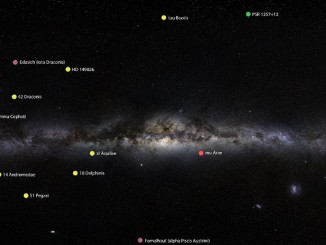

“The volunteers started chatting about the yellow balls they kept seeing in the images of our galaxy, and this brought the features to our attention,” said Grace Wolf-Chase of the Adler Planetarium in Chicago. A colourful, 122-foot (37-metre) Spitzer mosaic of the Milky Way hangs at the planetarium, showcasing our galaxy’s bubbling brew of stars. The yellow balls in this mosaic appear small but are actually several hundred to thousands of times the size of our Solar System.

“With prompting by the volunteers, we analysed the yellow balls and figured out that they are a new way to detect the early stages of massive star formation,” said Charles Kerton of Iowa State University, Ames. “The simple question of ‘Hmm, what’s that?’ led us to this discovery.” Kerton is lead author, and Wolf-Chase a co-author, of a new study on the findings in the Astrophysical Journal.

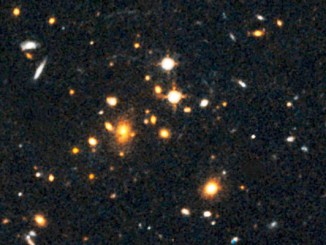

The Milky Way Project is one of many so-called citizen scientist projects making up the Zooniverse website, which relies on crowdsourcing to help process scientific data. So far, more than 70 scientific papers have resulted from volunteers using Zooniverse, four of which are tied to the Milky Way Project. In 2009, volunteers using a Zooniverse project called Galaxy Zoo began chatting about unusual objects they dubbed “green peas.” Their efforts led to the discovery of a class of compact galaxies that churned out extreme numbers of stars.

Volunteers have classified more than 5,000 of these green bubbles using the project’s Web-based tools. When they started reporting that they were finding more reoccurring features in the shape of yellow balls, the Spitzer researchers took note and even named the features accordingly. In astronomy and other digital imaging, yellow represents areas where green and red overlap. So what are these yellow balls?

A thorough analysis by the team led to the conclusion that the yellow balls precede the green bubble features, representing a phase of star formation that takes place before the bubbles form.

“The yellow balls are a missing link,” said Wolf-Chase, “between the very young embryonic stars buried in dark filaments and newborn stars blowing the bubbles.”

“If you wind the clock backwards from the bubbles, you get the yellow ball features,” said Kerton.

The researchers explained why the yellow balls appear yellow: The PAHs, which appear green in the Spitzer images, haven’t been cleared away by the winds from massive stars yet, so the green overlaps with the warm dust, coloured red, to make yellow. The yellow balls are compact because the harsh effects of the massive star have yet to fully expand into their surroundings.

So far, the volunteers have identified more than 900 of these compact yellow features. The next step for the researchers is to look at their distribution. Many appear to be lining the rims of the bubbles, a clue that perhaps the massive stars are triggering the birth of new stars as they blow the bubbles, a phenomenon known as triggered star formation. If the effect is real, the researchers should find that the yellow balls statistically appear more often with bubble walls.

“These results attest to the importance of citizen scientist programs,” said Wolf-Chase. Kerton added, “There is always the potential for serendipitous discovery that makes citizen science both exciting for the participants and useful to the professional astronomer.”