NASA’s Dawn mission is drawing to a close after 11 years of breaking new ground in planetary science, gathering breathtaking imagery, and performing unprecedented feats of spacecraft engineering.

Dawn’s mission was extended several times, outperforming scientists’ expectations in its exploration of two planet-like bodies, Ceres and Vesta, that make up 45 percent of the mass of the main asteroid belt. Now the spacecraft is about to run out of a key fuel, hydrazine. When that happens, most likely between mid-September and mid-October, Dawn will lose its ability to communicate with Earth. It will remain in a silent orbit around Ceres for decades.

“Although it will be sad to see Dawn’s departure from our mission family, we are intensely proud of its many accomplishments,” said Lori Glaze, acting director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Not only did this spacecraft unlock scientific secrets at these two small but significant worlds, it was also the first spacecraft to visit and orbit bodies at two extraterrestrial destinations during its mission. Dawn’s science and engineering achievements will echo throughout history.”

When Dawn launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida in September 2007, strapped on a Delta II-Heavy rocket, scientists and engineers had an idea of what Ceres and Vesta looked like. Thanks to ground- and space-based telescopes, including NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, the bodies in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter were visible — but even the best pictures were fuzzy.

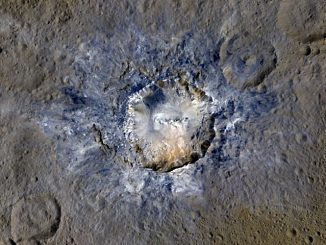

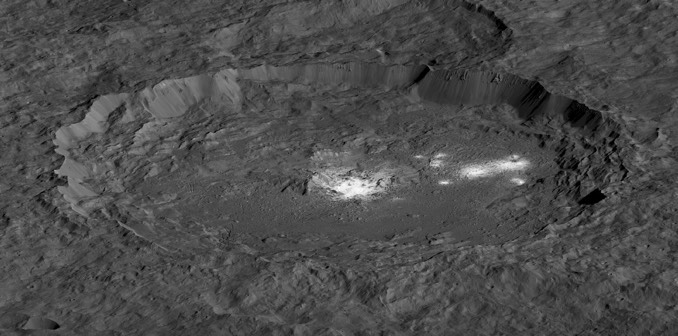

From 2011 to 2012, Dawn swept over Vesta, capturing images that exceeded everyone’s imaginings — craters, canyons and even mountains. Then on Ceres in 2015, Dawn showed us a cryovolcano and mysterious bright spots, which scientists later found might be salt deposits produced by the exposure of briny liquid from Ceres’ interior. Through Dawn’s eyes, these bright spots were especially stunning, glowing like diamonds scattered across the dwarf planet’s surface.

“Dawn’s legacy is that it explored two of the last uncharted worlds in the inner Solar System,” said Marc Rayman of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena California, who serves as Dawn’s mission director and chief engineer. “Dawn has shown us alien worlds that for two centuries were just pinpoints of light amidst the stars. And it has produced these richly detailed, intimate portraits and revealed exotic, mysterious landscapes unlike anything we’ve ever seen.”

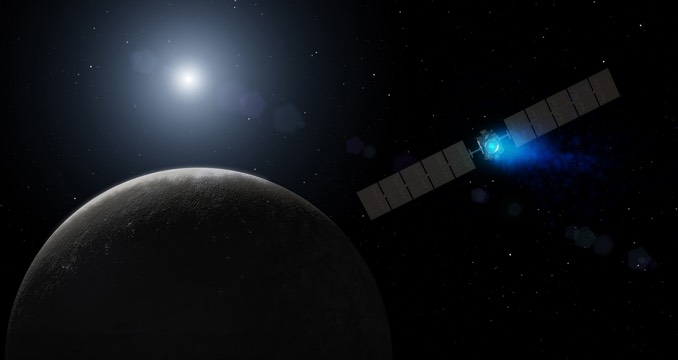

Dawn is the only spacecraft to orbit a body in the asteroid belt. And it is the only spacecraft to orbit two extraterrestrial destinations. These feats were possible thanks to ion propulsion, a tremendously efficient propulsion system familiar to science-fiction fans and space enthusiasts. Dawn pushed the limits of the system’s capabilities and stamina, showing how useful it is for other missions that aim to visit multiple destinations.

Pushed by ion propulsion, Dawn reached Vesta in 2011 and investigated it from surface to core during 14 months in orbit. In 2012, engineers manoeuvred Dawn out of orbit and steered it though the asteroid belt for more than two years before inserting it into orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres, where it has been collecting data since 2015.

“Vesta and Ceres have each told their story of how and where they formed, and how they evolved — a fiery magmatic history that led to rocky Vesta and a cooler, water-rich history that resulted in the ancient ocean world Ceres,” said Carol Raymond of JPL, principal investigator of the Dawn mission. “These treasure troves of information will continue to help us understand other bodies in the Solar System far into the future.

There was so much that scientists didn’t know about Ceres before Dawn arrived. Raymond wondered whether they might find Ceres covered with a smooth, young surface — an enormous cue ball with a frozen crust. Instead, they found the dwarf planet wearing the chemistry of its old ocean. “What we found was completely mind-blowing. Ceres’ history is just splayed all over its surface,” she said.

Some of the dazzling bright spots turned out to be brilliant salty deposits, composed mainly of sodium carbonate that made its way to the surface in a slushy brine from within or below the crust.

The findings reinforce the idea that dwarf planets, not just icy moons like Enceladus and Europa, could have hosted oceans during their history — and potentially still do. Analyses from Dawn data suggest there may still be liquid under Ceres’ surface and that some regions were geologically active relatively recently, feeding from a deep reservoir.

One of Dawn’s biggest reveals on Ceres lay in the region of Ernutet Crater. Organic molecules were found in abundance. Organics are among the building blocks of life, though Dawn’s data can’t determine if Ceres’ organics were formed by biological processes.

“There is growing evidence that the organics in Ernutet came from Ceres’ interior, in which case they could have existed for some time in the early interior ocean,” said Julie Castillo-Rogez, Dawn’s project scientist and deputy principal investigator at JPL.

Because Ceres has conditions of interest to scientists who study chemistry that leads to the development of life, NASA follows strict planetary protection protocols for the disposal of the Dawn spacecraft. Unlike Cassini, which deliberately plunged into Saturn’s atmosphere to protect the system from contamination — Dawn will remain in orbit around Ceres, which has no atmosphere.

Engineers designed Dawn’s final orbit to ensure it will not crash for at least 20 years — and likely decades longer.

Rayman, who led the team that flew Dawn throughout the mission and into its final orbit, likes to think of Dawn’s end this way: as “an inert, celestial monument to human creativity and ingenuity.”