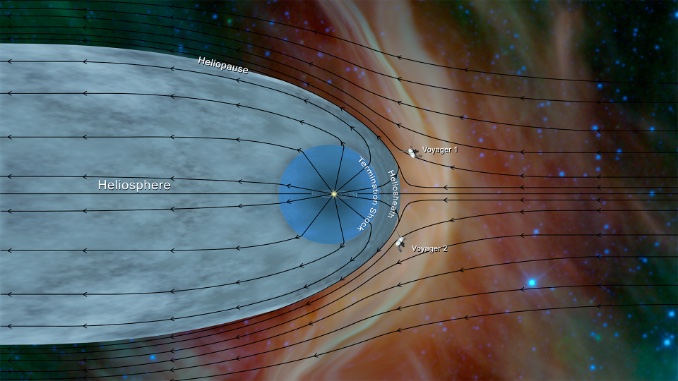

One year ago, on Nov. 5, 2018, NASA’s Voyager 2 became only the second spacecraft in history to leave the heliosphere – the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields created by our Sun. At a distance of about 11 billion miles (18 billion kilometres) from Earth – well beyond the orbit of Pluto – Voyager 2 had entered interstellar space, or the region between stars. On 4 November, five new research papers in the journal Nature Astronomy describe what scientists observed during and since Voyager 2’s historic crossing.

Each paper details the findings from one of Voyager 2’s five operating science instruments: a magnetic field sensor, two instruments to detect energetic particles in different energy ranges and two instruments for studying plasma (a gas composed of charged particles). Taken together, the findings help paint a picture of this cosmic shoreline, where the environment created by our Sun ends and the vast ocean of interstellar space begins.

The Sun’s heliosphere is like a ship sailing through interstellar space. Both the heliosphere and interstellar space are filled with plasma, a gas that has had some of its atoms stripped of their electrons. The plasma inside the heliosphere is hot and sparse, while the plasma in interstellar space is colder and denser. The space between stars also contains cosmic rays, or particles accelerated by exploding stars. Voyager 1 discovered that the heliosphere protects Earth and the other planets from more than 70% of that radiation.

When Voyager 2 exited the heliosphere last year, scientists announced that its two energetic particle detectors noticed dramatic changes: The rate of heliospheric particles detected by the instruments plummeted, while the rate of cosmic rays (which typically have higher energies than the heliospheric particles) increased dramatically and remained high. The changes confirmed that the probe had entered a new region of space.

Before Voyager 1 reached the edge of the heliosphere in 2012, scientists didn’t know exactly how far this boundary was from the Sun. The two probes exited the heliosphere at different locations and also at different times in the constantly repeating, approximately 11-year solar cycle, over the course of which the Sun goes through a period of high and low activity. Scientists expected that the edge of the heliosphere, called the heliopause, can move as the Sun’s activity changes, sort of like a lung expanding and contracting with breath. This was consistent with the fact that the two probes encountered the heliopause at different distances from the Sun.

The new papers now confirm that Voyager 2 is not yet in undisturbed interstellar space: Like its twin, Voyager 1, Voyager 2 appears to be in a perturbed transitional region just beyond the heliosphere.

“The Voyager probes are showing us how our Sun interacts with the stuff that fills most of the space between stars in the Milky Way galaxy,” said Ed Stone, project scientist for Voyager and a professor of physics at Caltech. “Without this new data from Voyager 2, we wouldn’t know if what we were seeing with Voyager 1 was characteristic of the entire heliosphere or specific just to the location and time when it crossed.”