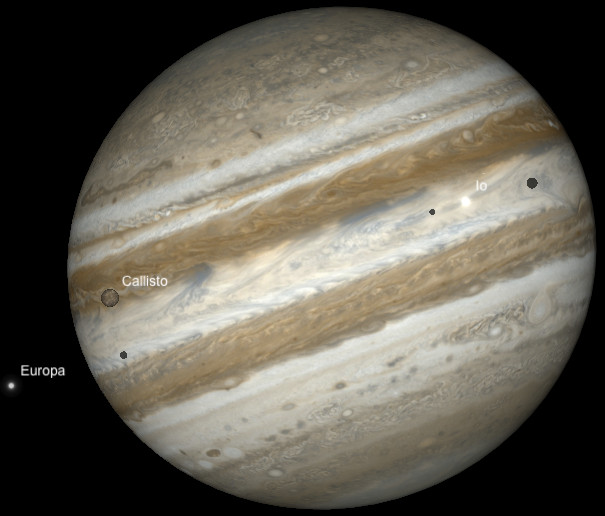

For many observers, however, the fascination with Jupiter lies not in the planet itself, but in its retinue of four bright Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. It so happens that Jupiter’s equator and the orbits of these four big moons are presently almost edge-on to our line of sight — something that only happens twice in the planet’s 11.9-year orbit of the Sun — an alignment that enables us to see the moons regularly eclipse and occult each other.

Eclipses and occultations

The accompanying diagram shows that Io, Europa and Ganymede are locked in a 1:2:4 orbital resonance, meaning that for every orbit of Jupiter that Ganymede makes, Io completes four. Similarly, for every orbit Europa makes, Io completes two. Since the orbital periods of the three moons are approximately 42, 85, and 172 hours, respectively, we can expect that mutual events will occur around multiples of these units. As we will see below, this also applies to shadow transits of the moons on the cloud tops of Jupiter.

Despite their large physical size — Io (diameter 3644 km / 2264 miles), Europa (3122 km / 1940 miles), Ganymede (5268 km / 3273 miles) and Callisto (4820 km / 2995 miles) — the moons will be around 700 million kilometres (430 million miles) from Earth in December. Consequently, their apparent sizes in a high-power eyepiece of even a large telescope will be tiny, just 1 arcsecond for Io and 1.5 arcseconds for Ganymede, so no spacecraft-revealed detail on the surface of these moons will be visible from Earth… or will it?

Planetary imager extraordinaire Damian Peach has imaged albedo features on the Galilean moons on a number of occasions, sometimes from exotic locations. Hopefully, good seeing will also favour UK-based high-resolution planetary imagers for the following events.

For purely visual observers, detecting the tiny discs of the Galilean moons at high magnification will be a challenge, but it will also be interesting to note the rapidly changing aspect of the moons. For occulted moons, see how long you can discern them as separate entities before they coalesce, then time how long it takes to see them as a ‘double star’ again. For eclipsed moons, can you see the shadow falling upon them, or detect any drop in magnitude?

The table below lists the events visible from the UK until the end of the year:

Multiple shadow transits

If you observe Jupiter at just the right time, the Great Red Spot may be on view. Or your eye may be drawn to a tiny, inky-black dot that seems to dissolve away in poor seeing, only to reappear a few seconds later. No, your eyes are not playing tricks — you’re witnessing the shadow of one (or more) of the four Galilean moons slowly drifting across the cloud tops of their parent planet.

A single shadow transit of a Galilean moon is a common occurrence. However, a simultaneous transit of two moons is somewhat rarer, and a triple transit is something you might see one or twice a decade. (Sadly, it’s not possible to see the shadows of all four Galilean moons in simultaneous transit.) Fortunately for us, a number of double transits occur this month. I’ve also included advance notice of a showcase observing target for next month — the triple shadow transit on 24th January 2015!

Our Almanac will give you the start and end times of individual shadow transits, accurate to a couple of minutes. The illustrations that follow are based on computer simulations of the appearance of Jupiter and the configurations of the moon(s) casting the shadow(s), roughly centred on the mid-point of the selected event, or when twilight interferes with observation. Note that the orientation is north up and west to the right; a refractor or catadioptric telescope with a star diagonal will be flipped east-west, while a Newtonian reflector user should invert the images to match their view.

16th December 2014 — 6:40 UT

23rd December 2014 — 8:15 UT

26th December 2014 — 21:30 UT

2nd January 2015 — 23:30 UT

24th January 2015 — 6:40 UT