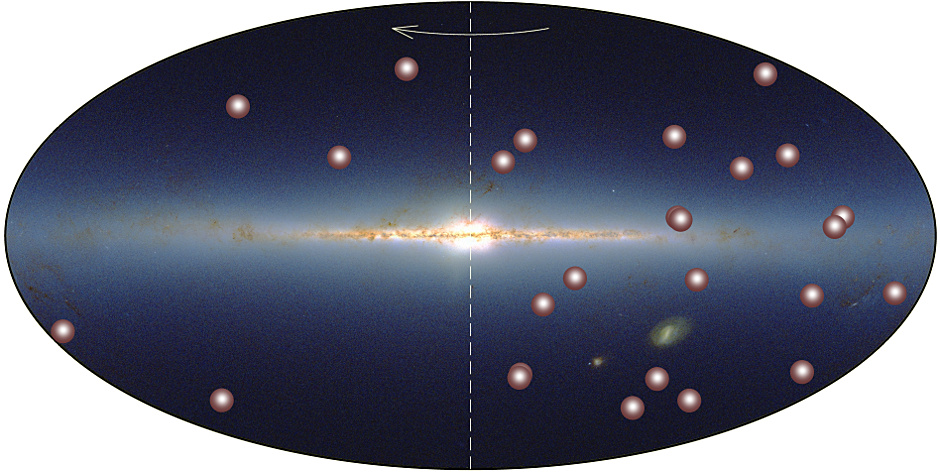

Gabriel Bihain and Ralf-Dieter Scholz from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) have taken a careful look at the distribution of nearby known brown dwarfs from a point of view that was not looked at before. To their surprise they discovered a significant asymmetry in the spatial configuration, strongly deviating from the known distribution of stars.

“I projected the nearby brown dwarfs onto the galactic plane and suddenly realised: half of the sky is practically empty! We absolutely didn’t expect this, as we have been looking at an environment that should be homogeneous,” Gabriel Bihain explained. Seen from Earth, the empty region overlaps with a large part of the northern sky.

The scientists concluded that there should be many more brown dwarfs in the solar neighbourhood that are yet to be discovered and that will fill the observed gap. If they are right, this would mean that star formation fails significantly more often than previously thought, producing one brown dwarf for every four stars. In any case, it appears, the established picture of the solar neighbourhood and of its brown dwarf population will have to be rethought.

“It is quite possible that not only brown dwarfs are still hiding in the observational data, but also other objects with even smaller, planetary-like masses. So it is definitely worth it to take another deep look at both existing and future data,” Ralf-Dieter Scholz concluded.

This research has just been published online in Astronomy & Astrophysics.