planet is greater than 99 percent — the minimum required to earn the status of “planet.” An additional 1,327 candidates are more likely than not to be actual planets, but they do not meet the 99 percent threshold and will require additional study. The remaining 707 are more likely to be some other astrophysical phenomena. This analysis also validated 984 candidates previously verified by other techniques.

“Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy. Thanks to Kepler and the research community, we now know there could be more planets than stars,” said Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters. “This knowledge informs the future missions that are needed to take us ever-closer to finding out whether we are alone in the universe.”

This latest announcement, however, is based on a statistical analysis method that can be applied to many planet candidates simultaneously. Timothy Morton, associate research scholar at Princeton University in New Jersey and lead author of the scientific paper published in The Astrophysical Journal, employed a technique to assign each Kepler candidate a planet-hood probability percentage — the first such automated computation on this scale, as previous statistical techniques focused only on sub-groups within the greater list of planet candidates identified by Kepler.

“Planet candidates can be thought of like bread crumbs,” said Morton. “If you drop a few large crumbs on the floor, you can pick them up one by one. But, if you spill a whole bag of tiny crumbs, you’re going to need a broom. This statistical analysis is our broom.”

“They say not to count our chickens before they’re hatched, but that’s exactly what these results allow us to do based on probabilities that each egg (candidate) will hatch into a chick (bona fide planet),” said Natalie Batalha, co-author of the paper and the Kepler mission scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California. “This work will help Kepler reach its full potential by yielding a deeper understanding of the number of stars that harbour potentially habitable, Earth-size planets — a number that’s needed to design future missions to search for habitable environments and living worlds.”

Of the nearly 5,000 total planet candidates found to date, more than 3,200 now have been verified, and 2,325 of these were discovered by Kepler. Launched in March 2009, Kepler is the first NASA mission to find potentially habitable Earth-size planets. For four years, Kepler monitored 150,000 stars in a single patch of sky, measuring the tiny, telltale dip in the brightness of a star that can be produced by a transiting planet. In 2018, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite will use the same method to monitor 200,000 bright nearby stars and search for planets, focusing on Earth and Super-Earth-sized.