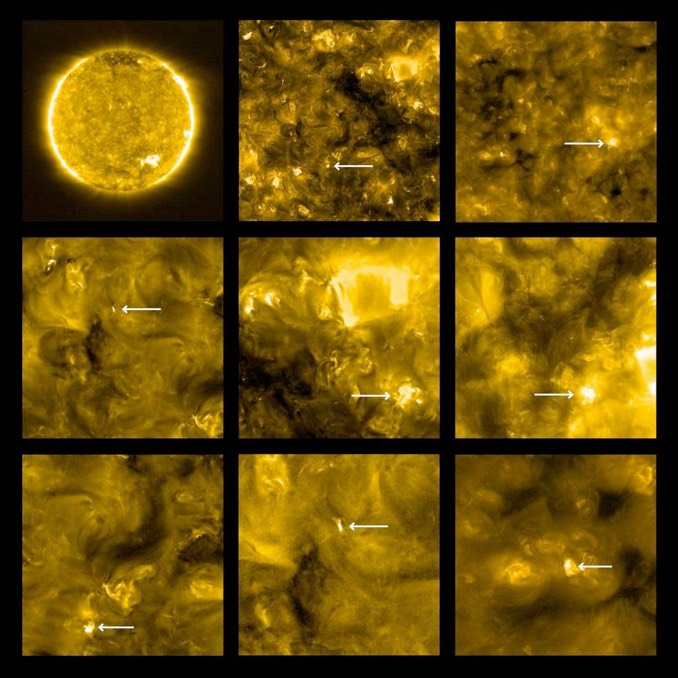

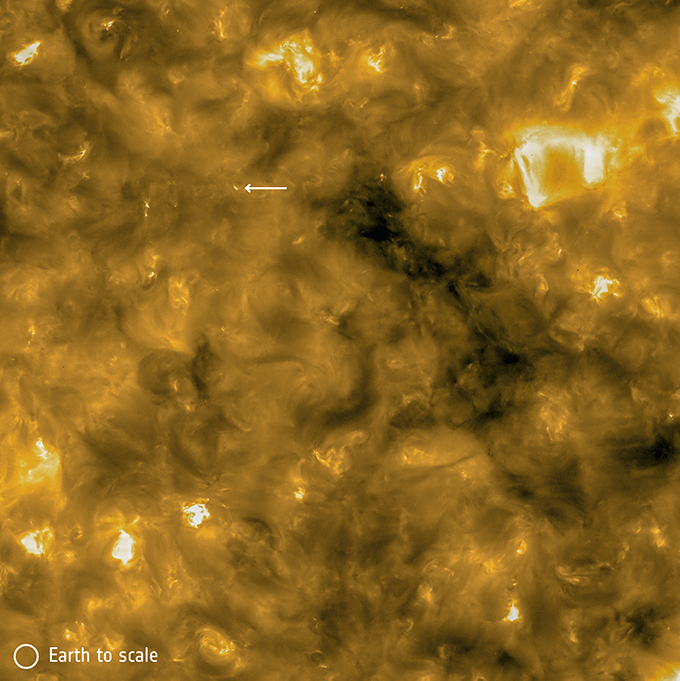

The ESA/NASA Solar Orbiter’s first images, unveiled 16 July, provide a spectacular new look at the Sun, including surprising views of small flare-like blazes dubbed “campfires” that may provide at least some of the energy powering the star’s million-degree corona.

Daniel Müller, Solar Orbiter project scientist with the European Space Agency, said it’s too early to draw conclusions but “there is the possibility that what we see here … could contribute significantly” to heating the Sun’s outer atmosphere.

The American physicist Eugene Parker theorised in 1987 that a sea of small, magnetically powered “nanoflares” could be the mechanism that heats up the corona to such high temperatures.

While the new data do not yet resolve the issue, “our conjecture is these campfires … are related to changes in the Sun’s magnetic field, a process known as magnetic reconnection,” Müller said during a news briefing. “We believe that even though it’s the ‘quiet’ Sun, and there are only small scale magnetic fields, these filaments do get tangled and get under stress. And like rubber bands, they can eventually tear and then reconfigure into new configurations.”

“That tearing process can release energy, vast quantities, and that would then heat the plasma locally to temperatures of more than a million degrees, which is what we see.”

Along with the campfire images, ESA also released full-disc photos and data from the spacecraft’s other instruments, captured at a distance of about 77 million kilometres (48 million miles) from the Sun, showing an extraordinary level of detail.

“We’ve never been closer to the sun with a camera, and this is just the beginning of the long, epic journey of the Solar Orbiter, which will take us even closer to the Sun in less than two years time,” said Müller. “Our closest approach will be just over a quarter of the distance between the Sun and Earth.”

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, named after the man who first suggested the solar wind and nanoflares, flies much closer to the Sun, periodically passing through the outer regions of the corona. But in doing so, it has to endure temperatures that are too high for sun-facing cameras.

“Parker Solar probe is going closer to the Sun, much closer, within nine solar radii,” said Holly Gilbert, Solar Orbiter project scientist for NASA. “But the environment that close is extremely harsh. They have one camera that’s not facing the Sun, it’s facing away so it can watch the solar wind. So Solar Orbiter is (at) the limit of where cameras can take images of the Sun itself.”