Data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia spacecraft indicate another relatively large galaxy crashed into the Milky Way some 10 billion years ago, merging with Earth’s future home and deeply influencing its development.

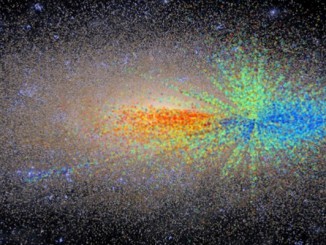

Using ultra-precise 3D position and velocity data collected during Gaia’s first 22 months of observations, a team of astronomers led by Amina Helmi of the University of Groningen in The Netherlands, studied a population of seven million stars and discovered that about 30,000 were part of an “odd collection” spread across the nearby sky.

Even though they are mixed in with other stars, they stand out because they’re all moving along trajectories in the opposite direction of the Sun and vast majority of other stars in the Milky Way. They also belong to a distinct stellar population based on colour and brightness.

“The collection of stars we found with Gaia has all the properties of what you would expect from the debris of a galactic merger,” said Amina, lead author of the paper describing the research in the journal Nature.

Those stars now form most of the Milky Way’s inner halo, older stars born in the distant past that now surround the galaxy’s central bulge and disc. Along with providing the stars in the Milky Way’s halo, the absorbed galaxy also may have thickened up the galactic disc, which contains up to 20 percent of the Milky Way’s stars.

“We became only certain about our interpretation after complementing the Gaia data with additional information about the chemical composition of stars, supplied by the ground-based APOGEE survey,” said Carine Babusiaux of the Université Grenoble Alpes, France, and second author of the paper.

The researchers named the absorbed galaxy Gaia-Enceladus after one of the Giants in ancient Greek mythology. The team identified hundreds of variable stars and 13 globular clusters in the Milky Way that follow trajectories similar to those followed by stars originating in Gaia-Enceladus.

At the time of the collision, the Milky Way would have been about four times larger than Gaia-Enceladus.

“We can now say this is the way the Galaxy formed in those early epochs,” Amina said. “It’s fantastic. It’s just so beautiful and makes you feel so big and so small at the same time.”

Said Gaia project scientist Timo Prusti: “By reading the motions of stars scattered across the sky, we are now able to rewind the history of the Milky Way and discover a major milestone in its formation, and this is possible thanks to Gaia.”