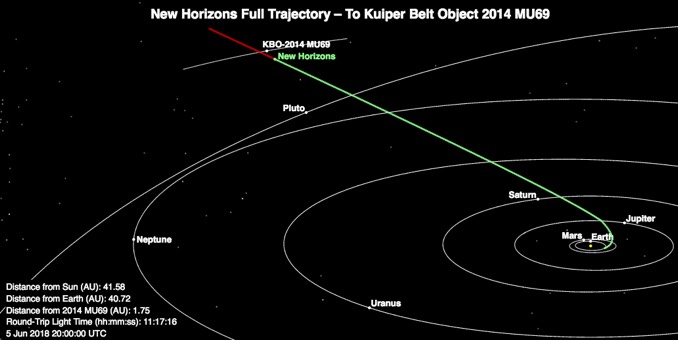

Three years after racing past Pluto and on into the Kuiper Belt, NASA’s New Horizons probe woke itself up from six months of electronic hibernation 5 June, phoning home to let flight controllers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory know it was in good health and on course for a New Year’s day flyby of its second and final target.

Alice Bowman, mission operations manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, said controllers had no reason to doubt an on-time wakeup but the team was thrilled nonetheless to see telemetry start flowing in. The spacecraft actually woke up the night before, but at 3.8 billion miles from Earth, it took the confirming telemetry five hours and 40 minutes to cross the fast gulf.

“We were here in the mission operations center, and it was great,” Bowman said. “We didn’t have to do any reboots, any reconfigurations of the ground systems or anything like that. It went very smooth, and we were very happy.”

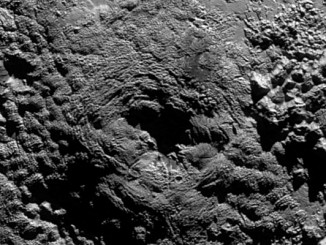

New Horizons, launched in January 2006, flew past Pluto on 14 July, 2015, beaming back dozens of spectacular photos and an enormous trove of data about the famously demoted dwarf planet and its large moon Charon.

Pluto is the most famous member of the Kuiper Belt, a vast realm of rocky debris in the outer reaches of the solar system that includes an unknown number of dwarf planets and billions of smaller bodies left over from the birth of the solar system 4.5 billion years ago.

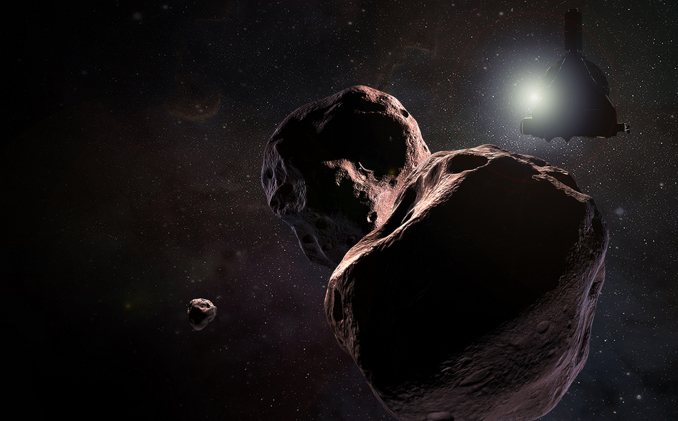

One of those bodies, known as 2104 MU69, was close enough to New Horizons’ trajectory for the spacecraft to reach with its remaining propellant. Spotted during a search for possible targets by the Hubble Space Telescope, 2104 MU69 later was nicknamed Ultima Thule by the science team with input from the public.

After sending back the data collected during the Pluto flyby, and after a rocket firing to put the craft on course for a 1 January flyby of Ultima Thule, New Horizons was commanded to go to sleep last 21 December, giving mission planners uninterrupted time to map out the Ultima encounter.

At wakeup Tuesday, New Horizons was about 262 million kilometres (162 million miles) from its target and moving at nearly 51,000 kph (31,600 mph). Because flight controllers are not yet sure about what might lurk in the environment near Ultima, two flyby scenarios have been developed.

“The primary flyby distance is 3,500 kilometres (2,100 miles),” Bowman said. “If we see something on approach that causes us pause and we want to move farther away, we have an alternate set of commands that will take us to about 10,000 kilometres (6,200 miles) distance. So we have two of those going on.”

New Horizons flew past Pluto at a distance of about 7,800 miles. Passing Passing nearly four times closer to Ultima, the spacecraft’s main camera should be able to resolve surface features as small as a basketball, Bowman said.

Over the next two months, New Horizons will keep its main antenna pointed toward Earth, slowly spinning for stability, while flight controllers uplink commands, navigation instruction files and pre-planned science sequences.

If all goes well, science operations will commence 13 August and New Horizons will resume actively navigating toward Ultima. The nine-day flyby sequence will begin Christmas Day with close approach on Jan. 1.