Scientists working on citizen science project Radio Galaxy Zoo developed an online tutorial to teach volunteers how to spot black holes and other objects that emit large amounts of energy through radio waves.

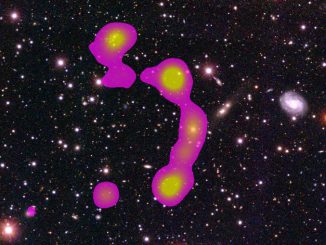

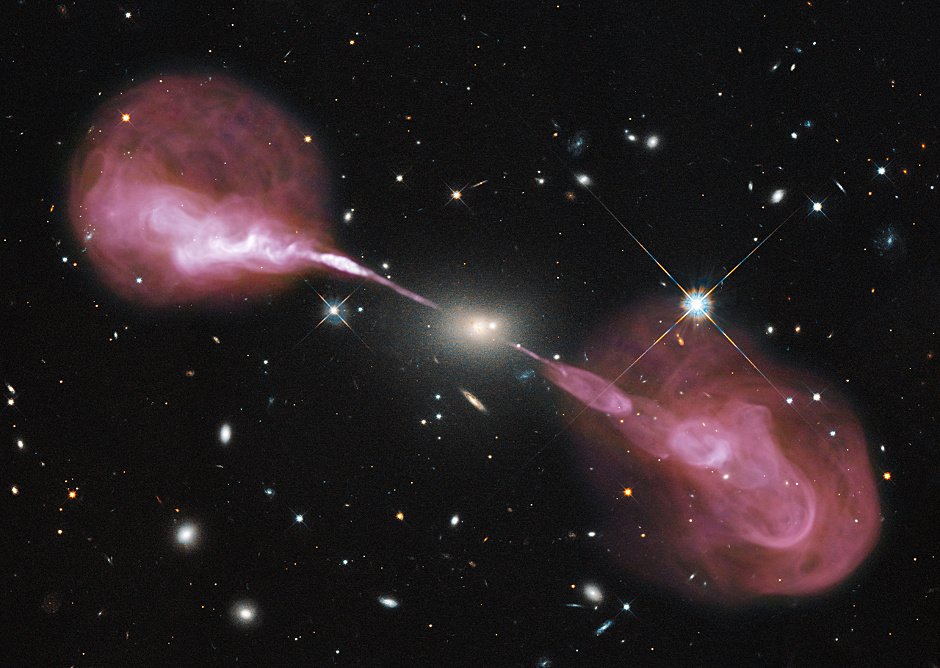

Through the project, volunteers are given telescope images taken in both the radio and infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum and are asked to compare the pictures and match the “radio source” to the galaxy it lives in.

The results from the first year of the Radio Galaxy Zoo project, led by Dr Julie Banfield of the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-Sky Astrophysics and The Australian National University and Dr Ivy Wong from The University of Western Australia, were just published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Oxford University Press.

Before unleashing the eager crowd of online volunteers, the research team tested the same 100 images on both the trained citizen scientists and an expert team of 10 professional astronomers.

“With this early study we’ve comfortably shown that anyone, once we’ve trained them through our tutorial, is as good as our expert panel,” Dr Banfield said.

“The volunteers have already ‘eyeballed’ more than 1.2 million radio images from the Very Large Array in New Mexico, CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array, and infrared images from NASA’s Spitzer and WISE Space Telescopes.”

In one year, the citizen scientists managed to match 60,000 radio sources to their host galaxy — a feat that would have taken a single astronomer working 40 hours a week roughly 50 years to complete.

“In the upcoming all-sky radio surveys, we are expecting 70 million sources — 10 per cent of which will not be classifiable by any of the computer algorithms currently available,” Dr Wong said.

“This 10 per cent will have weird and complex structures that need a human brain to interpret and understand rather than a computer program.

“We have asked our volunteers to identify 170,000 radio sources that are most likely to have unusual structures using current datasets, so we are better prepared for what we could find in the upcoming next generation radio surveys.”

At Radio Galaxy Zoo, professional astronomers talk to the participants every day on a dedicated forum and often ask them to look out for objects of interest.

“One member of the Radio Galaxy Zoo science team in Mexico loves looking for ‘giants’ — jets longer than a megaparsec, or about 125 times the distance from Earth to the centre of the Milky Way. These are typically very, very old radio jets,” Dr Wong said.

Radio Galaxy Zoo is an online project in which citizen scientists are helping professionals identify galaxies hosting jet-emitting massive black holes. See radio.galaxyzoo.org for more information, including information on volunteering.