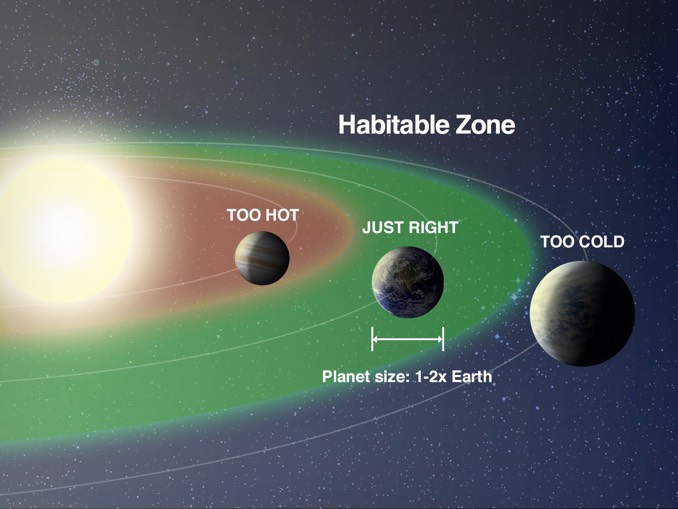

It’s a given that the search for life on other worlds, at least life as it’s known on Earth, should be limited to a star’s habitable zone, the “Goldilocks” region where were temperatures are moderate and water can exist as a liquid. But a new study indicates the zone capable of supporting the development of animals more complex than microbes is actually much more restrictive, making it even tougher for ET to evolve.

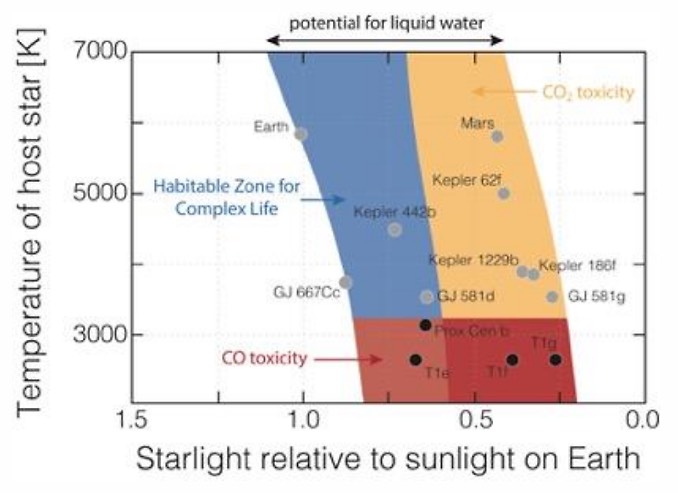

Accounting for the buildup of toxic gases predicted to occur in the atmospheres of most planets narrows the habitable zone for complex life by half and, in some cases, rules it out altogether, the study concludes.

“This is the first time the physiological limits of life on Earth have been considered to predict the distribution of complex life elsewhere in the universe,” said Timothy Lyons, professor of biogeochemistry at the University of California Riverside and co-author of the study in The Astrophysical Journal.

“Imagine a ‘habitable zone for complex life’ defined as a safe zone where it would be plausible to support rich ecosystems like we find on Earth today,” he said. “Our results indicate that complex ecosystems like ours cannot exist in most regions of the habitable zone as traditionally defined.”

Using computer models to simulate a variety of climates and photochemical processes, the researchers found that vast amounts of carbon dioxide would be needed in the outer reaches of a star’s traditional habitable zone to maintain temperatures above freezing – tens of thousands of times more CO2 than found in Earth’s atmosphere today.

The study indicates carbon dioxide alone narrows the habitable zone for simple animals by half. For higher order life forms, the “safe zone” is reduced even more, the researchers found. In addition, planets in the traditional habitable zones of the most common M dwarf stars likely would not be habitable at all by earthly standards thanks to ultraviolet radiation and subsequent formation of carbon monoxide.

That includes Proxima Centauri, the nearest star to Earth, and the TRAPPIST-1 solar system.

While it is not yet possible to detect biosignatures in alien atmospheres, the research provides a guideline of sorts to inform future efforts as the number of confirmed exoplanets grows.

“Our discoveries provide one way to decide which of these myriad planets we should observe in more detail,” said Christopher Reinhard, assistant professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology and co-author of the study. “We could identify otherwise habitable planets with carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide levels that are likely too high to support complex life.”

Said lead author Edward Schwieterman, a NASA postdoctoral fellow: “I think showing how rare and special our planet is only enhances the case for protecting it. As far as we know, Earth is the only planet in the universe that can sustain human life.”