Everything you need to know to get started with observing meteors.

Click here for a calendar of events over the year.

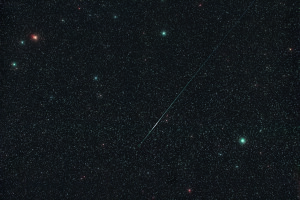

Image: Pawel Zgrzebnick.

What are meteors?

Many people have looked up to see a ‘shooting star’ zipping across the sky. Of course, it is not really a star but a tiny piece of dust called a meteoroid burning up in Earth’s atmosphere. This small chuck of debris can range from a couple of millimetres across to a few centimetres across; something the size of a grain of rice would produce a visually pleasing meteor.

Where do meteors come from?

Icy, dusty comets shed material as they approach the Sun. The heat turns their ice into gas, which is ejected into space, also spewing out tons of dust per second. This material is left in the comet’s orbit and if the Earth’s orbit happens to intersect one of the streams, we see a meteor shower as our planet passes through the debris field. These particles travel at speeds between 11 and 72 km/s and although the air is thin at heights between 30 and 50 miles up, it is still dense enough for the particles to burn up.

What is the difference between a meteor shower and a random meteor shooting across the sky?

Meteors come in two types, sporadic and shower. Gaze up on any clear night and you might see a sporadic ‘shooting star’ coming from any direction. These could be from asteroids, comets or even man-made space debris. Then at regular times each year, Earth encounters a cometary meteoroid stream and we see a shower that appears to originate from a ‘radiant’ point on the sky. The radiant gives the shower its name. For example, the Lyrids appear from the direction of the constellation Lyra.

What do I need to observe meteors?

Warm clothing and patience is all you really need! But to maximise your enjoyment and success, keep these things in mind:

A Moon-free sky: In the perfect situation, the Moon would be out of the sky but if that does not favour you, as long as the Moon is a crescent, meteor observations can be made.

Dark skies: Trying to observe a meteor shower in a heavily light polluted area will have the same effect as observing with a bright Moon overhead, pretty pointless. If you can get to a dark location you will see a far greater number of meteors.

Eyes only: You will need nothing more than your eyes; binoculars and telescopes are too powerful because they narrow down the amount of sky you can see. Your eyes can take in a far greater amount of sky, allowing you to see more meteors.

Don’t look at the radiant: Meteors appearing closer to the radiant have shorter visible trails because their paths point almost straight at the observer. Meteors seen farther away from the radiant create longer, more dramatic streaks across the sky, making them more impressive to watch. So while the radiant is a useful signpost to get oriented, don’t fixate on it – look at the wide expanse of the whole sky to increase your chance of seeing longer meteor streaks.

Stay warm: Stay warm with suitable clothing and a flask of hot drink. Comfortable seating is also important, try a deck chair or a lounger and a blanket.

Keeping count/sketching: You may consider documenting what you see. Keep a tally of the meteors that appear and perhaps draw any exceptionally bright ones.

When can I observe meteor showers?

There are several meteor showers a year. The Perseids in August arguably provides the best meteor shower of the year, but autumn and winter in the northern hemisphere brings four good showers, especially the Geminids, between October and late December. Click here for a full calendar.

Above all, enjoy the wonders of the Solar System’s very own fireworks display and perhaps make a wish upon a shooting star.

Based on an article by Neil Norman, featured in the November issue of Astronomy Now. Neil Norman runs the Facebook group CometWatch.